Ruby Hacking Guide

Chapter 17: Dynamic evaluation

Overview

I have already finished to describe about the mechanism of the evaluator by the previous chapter. In this chapter, by including the parser in addition to it, let’s examine the big picture as “the evaluator in a broad sense”. There are three targets: `eval`, `Module#module_eval` and `Object#instance_eval`.

`eval`

I’ve already described about `eval`, but I’ll introduce more tiny things about it here.

By using `eval`, you can compile and evaluate a string at runtime in the place. Its return value is the value of the last expression of the program.

p eval("1 + 1") # 2

You can also refer to a variable in its scope from inside of a string to `eval`.

lvar = 5

@ivar = 6

p eval("lvar + @ivar") # 11

Readers who have been reading until here cannot simply read and pass over the word “its scope”. For instance, you are curious about how is its “scope” of constants, aren’t you? I am. To put the bottom line first, basically you can think it directly inherits the environment of outside of `eval`.

And you can also define methods and define classes.

def a

eval('class C; def test() puts("ok") end end')

end

a() # define class C and C#test

C.new.test # shows ok

Moreover, as mentioned a little in the previous chapter, when you pass a `Proc` as the second argument, the string can be evaluated in its environment.

def new_env

n = 5

Proc.new { nil } # turn the environment of this method into an object and return it

end

p eval('n * 3', new_env()) # 15

`module_eval` and `instance_eval`

When a `Proc` is passed as the second argument of `eval`, the evaluations can be done in its environment. `module_eval` and `instance_eval` is its limited (or shortcut) version. With `module_eval`, you can evaluate in an environment that is as if in a module statement or a class statement.

lvar = "toplevel lvar" # a local variable to confirm this scope

module M

end

M.module_eval(<<'EOS') # a suitable situation to use here-document

p lvar # referable

p self # shows M

def ok # define M#ok

puts 'ok'

end

EOS

With `instance_eval`, you can evaluate in an environment whose `self` of the singleton class statement is the object.

lvar = "toplevel lvar" # a local variable to confirm this scope

obj = Object.new

obj.instance_eval(<<'EOS')

p lvar # referable

p self # shows #<Object:0x40274f5c>

def ok # define obj.ok

puts 'ok'

end

EOS

Additionally, these `module_eval` and `instance_eval` can also be used as iterators, a block is evaluated in each environment in that case. For instance,

obj = Object.new

p obj # #<Object:0x40274fac>

obj.instance_eval {

p self # #<Object:0x40274fac>

}

Like this.

However, between the case when using a string and the case when using a block, the behavior around local variables is different each other. For example, when creating a block in the `a` method then doing `instance_eval` it in the `b` method, the block would refer to the local variables of `a`. When creating a string in the `a` method then doing `instance_eval` it in the `b` method, from inside of the string, it would refer to the local variables of `b`. The scope of local variables is decided “at compile time”, the consequence differs because a string is compiled every time but a block is compiled when loading files.

`eval`

`eval()`

The `eval` of Ruby branches many times based on the presence and absence of the parameters. Let’s assume the form of call is limited to the below:

eval(prog_string, some_block)

Then, since this makes the actual interface function `rb_f_eval()` almost meaningless, we’ll start with the function `eval()` which is one step lower. The function prototype of `eval()` is:

static VALUE eval(VALUE self, VALUE src, VALUE scope, char *file, int line);

`scope` is the `Proc` of the second parameter. `file` and `line` is the file name and line number of where a string to `eval` is supposed to be located. Then, let’s see the content:

▼ `eval()` (simplified)

4984 static VALUE

4985 eval(self, src, scope, file, line)

4986 VALUE self, src, scope;

4987 char *file;

4988 int line;

4989 {

4990 struct BLOCK *data = NULL;

4991 volatile VALUE result = Qnil;

4992 struct SCOPE * volatile old_scope;

4993 struct BLOCK * volatile old_block;

4994 struct RVarmap * volatile old_dyna_vars;

4995 VALUE volatile old_cref;

4996 int volatile old_vmode;

4997 volatile VALUE old_wrapper;

4998 struct FRAME frame;

4999 NODE *nodesave = ruby_current_node;

5000 volatile int iter = ruby_frame->iter;

5001 int state;

5002

5003 if (!NIL_P(scope)) { /* always true now */

5009 Data_Get_Struct(scope, struct BLOCK, data);

5010 /* push BLOCK from data */

5011 frame = data->frame;

5012 frame.tmp = ruby_frame; /* to prevent from GC */

5013 ruby_frame = &(frame);

5014 old_scope = ruby_scope;

5015 ruby_scope = data->scope;

5016 old_block = ruby_block;

5017 ruby_block = data->prev;

5018 old_dyna_vars = ruby_dyna_vars;

5019 ruby_dyna_vars = data->dyna_vars;

5020 old_vmode = scope_vmode;

5021 scope_vmode = data->vmode;

5022 old_cref = (VALUE)ruby_cref;

5023 ruby_cref = (NODE*)ruby_frame->cbase;

5024 old_wrapper = ruby_wrapper;

5025 ruby_wrapper = data->wrapper;

5032 self = data->self;

5033 ruby_frame->iter = data->iter;

5034 }

5045 PUSH_CLASS();

5046 ruby_class = ruby_cbase; /* == ruby_frame->cbase */

5047

5048 ruby_in_eval++;

5049 if (TYPE(ruby_class) == T_ICLASS) {

5050 ruby_class = RBASIC(ruby_class)->klass;

5051 }

5052 PUSH_TAG(PROT_NONE);

5053 if ((state = EXEC_TAG()) == 0) {

5054 NODE *node;

5055

5056 result = ruby_errinfo;

5057 ruby_errinfo = Qnil;

5058 node = compile(src, file, line);

5059 if (ruby_nerrs > 0) {

5060 compile_error(0);

5061 }

5062 if (!NIL_P(result)) ruby_errinfo = result;

5063 result = eval_node(self, node);

5064 }

5065 POP_TAG();

5066 POP_CLASS();

5067 ruby_in_eval--;

5068 if (!NIL_P(scope)) { /* always true now */

5069 int dont_recycle = ruby_scope->flags & SCOPE_DONT_RECYCLE;

5070

5071 ruby_wrapper = old_wrapper;

5072 ruby_cref = (NODE*)old_cref;

5073 ruby_frame = frame.tmp;

5074 ruby_scope = old_scope;

5075 ruby_block = old_block;

5076 ruby_dyna_vars = old_dyna_vars;

5077 data->vmode = scope_vmode; /* save the modification of the visibility scope */

5078 scope_vmode = old_vmode;

5079 if (dont_recycle) {

/* ……copy SCOPE BLOCK VARS…… */

5097 }

5098 }

5104 if (state) {

5105 if (state == TAG_RAISE) {

/* ……prepare an exception object…… */

5121 rb_exc_raise(ruby_errinfo);

5122 }

5123 JUMP_TAG(state);

5124 }

5125

5126 return result;

5127 }

(eval.c)

If this function is shown without any preamble, you probably feel “oww!”. But we’ve defeated many functions of `eval.c` until here, so this is not enough to be an enemy of us. This function is just continuously saving/restoring the stacks. The points we need to care about are only the below three:

- unusually `FRAME` is also replaced (not copied and pushed)

- `ruby_cref` is substituted (?) by `ruby_frame→cbase`

- only `scope_vmode` is not simply restored but influences `data`.

And the main parts are the `compile()` and `eval_node()` located around the middle. Though it’s possible that `eval_node()` has already been forgotten, it is the function to start the evaluation of the parameter `node`. It was also used in `ruby_run()`.

Here is `compile()`.

▼ `compile()`

4968 static NODE*

4969 compile(src, file, line)

4970 VALUE src;

4971 char *file;

4972 int line;

4973 {

4974 NODE *node;

4975

4976 ruby_nerrs = 0;

4977 Check_Type(src, T_STRING);

4978 node = rb_compile_string(file, src, line);

4979

4980 if (ruby_nerrs == 0) return node;

4981 return 0;

4982 }

(eval.c)

`ruby_nerrs` is the variable incremented in `yyerror()`. In other words, if this variable is non-zero, it indicates more than one parse error happened. And, `rb_compile_string()` was already discussed in Part 2. It was a function to compile a Ruby string into a syntax tree.

One thing becomes a problem here is local variable. As we’ve seen in Chapter 12: Syntax tree construction, local variables are managed by using `lvtbl`. However, since a `SCOPE` (and possibly also `VARS`) already exists, we need to parse in the way of writing over and adding to it. This is in fact the heart of `eval()`, and is the worst difficult part. Let’s go back to `parse.y` again and complete this investigation.

`top_local`

I’ve mentioned that the functions named `local_push() local_pop()` are used when pushing `struct local_vars`, which is the management table of local variables, but actually there’s one more pair of functions to push the management table. It is the pair of `top_local_init()` and `top_local_setup()`. They are called in this sort of way.

▼ How `top_local_init()` is called

program : { top_local_init(); }

compstmt

{ top_local_setup(); }

Of course, in actuality various other things are also done, but all of them are cut here because it’s not important. And this is the content of it:

▼ `top_local_init()`

5273 static void

5274 top_local_init()

5275 {

5276 local_push(1);

5277 lvtbl->cnt = ruby_scope->local_tbl?ruby_scope->local_tbl[0]:0;

5278 if (lvtbl->cnt > 0) {

5279 lvtbl->tbl = ALLOC_N(ID, lvtbl->cnt+3);

5280 MEMCPY(lvtbl->tbl, ruby_scope->local_tbl, ID, lvtbl->cnt+1);

5281 }

5282 else {

5283 lvtbl->tbl = 0;

5284 }

5285 if (ruby_dyna_vars)

5286 lvtbl->dlev = 1;

5287 else

5288 lvtbl->dlev = 0;

5289 }

(parse.y)

This means that `local_tbl` is copied from `ruby_scope` to `lvtbl`. As for block local variables, since it’s better to see them all at once later, we’ll focus on ordinary local variables for the time being. Next, here is `top_local_setup()`.

▼ `top_local_setup()`

5291 static void

5292 top_local_setup()

5293 {

5294 int len = lvtbl->cnt; /* the number of local variables after parsing */

5295 int i; /* the number of local varaibles before parsing */

5296

5297 if (len > 0) {

5298 i = ruby_scope->local_tbl ? ruby_scope->local_tbl[0] : 0;

5299

5300 if (i < len) {

5301 if (i == 0 || (ruby_scope->flags & SCOPE_MALLOC) == 0) {

5302 VALUE *vars = ALLOC_N(VALUE, len+1);

5303 if (ruby_scope->local_vars) {

5304 *vars++ = ruby_scope->local_vars[-1];

5305 MEMCPY(vars, ruby_scope->local_vars, VALUE, i);

5306 rb_mem_clear(vars+i, len-i);

5307 }

5308 else {

5309 *vars++ = 0;

5310 rb_mem_clear(vars, len);

5311 }

5312 ruby_scope->local_vars = vars;

5313 ruby_scope->flags |= SCOPE_MALLOC;

5314 }

5315 else {

5316 VALUE *vars = ruby_scope->local_vars-1;

5317 REALLOC_N(vars, VALUE, len+1);

5318 ruby_scope->local_vars = vars+1;

5319 rb_mem_clear(ruby_scope->local_vars+i, len-i);

5320 }

5321 if (ruby_scope->local_tbl &&

ruby_scope->local_vars[-1] == 0) {

5322 free(ruby_scope->local_tbl);

5323 }

5324 ruby_scope->local_vars[-1] = 0; /* NODE is not necessary anymore */

5325 ruby_scope->local_tbl = local_tbl();

5326 }

5327 }

5328 local_pop();

5329 }

(parse.y)

Since `local_vars` can be either in the stack or in the heap, it makes the code complex to some extent. However, this is just updating `local_tbl` and `local_vars` of `ruby_scope`. (When `SCOPE_MALLOC` was set, `local_vars` was allocated by `malloc()`). And here, because there’s no meaning of using `alloca()`, it is forced to change its allocation method to `malloc`.

Block Local Variable

By the way, how about block local variables? To think about this, we have to go back to the entry point of the parser first, it is `yycompile()`.

▼ setting `ruby_dyna_vars` aside

static NODE*

yycompile(f, line)

{

struct RVarmap *vars = ruby_dyna_vars;

:

n = yyparse();

:

ruby_dyna_vars = vars;

}

This looks like a mere save-restore, but the point is that this does not clear the `ruby_dyna_vars`. This means that also in the parser it directly adds elements to the link of `RVarmap` created in the evaluator.

However, according to the previous description, the structure of `ruby_dyna_vars` differs between the parser and the evalutor. How does it deal with the difference in the way of attaching the header (`RVarmap` whose `id=0`)?

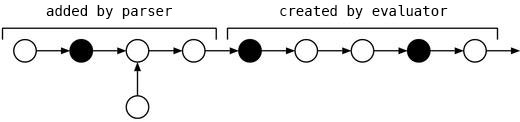

What is helpful here is the “1” of `local_push(1)` in `top_local_init()`. When the argument of `local_push()` becomes true, it does not attach the first header of `ruby_dyna_vars`. It means, it would look like Figure 1. Now, it is assured that we can refer to the block local variables of the outside scope from inside of a string to `eval`.

Figure 1: `ruby_dyna_vars` inside `eval`

Well, it’s sure we can refer to, but didn’t you say that `ruby_dyna_vars` is entirely freed in the parser? What can we do if the link created at the evaluator will be freed? … I’d like the readers who noticed this to be relieved by reading the next part.

▼ `yycompile()` − freeing `ruby_dyna_vars`

2386 vp = ruby_dyna_vars;

2387 ruby_dyna_vars = vars;

2388 lex_strterm = 0;

2389 while (vp && vp != vars) {

2390 struct RVarmap *tmp = vp;

2391 vp = vp->next;

2392 rb_gc_force_recycle((VALUE)tmp);

2393 }

(parse.y)

It is designed so that the loop would stop when it reaches the link created at the evaluator (`vars`).

`instance_eval`

The Whole Picture

The substance of `Module#module_eval` is `rb_mod_module_eval()`, and the substance of `Object#instance_eval` is `rb_obj_instance_eval()`.

▼ `rb_mod_module_eval() rb_obj_instance_eval()`

5316 VALUE

5317 rb_mod_module_eval(argc, argv, mod)

5318 int argc;

5319 VALUE *argv;

5320 VALUE mod;

5321 {

5322 return specific_eval(argc, argv, mod, mod);

5323 }

5298 VALUE

5299 rb_obj_instance_eval(argc, argv, self)

5300 int argc;

5301 VALUE *argv;

5302 VALUE self;

5303 {

5304 VALUE klass;

5305

5306 if (rb_special_const_p(self)) {

5307 klass = Qnil;

5308 }

5309 else {

5310 klass = rb_singleton_class(self);

5311 }

5312

5313 return specific_eval(argc, argv, klass, self);

5314 }

(eval.c)

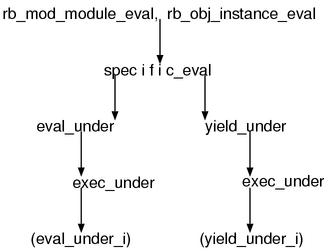

These two methods have a common part as “a method to replace `self` with `class`”, that part is defined as `specific_eval()`. Figure 2 shows it and also what will be described. What with parentheses are calls by function pointers.

Figure 2: Call Graph

Whichever `instance_eval` or `module_eval`, it can accept both a block and a string, thus it branches for each particular process to `yield` and `eval` respectively. However, most of them are also common again, this part is extracted as `exec_under()`.

But for those who reading, one have to simultaneously face at 2 times 2 = 4 ways, it is not a good plan. Therefore, here we assume only the case when

- it is an `instance_eval`

- which takes a string as its argument

. And extracting all functions under `rb_obj_instance_eval()` in-line, folding constants, we’ll read the result.

After Absorbed

After all, it becomes very comprehensible in comparison to the one before being absorbed.

▼specific_eval()−instance_eval, eval, string

static VALUE

instance_eval_string(self, src, file, line)

VALUE self, src;

const char *file;

int line;

{

VALUE sclass;

VALUE result;

int state;

int mode;

sclass = rb_singleton_class(self);

PUSH_CLASS();

ruby_class = sclass;

PUSH_FRAME();

ruby_frame->self = ruby_frame->prev->self;

ruby_frame->last_func = ruby_frame->prev->last_func;

ruby_frame->last_class = ruby_frame->prev->last_class;

ruby_frame->argc = ruby_frame->prev->argc;

ruby_frame->argv = ruby_frame->prev->argv;

if (ruby_frame->cbase != sclass) {

ruby_frame->cbase = rb_node_newnode(NODE_CREF, sclass, 0,

ruby_frame->cbase);

}

PUSH_CREF(sclass);

mode = scope_vmode;

SCOPE_SET(SCOPE_PUBLIC);

PUSH_TAG(PROT_NONE);

if ((state = EXEC_TAG()) == 0) {

result = eval(self, src, Qnil, file, line);

}

POP_TAG();

SCOPE_SET(mode);

POP_CREF();

POP_FRAME();

POP_CLASS();

if (state) JUMP_TAG(state);

return result;

}

It seems that this pushes the singleton class of the object to `CLASS` and `CREF` and `ruby_frame→cbase`. The main process is one-shot of `eval()`. It is unusual that things such as initializing `FRAME` by a struct-copy are missing, but this is also not create so much difference.

Before being absorbed

Though the author said it becomes more friendly to read, it’s possible it has been already simple since it was not absorbed, let’s check where is simplified in comparison to the before-absorbed one.

The first one is `specific_eval()`. Since this function is to share the code of the interface to Ruby, almost all parts of it is to parse the parameters. Here is the result of cutting them all.

▼ `specific_eval()` (simplified)

5258 static VALUE

5259 specific_eval(argc, argv, klass, self)

5260 int argc;

5261 VALUE *argv;

5262 VALUE klass, self;

5263 {

5264 if (rb_block_given_p()) {

5268 return yield_under(klass, self);

5269 }

5270 else {

5294 return eval_under(klass, self, argv[0], file, line);

5295 }

5296 }

(eval.c)

As you can see, this is perfectly branches in two ways based on whether there’s a block or not, and each route would never influence the other. Therefore, when reading, we should read one by one. To begin with, the absorbed version is enhanced in this point.

And `file` and `line` are irrelevant when reading `yield_under()`, thus in the case when the route of `yield` is absorbed by the main body, it might become obvious that we don’t have to think about the parse of these parameters at all.

Next, we’ll look at `eval_under()` and `eval_under_i()`.

▼ `eval_under()`

5222 static VALUE

5223 eval_under(under, self, src, file, line)

5224 VALUE under, self, src;

5225 const char *file;

5226 int line;

5227 {

5228 VALUE args[4];

5229

5230 if (ruby_safe_level >= 4) {

5231 StringValue(src);

5232 }

5233 else {

5234 SafeStringValue(src);

5235 }

5236 args[0] = self;

5237 args[1] = src;

5238 args[2] = (VALUE)file;

5239 args[3] = (VALUE)line;

5240 return exec_under(eval_under_i, under, under, args);

5241 }

5214 static VALUE

5215 eval_under_i(args)

5216 VALUE *args;

5217 {

5218 return eval(args[0], args[1], Qnil, (char*)args[2], (int)args[3]);

5219 }

(eval.c)

In this function, in order to make its arguments single, it stores them into the `args` array and passes it. We can imagine that this `args` exists as a temporary container to pass from `eval_under()` to `eval_under_i()`, but not sure that it is truly so. It’s possible that `args` is modified inside `evec_under()`.

As a way to share a code, this is a very right way to do. But for those who read it, this kind of indirect passing is incomprehensible. Particularly, because there are extra castings for `file` and `line` to fool the compiler, it is hard to imagine what were their actual types. The parts around this entirely disappeared in the absorbed version, so you don’t have to worry about getting lost.

However, it’s too much to say that absorbing and extracting always makes things easier to understand. For example, when calling `exec_under()`, `under` is passed as both the second and third arguments, but is it all right if the `exec_under()` side extracts the both parameter variables into `under`? That is to say, the second and third arguments of `exec_under()` are, in fact, indicating `CLASS` and `CREF` that should be pushed. `CLASS` and `CREF` are “different things”, it might be better to use different variables. Also in the previous absorbed version, for only this point,

VALUE sclass = .....; VALUE cbase = sclass;

I thought that I would write this way, but also thought it could give the strange impression if abruptly only these variables are left, thus it was extracted as `sclass`. It means that this is only because of the flow of the texts.

By now, so many times, I’ve extracted arguments and functions, and for each time I repeatedly explained the reason to extract. They are

- there are only a few possible patterns

- the behavior can slightly change

Definitely, I’m not saying “In whatever ways extracting various things always makes things simpler”.

In whatever case, what of the first priority is the comprehensibility for ourself and not keep complying the methodology. When extracting makes things simpler, extract it. When we feel that not extracting or conversely bundling as a procedure makes things easier to understand, let us do it. As for `ruby`, I often extracted them because the original is written properly, but if a source code was written by a poor programmer, aggressively bundling to functions should often become a good choice.