Ruby Hacking Guide

Introduction

Characteristics of Ruby

Some of the readers may have already been familiar with Ruby, but (I hope) there are also many readers who have not. First let’s go though a rough summary of the characteristics of Ruby for such people.

Hereafter capital “Ruby” refers to Ruby as a language specification, and lowercase

“ruby” refers to ruby command as an implementation.

Development style

Ruby is a language that is being developed by the hand of Yukihiro Matsumoto as

an individual. Unlike C or Java or Scheme, it does not have any standard.

The specification is merely

shown as an implementation as ruby, and its varying continuously.

For good or bad, it’s free.

Furthermore ruby itself is a free software.

It’s probably necessary to mention at least the two points here:

The source code is open in public and distributed free of charge.

Thanks to such condition, an attempt like this book can be approved.

If you’d like to know the exact licence, you can read README and LEGAL.

For the time being, I’d like you to remember that you can do at least the

following things:

- You can redistribute source code of

ruby - You can modify source code of

ruby - You can redistribute a copy of source code with your modification

There is no need for special permission and payment in all these cases.

By the way, the purpose of this book is to read the original ruby,

thus the target source is the one not modified unless it is particularly

specified. However, white spaces, new lines and comments were added or removed

without asking.

It’s conservative

Ruby is a very conservative language. It is equipped with only carefully chosen features that have been tested and washed out in a variety of languages. Therefore it doesn’t have plenty of fresh and experimental features very much. So it has a tendency to appeal to programmers who put importance on practical functionalities. The dyed-in-the-wool hackers like Scheme and Haskell lovers don’t seem to find appeal in ruby, at least in a short glance.

The library is conservative in the same way. Clear and unabbreviated names are

given for new functions, while names that appears in C and Perl libraries have

been taken from them. For example, printf, getpwent, sub, and tr.

It is also conservative in implementation. Assembler is not its option for seeking speed. Portability is always considered a higher priority when it conflicts with speed.

It is an object-oriented language

Ruby is an object-oriented language. It is absolutely impossible to exclude it from the features of Ruby.

I will not give a page to this book about what an object-oriented language is. To tell about an object-oriented feature about Ruby, the expression of the code that just going to be explained is the exact sample.

It is a script language

Ruby is a script language. It seems also absolutely impossible to exclude this from the features of Ruby. To gain agreement of everyone, an introduction of Ruby must include “object-oriented” and “script language”.

However, what is a “script language” for example? I couldn’t figure out the

definition successfully. For example, John K. Ousterhout, the author of Tcl/Tk,

gives a definition as “executable language using #! on UNIX”. There are other

definitions depending on the view points, such as one that can express a useful

program with only one line, or that can execute the code by passing a program

file from the command line, etc.

However, I dare to use another definition, because I don’t find much interest in “what” a script language. I have the only one measure to decide to call it a script language, that is, whether no one would complain about calling it a script language. To fulfill this definition, I would define the meaning of “script language” as follows.

A language that its author calls it a “script language”.

I’m sure this definition will have no failure. And Ruby fulfills this point. Therefore I call Ruby a “script language”.

It’s an interpreter

ruby is an interpreter. That’s the fact. But why it’s an interpreter? For

example, couldn’t it be made as a compiler?

It must be because in some points being an interpreter is better than being

a compiler … at least for ruby, it must be better.

Well, what is good about being an interpreter?

As a preparation step to investigating into it, let’s start by thinking about the difference between an interpreter and a compiler. If the matter is to attempt a theoretical comparison in the process how a program is executed, there’s no difference between an interpreter language and a compile language. Because it works by letting CPU interpret the code compiled to the machine language, it may be possible to say it works as an interpreter. Then where is the place that actually makes a difference? It is a more practical place, in the process of development.

I know somebody, as soon as hearing “in the process of development”, would claim using a stereotypical phrase, that an interpreter reduces effort of compilation that makes the development procedure easier. But I don’t think it’s accurate. A language could possibly be planned so that it won’t show the process of compilation. Actually, Delphi can compile a project by hitting just F5. A claim about a long time for compilation is derived from the size of the project or optimization of the codes. Compilation itself doesn’t owe a negative side.

Well, why people perceive an interpreter and compiler so much different like this? I think that it is because the language developers so far have chosen either implementation based on the trait of each language. In other words, if it is a language for a comparatively small purpose such as a daily routine, it would be an interpreter. If it is for a large project where a number of people are involved in the development and accuracy is required, it would be a compiler. That may be because of the speed, as well as the ease of creating a language.

Therefore, I think “it’s handy because it’s an interpreter” is an outsized myth. Being an interpreter doesn’t necessarily contribute the readiness in usage; seeking readiness in usage naturally makes your path toward building an interpreter language.

Anyway, ruby is an interpreter; it has an important fact about where this

book is facing, so I emphasize it here again.

Though I don’t know about “it’s handy because it is an interpreter”,

anyway ruby is implemented as an interpreter.

High portability

Even with a problem that fundamentally the interfaces are Unix-centered, I

would insist ruby possesses a high portability.

It doesn’t require any extremely unfamiliar library.

It has only a few parts written in assembler.

Therefore porting to a new platform is comparatively easy. Namely, it works

on the following platforms currently.

- Linux

- Win32 (Windows 95, 98, Me, NT, 2000, XP)

- Cygwin

- djgpp

- FreeBSD

- NetBSD

- OpenBSD

- BSD/OS

- Mac OS X

- Solaris

- Tru64 UNIX

- HP-UX

- AIX

- VMS

- UX/4800

- BeOS

- OS/2 (emx)

- Psion

I heard that the main machine of the author Matsumoto is Linux. Thus when using Linux, you will not fail to compile any time.

Furthermore, you can expect a stable functionality on a (typical) Unix environment.

Considering the release cycle of packages, the primary option

for the environment to hit around ruby should fall on a branch of PC UNIX,

currently.

On the other hand, the Win32 environment tends to cause problems definitely. The large gaps in the targeting OS model tend to cause problems around the machine stack and the linker. Yet, recently Windows hackers have contributed to make better support. I use a native ruby on Windows 2000 and Me. Once it gets successfully run, it doesn’t seem to show special concerns like frequent crashing. The main problems on Windows may be the gaps in the specifications.

Another type of OS that many people may be interested in should probably be Mac OS (prior to v9) and handheld OS like Palm.

Around ruby 1.2 and before, it supported legacy Mac OS, but the development

seems to be in suspension. Even a compiling can’t get through. The biggest

cause is that the compiler environment of legacy Mac OS and the decrease of

developers. Talking about Mac OS X, there’s no worries because the body is

UNIX.

There seem to be discussions the portability to Palm several branches, but I

have never heard of a successful project. I guess the difficulty lies in the

necessity of settling down the specification-level standards such as stdio on

the Palm platform, rather than the processes of actual implementation. Well I

saw a porting to Psion has been done. ([ruby-list:36028]).

How about hot stories about VM seen in Java and .NET? Because I’d like to talk about them combining together with the implementation, this topic will be in the final chapter.

Automatic memory control

Functionally it’s called GC, or Garbage Collection. Saying it in C-language,

this feature allows you to skip free() after malloc(). Unused memory is

detected by the system automatically, and will be released. It’s so convenient

that once you get used to GC you won’t be willing to do such manual

memory control again.

The topics about GC have been common because of its popularity in recent languages with GC as a standard set, and it is fun that its algorithms can still be improved further.

Typeless variables

The variables in Ruby don’t have types. The reason is probably typeless variables conforms more with polymorphism, which is one of the strongest advantages of an object-oriented language. Of course a language with variable type has a way to deal with polymorphism. What I mean here is a typeless variables have better conformance.

The level of “better conformance” in this case refers to synonyms like “handy”. It’s sometimes corresponds to crucial importance, sometimes it doesn’t matter practically. Yet, this is certainly an appealing point if a language seeks for “handy and easy”, and Ruby does.

Most of syntactic elements are expressions

This topic is probably difficult to understand instantly without a little supplemental explanation. For example, the following C-language program results in a syntactic error.

result = if (cond) { process(val); } else { 0; }

Because the C-language syntax defines if as a statement.

But you can write it as follows.

result = cond ? process(val) : 0;

This rewrite is possible because the conditional operator (a?b:c) is defined

as an expression.

On the other hand, in Ruby, you can write as follows because if is an expression.

result = if cond then process(val) else nil end

Roughly speaking, if it can be an argument of a function or a method, you can consider it as an expression.

Of course, there are other languages whose syntactic elements are mostly expressions. Lisp is the best example. Because of the characteristic around this, there seems many people who feel like “Ruby is similar to Lisp”.

Iterators

Ruby has iterators. What is an iterator? Before getting into iterators, I should mention the necessity of using an alternative term, because the word “iterator” is disliked recently. However, I don’t have a good alternative. So let us keep calling it “iterator” for the time being.

Well again, what is an iterator? If you know higher-order function,

for the time being, you can regard it as something similar to it.

In C-language, the counterpart would be passing a function pointer as an argument.

In C++, it would be a method to which the operation part of STL’s Iterator is enclosed.

If you know sh or Perl,

it’s good to imagine something like a custom for statement which we can define.

Yet, the above are merely examples of “similar” concepts. All of them are similar, but they are not identical to Ruby’s iterator. I will expand the precise story when it’s a good time later.

Written in C-language

Being written in C-language is not notable these days, but it’s still a characteristic for sure. At least it is not written in Haskell or PL/I, thus there’s the high possibility that the ordinary people can read it. (Whether it is truly so, I’d like you confirm it by yourself.)

Well, I just said it’s in C-language, but the actual language version which ruby is targeting is basically K&R C. Until a little while ago, there were a decent number of – not plenty though – K&R-only-environment. But recently, there are a few environments which do not accept programs written in ANSI C, technically there’s no problem to move on to ANSI C. However, also because of the author Matsumoto’s personal preference, it is still written in K&R style.

For this reason, the function definition is all in K&R style, and the prototype

declarations are not so seriously written.

If you carelessly specify -Wall option of gcc,

there would be plenty of warnings shown.

If you try to compile it with a C++ compiler,

it would warn prototype mismatch and could not compile.

… These kind of stories are often reported to the mailing list.

Extension library

We can write a Ruby library in C and load it at runtime without recompiling Ruby. This type of library is called “Ruby extension library” or just “Extension library”.

Not only the fact that we can write it in C, but the very small difference in the code expression between Ruby-level and C-level is also a significant trait. As for the operations available in Ruby, we can also use them in C in the almost same way. See the following example.

# Method call

obj.method(arg) # Ruby

rb_funcall(obj, rb_intern("method"), 1, arg); # C

# Block call

yield arg # Ruby

rb_yield(arg); # C

# Raising exception

raise ArgumentError, 'wrong number of arguments' # Ruby

rb_raise(rb_eArgError, "wrong number of arguments"); # C

# Generating an object

arr = Array.new # Ruby

VALUE arr = rb_ary_new(); # C

It’s good because it provides easiness in composing an extension library, and actually

it makes an indispensable prominence of ruby. However, it’s also a burden for ruby

implementation. You can see the affects of it in many places. The affects to GC and

thread-processing is eminent.

Thread

Ruby is equipped with thread. Assuming a very few people knowing none about thread these days, I will omit an explanation about the thread itself. I will start a story in detail.

`ruby`’s thread is a user-level thread that is originally written. The characteristic of

this implementation is a very high portability in both specification and implementation.

Surprisingly a MS-DOS can run the thread. Furthermore, you can expect the same response

in any environment. Many people mention that this point is the best feature of ruby.

However, as a trade off for such an extremeness of portability, ruby abandons the speed.

It’s, say, probably the slowest of all user-level thread implementations in this world.

The tendency of ruby implementation may be seen here the most clearly.

Technique to read source code

Well. After an introduction of ruby, we are about to start reading source code. But wait.

Any programmer has to read a source code somewhere, but I guess there are not many occasions that someone teaches you the concrete ways how to read. Why? Does it mean you can naturally read a program if you can write a program?

But I can’t think reading the program written by other people is so easy.

In the same way as writing programs, there must be techniques and theories in reading programs.

And they are necessary. Therefore, before starting to ready ruby, I’d like to expand a general

summary of an approach you need to take in reading a source code.

Principles

At first, I mention the principle.

Decide a goal

An important key to reading the source code is to set a concrete goal.

This is a word by the author of Ruby, Matsumoto. Indeed, his word is very convincing for me. When the motivation is a spontaneous idea “Maybe I should read a kernel, at least…”, you would get source code expanded or explanatory books ready on the desk. But not knowing what to do, the studies are to be left untouched. Haven’t you? On the other hand, when you have in mind “I’m sure there is a bug somewhere in this tool. I need to quickly fix it and make it work. Otherwise I will not be able to make the deadline…”, you will probably be able to fix the code in a blink, even if it’s written by someone else. Haven’t you?

The difference in these two cases is motivation you have. In order to know something, you at least have to know what you want to know. Therefore, the first step of all is to figure out what you want to know in explicit words.

However, of course this is not all needed to make it your own “technique”. Because “technique” needs to be a common method that anybody can make use of it by following it. In the following section, I will explain how to bring the first step into the landing place where you achieve the goal finally.

Visualising the goal

Now let us suppose that our final goal is set “Understand all about ruby”. This is certainly

considered as “one set goal”, but apparently it will not be useful for reading the source code

actually. It will not be a trigger of any concrete action. Therefore, your first job will be to

drag down the vague goal to the level of a concrete thing.

Then how can we do it? The first way is thinking as if you are the person who wrote the program. You can utilize your knowledge in writing a program, in this case. For example, when you are reading a traditional “structured” programming by somebody, you will analyze it hiring the strategies of structured programming too. That is, you will divide the target into pieces, little by little. If it is something circulating in a event loop such as a GUI program, first roughly browse the event loop then try to find out the role of each event handler. Or, try to investigate the “M” of MVC (Model View Controller) first.

Second, it’s good to be aware of the method to analyze. Everybody might have certain analysis methods, but they are often done relying on experience or intuition. In what way can we read source codes well? Thinking about the way itself and being aware of it are crucially important.

Well, what are such methods like? I will explain it in the next section.

Analysis methods

The methods to read source code can be roughly divided into two; one is a static method and the other is dynamic method. Static method is to read and analyze the source code without running the program. Dynamic method is to watch the actual behavior using tools like a debugger.

It’s better to start studying a program by dynamic analysis. That is because what you can see there is the “fact”. The results from static analysis, due to the fact of not running the program actually, may well be “prediction” to a greater or lesser extent. If you want to know the truth, you should start from watching the fact.

Of course, you don’t know whether the results of dynamic analysis are the fact really. The debugger could run with a bug, or the CPU may not be working properly due to overheat. The conditions of your configuration could be wrong. However, the results of static analysis should at least be closer to the fact than dynamic analysis.

Dynamic analysis

Using the target program

You can’t start without the target program. First of all, you need to know in advance what the program is like, and what are expected behaviors.

Following the behavior using the debugger

If you want to see the paths of code execution and the data structure produced as a result, it’s quicker to look at the result by running the program actually than to emulate the behavior in your brain. In order to do so easily, use the debugger.

I would be more happy if the data structure at runtime can be seen as a picture, but unfortunately we can nearly scarcely find a tool for that purpose (especially few tools are available for free). If it is about a snapshot of the comparatively simpler structure, we might be able to write it out as a text and convert it to a picture by using a tool like graphviz\footnote{graphviz……See doc/graphviz.html in the attached CD-ROM}. But it’s very difficult to find a way for general purpose and real time analysis.

Tracer

You can use the tracer if you want to trace the procedures that code goes through. In case of C-language, there is a tool named ctrace\footnote{ctrace……http://www.vicente.org/ctrace}. For tracing a system call, you can use tools like strace\footnote{strace……http://www.wi.leidenuniv.nl/~wichert/strace/}, truss, and ktrace.

Print everywhere

There is a word “printf debugging”. This method also works for analysis other than debugging. If you are watching the history of one variable, for example, it may be easier to understand to look at the dump of the result of the print statements embed, than to track the variable with a debugger.

Modifying the code and running it

Say for example, in the place where it’s not easy to understand its behavior, just make a small change in some part of the code or a particular parameter and then re-run the program. Naturally it would change the behavior, thus you would be able to infer the meaning of the code from it.

It goes without saying, you should also have an original binary and do the same thing on both of them.

Static analysis

The importance of names

Static analysis is simply source code analysis. And source code analysis is really an analysis of names. File names, function names, variable names, type names, member names — A program is a bunch of names.

This may seem obvious because one of the most powerful tools for creating abstractions in programming is naming, but keeping this in mind will make reading much more efficient.

Also, we’d like to know about coding rules beforehand to some extent.

For example, in C language, extern function often uses prefix to distinguish the type of functions.

And in object-oriented programs, function names sometimes contain the

information about where they belong to in prefixes,

and it becomes valuable information (e.g. rb_str_length).

Reading documents

Sometimes a document describes the internal structure is included.

Especially be careful of a file named HACKING etc.

Reading the directory structure

Looking at in what policy the directories are divided. Grasping the overview such as how the program is structured, and what the parts are.

Reading the file structure

While browsing (the names of) the functions, also looking at the policy of how the files are divided. You should pay attention to the file names because they are like comments whose lifetime is very long.

Additionally, if a file contains some modules in it, for each module the functions to compose it should be grouped together, so you can find out the module structure from the order of the functions.

Investigating abbreviations

As you encounter ambiguous abbreviations, make a list of them and investigate each of them as early as possible. For example, when it is written “GC”, things will be very different depending on whether it means “Garbage Collection” or “Graphic Context”.

Abbreviations for a program are generally made by the methods like taking the initial letters or dropping the vowels. Especially, popular abbreviations in the fields of the target program are used unconditionally, thus you should be familiar with them at an early stage.

Understanding data structure

If you find both data and code, you should first investigate the data structure.

In other words, when exploring code in C, it’s better to start with header files.

And in this case, let’s make the most of our imagination from their filenames.

For example, if you find frame.h, it would probably be the stack frame definition.

Also, you can understand many things from the member names of a struct and their types.

For example, if you find the member next, which points to its own type, then it

will be a linked list. Similarly, when you find members such as parent, children,

and sibling, then it must be a tree structure. When prev, it will be a stack.

Understanding the calling relationship between functions

After names, the next most important thing to understand is the relationships between functions. A tool to visualize the calling relationships is especially called a “call graph”, and this is very useful. For this, we’d like to utilize tools.

A text-based tool is sufficient,

but it’s even better if a tool can generate diagrams.

However such tool is seldom available (especially few tools are for free).

When I analyzed ruby to write this book,

I wrote a small command language and a parser in Ruby and

generated diagrams half-automatically by passing the results to the tool named graphviz.

Reading functions

Reading how it works to be able to explain things done by the function concisely. It’s good to read it part by part as looking at the figure of the function relationships.

What is important when reading functions is not “what to read” but “what not to read”. The ease of reading is decided by how much we can cut out the codes. What should exactly be cut out? It is hard to understand without seeing the actual example, thus it will be explained in the main part.

Additionally, when you don’t like its coding style,

you can convert it by using the tool like indent.

Experimenting by modifying it as you like

It’s a mystery of human body, when something is done using a lot of parts of your body, it can easily persist in your memory. I think the reason why not a few people prefer using manuscript papers to a keyboard is not only they are just nostalgic but such fact is also related.

Therefore, because merely reading on a monitor is very ineffective to remember with our bodies, rewrite it while reading. This way often helps our bodies get used to the code relatively soon. If there are names or code you don’t like, rewrite them. If there’s a cryptic abbreviation, substitute it so that it would be no longer abbreviated.

However, it goes without saying but you should also keep the original source aside and check the original one when you think it does not make sense along the way. Otherwise, you would be wondering for hours because of a simple your own mistake. And since the purpose of rewriting is getting used to and not rewriting itself, please be careful not to be enthusiastic very much.

Reading the history

A program often comes with a document which is about the history of changes.

For example, if it is a software of GNU, there’s always a file named

ChangeLog. This is the best resource to know about “the reason why the

program is as it is”.

Alternatively, when a version control system like CVS or SCCS is used and you

can access it, its utility value is higher than ChangeLog.

Taking CVS as an example, cvs annotate, which displays the place which

modified a particular line, and cvs diff, which takes difference from the

specified version, and so on are convenient.

Moreover, in the case when there’s a mailing list or a news group for developers, you should get the archives so that you can search over them any time because often there’s the information about the exact reason of a certain change. Of course, if you can search online, it’s also sufficient.

The tools for static analysis

Since various tools are available for various purposes,

I can’t describe them as a whole.

But if I have to choose only one of them, I’d recommend global.

The most attractive point is that its structure allows us to easily use it for

the other purposes. For instance, gctags, which comes with it, is actually a

tool to create tag files, but you can use it to create a list of the function

names contained in a file.

~/src/ruby % gctags class.c | awk '{print $1}'

SPECIAL_SINGLETON

SPECIAL_SINGLETON

clone_method

include_class_new

ins_methods_i

ins_methods_priv_i

ins_methods_prot_i

method_list

:

:

That said, but this is just a recommendation of this author, you as a reader can use whichever tool you like. But in that case, you should choose a tool equipped with at least the following features.

- list up the function names contained in a file

- find the location from a function name or a variable name (It’s more preferable if you can jump to the location)

- function cross-reference

Build

Target version

The version of ruby described in this book is 1.7 (2002-09-12).

Regarding ruby,

it is a stable version if its minor version is an even number,

and it is a developing version if it is an odd number.

Hence, 1.7 is a developing version.

Moreover, 9/12 does not indicate any particular period,

thus this version is not distributed as an official package.

Therefore, in order to get this version,

you can get from the CD-ROM attached to this book or the support site

\footnote{The support site of this book……http://i.loveruby.net/ja/rhg/}

or you need to use the CVS which will be described later.

There are some reasons why it is not 1.6, which is the stable version, but 1.7. One thing is that, because both the specification and the implementation are organized, 1.7 is easier to deal with. Secondly, it’s easier to use CVS if it is the edge of the developing version. Additionally, it is likely that 1.8, which is the next stable version, will be out in the near future. And the last one is, investigating the edge would make our mood more pleasant.

Getting the source code

The archive of the target version is included in the attached CD-ROM. In the top directory of the CD-ROM,

ruby-rhg.tar.gz ruby-rhg.zip ruby-rhg.lzh

these three versions are placed,

so I’d like you to use whichever one that is convenient for you.

Of course, whichever one you choose, the content is the same.

For example, the archive of tar.gz can be extracted as follows.

~/src % mount /mnt/cdrom ~/src % gzip -dc /mnt/cdrom/ruby-rhg.tar.gz | tar xf - ~/src % umount /mnt/cdrom

Compiling

Just by looking at the source code, you can “read” it. But in order to know about the program, you need to actually use it, remodel it and experiment with it. When experimenting, there’s no meaning if you didn’t use the same version you are looking at, thus naturally you’d need to compile it by yourself.

Therefore, from now on, I’ll explain how to compile. First, let’s start with the case of Unix-like OS. There’s several things to consider on Windows, so it will be described in the next section altogether. However, Cygwin is on Windows but almost Unix, thus I’d like you to read this section for it.

Building on a Unix-like OS

When it is a Unix-like OS, because generally it is equipped with a C

compiler, by following the below procedures, it can pass in most cases.

Let us suppose ~/src/ruby is the place where the source code is extracted.

~/src/ruby % ./configure ~/src/ruby % make ~/src/ruby % su ~/src/ruby # make install

Below, I’ll describe several points to be careful about.

On some platforms like Cygwin, UX/4800,

you need to specify the --enable-shared option at the phase of configure,

or you’d fail to link.

--enable-shared is an option to put the most of ruby out of the command

as shared libraries (libruby.so).

~/src/ruby % ./configure --enable-shared

The detailed tutorial about building is included in doc/build.html of the

attached CD-ROM, I’d like you to try as reading it.

Building on Windows

If the thing is to build on windows, it becomes way complicated. The source of the problem is, there are multiple building environments.

- Visual C++

- MinGW

- Cygwin

- Borland C++ Compiler

First, the condition of the Cygwin environment is closer to UNIX than Windows, you can follow the building procedures for Unix-like OS.

If you’d like to compile with Visual C++, Visual C++ 5.0 and later is required. There’s probably no problem if it is version 6 or .NET.

MinGW or Minimalist GNU for Windows,

it is what the GNU compiling environment (Namely, gcc and binutils)

is ported on Windows.

Cygwin ports the whole UNIX environment.

On the contrary, MinGW ports only the tools to compile.

Moreover, a program compiled with MinGW does not require any special DLL at

runtime. It means, the ruby compiled with MinGW can be treated completely the

same as the Visual C++ version.

Alternatively, if it is personal use, you can download the version 5.5 of

Borland C++ Compiler for free from the site of Boarland.

\footnote{The Borland site: http://www.borland.co.jp}

Because ruby started to support this environment fairly recently,

there’s more or less anxiety,

but there was not any particular problem on the build test done before the

publication of this book.

Then, among the above four environments, which one should we choose? First, basically the Visual C++ version is the most unlikely to cause a problem, thus I recommend it. If you have experienced with UNIX, installing the whole Cygwin and using it is good. If you have not experienced with UNIX and you don’t have Visual C++, using MinGW is probably good.

Below, I’ll explain how to build with Visual C++ and MinGW,

but only about the outlines.

For more detailed explanations and how to build with Borland C++ Compiler,

they are included in doc/build.html of the attached CD-ROM,

thus I’d like you to check it when it is necessary.

Visual C++

It is said Visual C++, but usually IDE is not used, we’ll build from DOS prompt. In this case, first we need to initialize environment variables to be able to run Visual C++ itself. Since a batch file for this purpose came with Visual C++, let’s execute it first.

C:\> cd "\Program Files\Microsoft Visual Studio .NET\Vc7\bin" C:\Program Files\Microsoft Visual Studio .NET\Vc7\bin> vcvars32

This is the case of Visual C++ .NET. If it is version 6, it can be found in the following place.

C:\Program Files\Microsoft Visual Studio\VC98\bin\

After executing vcvars32,

all you have to do is to move to the win32\ folder of the source tree of

ruby and build. Below, let us suppose the source tree is in C:\src.

C:\> cd src\ruby C:\src\ruby> cd win32 C:\src\ruby\win32> configure C:\src\ruby\win32> nmake C:\src\ruby\win32> nmake DESTDIR="C:\Program Files\ruby" install

Then, ruby command would be installed in C:\Program Files\ruby\bin\,

and Ruby libraries would be in C:\Program Files\ruby\lib\.

Because ruby does not use registries and such at all,

you can uninstall it by deleting C:\Program Files\ruby and below.

MinGW

As described before, MinGW is only an environment to compile,

thus the general UNIX tools like sed or sh are not available.

However, because they are necessary to build ruby,

you need to obtain it from somewhere.

For this, there are also two methods:

Cygwin and MSYS (Minimal SYStem).

However, I can’t recommend MSYS because troubles were continuously happened at the building contest performed before the publication of this book. On the contrary, in the way of using Cygwin, it can pass very straightforwardly. Therefore, in this book, I’ll explain the way of using Cygwin.

First, install MinGW and the entire developing tools by using setup.exe of

Cygwin. Both Cygwin and MinGW are also included in the attached CD-ROM.

\footnote{Cygwin and MinGW……See also doc/win.html of the attached CD-ROM}

After that, all you have to do is to type as follows from bash prompt of Cygwin.

~/src/ruby % ./configure --with-gcc='gcc -mno-cygwin' \

--enable-shared i386-mingw32

~/src/ruby % make

~/src/ruby % make install

That’s it. Here the line of configure spans multi-lines but in practice

we’d write it on one line and the backslash is not necessary.

The place to install is \usr\local\ and below of the drive on which it is

compiled. Because really complicated things occur around here, the explanation

would be fairly long, so I’ll explain it comprehensively in doc/build.html of

the attached CD-ROM.

Building Details

Until here, it has been the README-like description.

This time, let’s look at exactly what is done by what we have been done.

However, the talks here partially require very high-level knowledge.

If you can’t understand, I’d like you to skip this and directly jump to the next

section. This should be written so that you can understand by coming back after

reading the entire book.

Now, on whichever platform, building ruby is separated into three phases.

Namely, configure, make and make install.

As considering the explanation about make install unnecessary,

I’ll explain the configure phase and the make phase.

configure

First, configure. Its content is a shell script, and we detect the system

parameters by using it. For example, “whether there’s the header file

setjmp.h” or “whether alloca() is available”, these things are checked.

The way to check is unexpectedly simple.

| Target to check | Method |

|---|---|

| commands | execute it actually and then check $? |

| header files | if [ -f $includedir/stdio.h ] |

| functions | compile a small program and check whether linking is success |

When some differences are detected, somehow it should be reported to us.

The way to report is,

the first way is Makefile.

If we put a Makefile.in in which parameters are embedded in the form of

`param`, it would generate a Makefile in which they are substituted

with the actual values.

For example, as follows,

Makefile.in: CFLAGS = @CFLAGS@

↓

Makefile : CFLAGS = -g -O2

Alternatively, it writes out the information about, for instance, whether

there are certain functions or particular header files, into a header file.

Because the output file name can be changed, it is different depending on each

program, but it is config.h in ruby.

I’d like you to confirm this file is created after executing configure.

Its content is something like this.

▼config.h

:

:

#define HAVE_SYS_STAT_H 1

#define HAVE_STDLIB_H 1

#define HAVE_STRING_H 1

#define HAVE_MEMORY_H 1

#define HAVE_STRINGS_H 1

#define HAVE_INTTYPES_H 1

#define HAVE_STDINT_H 1

#define HAVE_UNISTD_H 1

#define _FILE_OFFSET_BITS 64

#define HAVE_LONG_LONG 1

#define HAVE_OFF_T 1

#define SIZEOF_INT 4

#define SIZEOF_SHORT 2

:

:

Each meaning is easy to understand.

HAVE_xxxx_H probably indicates whether a certain header file exists,

SIZEOF_SHORT must indicate the size of the short type of C.

Likewise, SIZEOF_INT indicates the byte length of int,

HAVE_OFF_T indicates whether the offset_t type is defined or not.

As we can understand from the above things,

configure does detect the differences but it does not automatically absorb the

differences. Bridging the difference is left to each programmer.

For example, as follows,

▼ A typical usage of the `HAVE_` macro

24 #ifdef HAVE_STDLIB_H 25 # include26 #endif (ruby.h)

autoconf

configure is not a `ruby`-specific tool.

Whether there are functions, there are header files, …

it is obvious that these tests have regularity.

It is wasteful if each person who writes a program wrote each own distinct tool.

Here a tool named autoconf comes in.

In the files named configure.in or configure.ac,

write about “I’d like to do these checks”,

process it with autoconf,

then an adequate configure would be generated.

The .in of configure.in is probably an abbreviation of input.

It’s the same as the relationship between Makefile and Makefile.in.

.ac is, of course, an abbreviation of AutoConf.

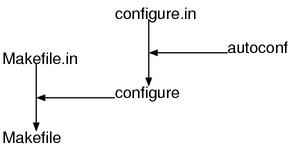

To illustrate this talk up until here, it would be like Figure 1.

For the readers who want to know more details, I recommend “GNU Autoconf/Automake/Libtool” Gary V.Vaughan, Ben Elliston, Tom Tromey, Ian Lance Taylor.

By the way, `ruby`‘s `configure` is, as said before, generated by using

autoconf, but not all the configure in this world are generated with

autoconf. It can be written by hand or another tool to automatically generate

can be used. Anyway, it’s sufficient if ultimately there are Makefile and

config.h and many others.

make

At the second phase, make, what is done?

Of course, it would compile the source code of ruby,

but when looking at the output of make,

I feel like there are many other things it does.

I’ll briefly explain the process of it.

- compile the source code composing

rubyitself - create the static library

libruby.agathering the crucial parts ofruby - create “

miniruby”, which is an always statically-linkedruby - create the shared library

libruby.sowhen--enable-shared - compile the extension libraries (under

ext/) by usingminiurby - At last, generate the real

ruby

There are two reasons why it creates miniruby and ruby separately.

The first one is that compiling the extension libraries requires ruby.

In the case when --enable-shared, ruby itself is dynamically linked,

thus there’s a possibility not be able to run instantly because of the load

paths of the libraries. Therefore, create miniruby, which is statically

linked, and use it during the building process.

The second reason is, in a platform where we cannot use shared libraries,

there’s a case when the extension libraries are statically linked to ruby

itself. In this case, it cannot create ruby before compiling all extension

libraries, but the extension libraries cannot be compiled without ruby.

In order to resolve this dilemma, it uses miniruby.

CVS

The ruby archive included in the attached CD-ROM is,

as the same as the official release package,

just a snapshot which is an appearance at just a particular moment of ruby,

which is a continuously changing program.

How ruby has been changed, why it has been so, these things are not described

there. Then what is the way to see the entire picture including the past.

We can do it by using CVS.

About CVS

CVS is shortly an undo list of editors. If the source code is under the management of CVS, the past appearance can be restored anytime, and we can understand who and where and when and how changed it immediately any time. Generally a program doing such job is called source code management system and CVS is the most famous open-source source code management system in this world.

Since ruby is also managed with CVS,

I’ll explain a little about the mechanism and usage of CVS.

First, the most important idea of CVS is repository and working-copy.

I said CVS is something like an undo list of editor,

in order to archive this, the records of every changing history should be saved

somewhere. The place to store all of them is “CVS repository”.

Directly speaking, repository is what gathers all the past source codes. Of course, this is only a concept, in reality, in order to save spaces, it is stored in the form of one recent appearance and the changing differences (namely, batches). In any ways, it is sufficient if we can obtain the appearance of a particular file of a particular moment any time.

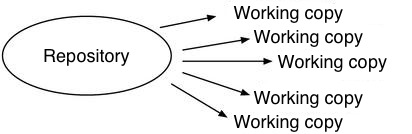

On the other hand, “working copy” is the result of taking files from the repository by choosing a certain point. There’s only one repository, but you can have multiple working copies. (Figure 2)

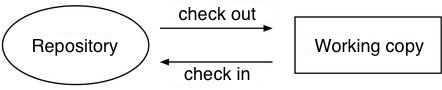

When you’d like to modify the source code, first take a working copy, edit it by using editor and such, and “return” it. Then, the change is recorded to the repository. Taking a working copy from the repository is called “checkout”, returning is called “checkin” or “commit” (Figure 3). By checking in, the change is recorded to the repository, then we can obtain it any time.

The biggest trait of CVS is we can access it over the networks. It means, if there’s only one server which holds the repository, everyone can checkin/checkout over the internet any time. But generally the access to check in is restricted and we can’t do it freely.

Revision

How can we do to obtain a certain version from the repository? One way is to specify with time. By requiring “give me the edge version of that time”, it would select it. But in practice, we rarely specify with time. Most commonly, we use something named “revision”.

“Revision” and “Version” have the almost same meaning. But usually “version” is attached to the project itself, thus using the word “version” can be confusing. Therefore, the word “revision” is used to indicate a bit smaller unit.

In CVS, the file just stored in the repository is revision 1.1. Checking out it, modifying it, checking in it, then it would be revision 1.2. Next it would be 1.3 then 1.4.

A simple usage example of CVS

Keeping in mind the above things,

I’ll talk about the usage of CVS very very briefly.

First, cvs command is essential, so I’d like you to install it beforehand.

The source code of cvs is included in the attached CD-ROM

\footnote{cvs:archives/cvs-1.11.2.tar.gz}.

How to install cvs is really far from the main line,

thus it won’t be explained here.

After installing it, let’s checkout the source code of ruby as an experiment.

Type the following commands when you are online.

% cvs -d :pserver:anonymous@cvs.ruby-lang.org:/src login CVS Password: anonymous % cvs -d :pserver:anonymous@cvs.ruby-lang.org:/src checkout ruby

Any options were not specified,

thus the edge version would be automatically checked out.

The truly edge version of ruby must appear under ruby/.

Additionally, if you’d like to obtain the version of a certain day,

you can use -D option of cvs checkout.

By typing as follows, you can obtain a working copy of the version which is

being explained by this book.

% cvs -d :pserver:anonymous@cvs.ruby-lang.org:/src checkout -D2002-09-12 ruby

At this moment, you have to write options immediately after checkout.

If you wrote “ruby” first, it would cause a strange error complaining “missing

a module”.

And, with the anonymous access like this example, we cannot check in.

In order to practice checking in, it’s good to create a (local) repository and

store a “Hello, World!” program in it.

The concrete way to store is not explained here.

The manual coming with cvs is fairly friendly.

Regarding books which you can read in Japanese,

I recommend translated “Open Source Development with CVS” Karl Fogel, Moshe Bar.

The composition of ruby

The physical structure

Now it is time to start to read the source code,

but what is the thing we should do first?

It is looking over the directory structure.

In most cases, the directory structure, meaning the source tree, directly

indicate the module structure of the program.

Abruptly searching main() by using grep and reading from the top in its

processing order is not smart.

Of course finding out main() is also important,

but first let’s take time to do ls or head to grasp the whole picture.

Below is the appearance of the top directory immediately after checking out from the CVS repository. What end with a slash are subdirectories.

COPYING compar.c gc.c numeric.c sample/ COPYING.ja config.guess hash.c object.c signal.c CVS/ config.sub inits.c pack.c sprintf.c ChangeLog configure.in install-sh parse.y st.c GPL cygwin/ instruby.rb prec.c st.h LEGAL defines.h intern.h process.c string.c LGPL dir.c io.c random.c struct.c MANIFEST djgpp/ keywords range.c time.c Makefile.in dln.c lex.c re.c util.c README dln.h lib/ re.h util.h README.EXT dmyext.c main.c regex.c variable.c README.EXT.ja doc/ marshal.c regex.h version.c README.ja enum.c math.c ruby.1 version.h ToDo env.h misc/ ruby.c vms/ array.c error.c missing/ ruby.h win32/ bcc32/ eval.c missing.h rubyio.h x68/ bignum.c ext/ mkconfig.rb rubysig.h class.c file.c node.h rubytest.rb

Recently the size of a program itself has become larger,

and there are many softwares whose subdirectories are divided into pieces,

but ruby has been consistently used the top directory for a long time.

It becomes problematic if there are too many files,

but we can get used to this amount.

The files at the top level can be categorized into six:

- documents

- the source code of

rubyitself - the tool to build

ruby - standard extension libraries

- standard Ruby libraries

- the others

The source code and the build tool are obviously important. Aside from them, I’ll list up what seems useful for us.

ChangeLog

The records of changes on ruby.

This is very important when investigating the reason of a certain change.

README.EXT README.EXT.ja

How to create an extension library is described,

but in the course of it, things relating to the implementation of ruby itself

are also written.

Dissecting Source Code

From now on, I’ll further split the source code of ruby itself into more tiny

pieces. As for the main files, its categorization is described in README.EXT,

thus I’ll follow it. Regarding what is not described, I categorized it by myself.

Ruby Language Core

class.c |

class relating API |

error.c |

exception relating API |

eval.c |

evaluator |

gc.c |

garbage collector |

lex.c |

reserved word table |

object.c |

object system |

parse.y |

parser |

variable.c |

constants, global variables, class variables |

ruby.h |

The main macros and prototypes of ruby |

intern.h |

the prototypes of C API of ruby.

intern seems to be an abbreviation of internal, but the functions written here

can be used from extension libraries. |

rubysig.h |

the header file containing the macros relating to signals |

node.h |

the definitions relating to the syntax tree nodes |

env.h |

the definitions of the structs to express the context of the evaluator |

The parts to compose the core of the ruby interpreter.

The most of the files which will be explained in this book are contained here.

If you consider the number of the files of the entire ruby,

it is really only a few. But if you think based on the byte size,

50% of the entire amount is occupied by these files.

Especially, eval.c is 200KB, parse.y is 100KB, these files are large.

Utility

| dln.c | dynamic loader |

| regex.c | regular expression engine |

| st.c | hash table |

| util.c | libraries for radix conversions and sort and so on |

It means utility for ruby.

However, some of them are so large that you cannot imagine it from the word

“utility”. For instance, regex.c is 120 KB.

Implementation of ruby command

dmyext.c |

dummy of the routine to initialize extension libraries ( DumMY EXTension ) |

inits.c |

the entry point for core and the routine to initialize extension libraries |

main.c |

the entry point of ruby command (this is unnecessary for

libruby ) |

ruby.c |

the main part of ruby command (this is also necessary for

libruby ) |

version.c |

the version of ruby |

The implementation of ruby command,

which is of when typing ruby on the command line and execute it.

This is the part, for instance, to interpret the command line options.

Aside from ruby command, as the commands utilizing ruby core,

there are mod_ruby and vim.

These commands are functioning by linking to the libruby library

(.a/.so/.dll and so on).

Class Libraries

array.c |

class Array |

bignum.c |

class Bignum |

compar.c |

module Comparable |

dir.c |

class Dir |

enum.c |

module Enumerable |

file.c |

class File |

hash.c |

class Hash (Its actual body is st.c) |

io.c |

class IO |

marshal.c |

module Marshal |

math.c |

module Math |

numeric.c |

class Numeric, Integer, Fixnum, Float |

pack.c |

Array#pack, String#unpack |

prec.c |

module Precision |

process.c |

module Process |

random.c |

Kernel#srand(), rand() |

range.c |

class Range |

re.c |

class Regexp (Its actual body is regex.c) |

signal.c |

module Signal |

sprintf.c |

ruby-specific sprintf() |

string.c |

class String |

struct.c |

class Struct |

time.c |

class Time |

The implementations of the Ruby class libraries. What listed here are basically implemented in the completely same way as the ordinary Ruby extension libraries. It means that these libraries are also examples of how to write an extension library.

Files depending on a particular platform

bcc32/ |

Borland C++ (Win32) |

beos/ |

BeOS |

cygwin/ |

Cygwin (the UNIX simulation layer on Win32) |

djgpp/ |

djgpp (the free developing environment for DOS) |

vms/ |

VMS (an OS had been released by DEC before) |

win32/ |

Visual C++ (Win32) |

x68/ |

Sharp X680x0 series (OS is Human68k) |

Each platform-specific code is stored.

fallback functions

missing/

Files to offset the functions which are missing on each platform.

Mainly functions of libc.

Logical Structure

Now, there are the above four groups and the core can be divided further into three: First, “object space” which creates the object world of Ruby. Second, “parser” which converts Ruby programs (in text) to the internal format. Third, “evaluator” which drives Ruby programs. Both parser and evaluator are composed above object space, parser converts a program into the internal format, and evaluator actuates the program. Let me explain them in order.

Object Space

The first one is object space. This is very easy to understand. It is because all of what dealt with by this are basically on the memory, thus we can directly show or manipulate them by using functions. Therefore, in this book, the explanation will start with this part. Part 1 is from chapter 2 to chapter 7.

Parser

The second one is parser. Probably some preliminary explanations are necessary for this.

ruby command is the interpreter of Ruby language.

It means that it analyzes the input which is a text on invocation

and executes it by following it.

Therefore, ruby needs to be able to interpret the meaning of the program

written as a text, but unfortunately text is very hard to understand for

computers. For computers, text files are merely byte sequences and nothing more than

that. In order to comprehend the meaning of text from it, some special gimmick

is necessary. And the gimmick is parser. By passing through parser, (a text as) a

Ruby program would be converted into the `ruby`-specific internal expression

which can be easily handled from the program.

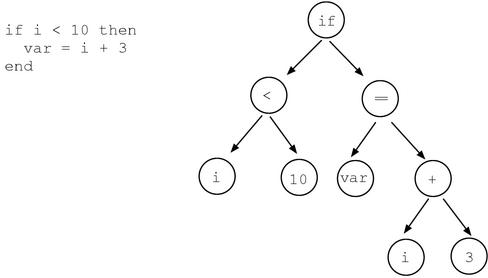

The internal expression is called “syntax tree”.

Syntax tree expresses a program by a tree structure,

for instance, figure 4 shows how an if statement is expressed.

Parser will be described in Part 2 “Syntactic Analysis”.

Part 2 is from chapter 10 to chapter 12.

Its target file is only parse.y.

Evaluator

Objects are easy to understand because they are tangible. Also regarding parser, What it does is ultimately converting a data format into another one, so it’s reasonably easy to understand. However, the third one, evaluator, this is completely elusive.

What evaluator does is “executing” a program by following a syntax tree.

This sounds easy, but what is “executing”?

To answer this question precisely is fairly difficult.

What is “executing an if statement”?

What is “executing a while statement”?

What does “assigning to a local variable” mean?

We cannot understand evaluator without answering all of such questions clearly

and precisely.

In this book, evaluator will be discussed in Part 3 “Evaluate”.

Its target file is eval.c.

eval is an abbreviation of “evaluator”.

Now, I’ve described briefly about the structure of ruby,

however even though the ideas were explained,

it does not so much help us understand the behavior of program.

In the next chapter, we’ll start with actually using ruby.