Ruby Hacking Guide

Translated by Vincent ISAMBART

Chapter 4: Classes and modules

In this chapter, we’ll see the details of the data structures created by classes and modules.

Classes and methods definition

First, I’d like to have a look at how Ruby classes are defined at the C level. This chapter investigates almost only particular cases, so I’d like you to know first the way used most often.

The main API to define classes and modules consists of the following 6 functions:

- `rb_define_class()`

- `rb_define_class_under()`

- `rb_define_module()`

- `rb_define_module_under()`

- `rb_define_method()`

- `rb_define_singleton_method()`

There are a few other versions of these functions, but the extension libraries and even most of the core library is defined using just this API. I’ll introduce to you these functions one by one.

Class definition

`rb_define_class()` defines a class at the top-level. Let’s take the Ruby array class, `Array`, as an example.

▼ `Array` class definition

19 VALUE rb_cArray;1809 void 1810 Init_Array() 1811 { 1812 rb_cArray = rb_define_class(“Array”, rb_cObject);

(array.c)

`rb_cObject` and `rb_cArray` correspond respectively to `Object` and `Array` at the Ruby level. The added prefix `rb` shows that it belongs to `ruby` and the `c` that it is a class object. These naming rules are used everywhere in `ruby`.

This call to `rb_define_class()` defines a class called `Array`, which inherits from `Object`. At the same time as `rb_define_class()` creates the class object, it also defines the constant. That means that after this you can already access `Array` from a Ruby program. It corresponds to the following Ruby program:

class Array < Object

I’d like you to note the fact that there is no `end`. It was written like this on purpose. It is because with `rb_define_class()` the body of the class has not been executed.

Nested class definition

After that, there’s `rb_define_class_under()`. This function defines a class nested in an other class or module. This time the example is what is returned by `stat(2)`, `File::Stat`.

▼ Definition of `File::Stat`

78 VALUE rb_cFile; 80 static VALUE rb_cStat;2581 rb_cFile = rb_define_class(“File”, rb_cIO); 2674 rb_cStat = rb_define_class_under(rb_cFile, “Stat”, rb_cObject);

(file.c)

This code corresponds to the following Ruby program;

class File < IO class Stat < Object

This time again I omitted the `end` on purpose.

Module definition

`rb_define_module()` is simple so let’s end this quickly.

▼ Definition of `Enumerable`

17 VALUE rb_mEnumerable; 492 rb_mEnumerable = rb_define_module(“Enumerable”);(enum.c)

The `m` in the beginning of `rb_mEnumerable` is similar to the `c` for classes: it shows that it is a module. The corresponding Ruby program is:

module Enumerable

`rb_define_module_under()` is not used much so we’ll skip it.

Method definition

This time the function is the one for defining methods, `rb_define_method()`. It’s used very often. We’ll take once again an example from `Array`.

▼ Definition of `Array#to_s`

1818 rb_define_method(rb_cArray, “to_s”, rb_ary_to_s, 0);(array.c)

With this the `to_s` method is defined in `Array`. The method body is given by a function pointer (`rb_ary_to_s`). The fourth parameter is the number of parameters taken by the method. As `to_s` does not take any parameters, it’s 0. If we write the corresponding Ruby program, we’ll have this:

class Array < Object

def to_s

# content of rb_ary_to_s()

end

end

Of course the `class` part is not included in `rb_define_method()` and only the `def` part is accurate. But if there is no `class` part, it will look like the method is defined like a function, so I also wrote the enclosing `class` part.

One more example, this time taking a parameter:

▼ Definition of `Array#concat`

1835 rb_define_method(rb_cArray, “concat”, rb_ary_concat, 1);(array.c)

The class for the definition is `rb_cArray` (`Array`), the method name is `concat`, its body is `rb_ary_concat()` and the number of parameters is 1. It corresponds to writing the corresponding Ruby program:

class Array < Object

def concat( str )

# content of rb_ary_concat()

end

end

Singleton methods definition

We can define methods that are specific to a single object instance. They are called singleton methods. As I used `File.unlink` as an example in chapter 1 “Ruby language minimum”, I first wanted to show it here, but for a particular reason we’ll look at `File.link` instead.

▼ Definition of `File.link`

2624 rb_define_singleton_method(rb_cFile, “link”, rb_file_s_link, 2);(file.c)

It’s used like `rb_define_method()`. The only difference is that here the first parameter is just the “object” where the method is defined. In this case, it’s defined in `rb_cFile`.

Entry point

Being able to make definitions like before is great, but where are these functions called from, and by what means are they executed? These definitions are grouped in functions named `Init_xxxx()`. For instance, for `Array` a function `Init_Array()` like this has been made:

▼ `Init_Array`

1809 void

1810 Init_Array()

1811 {

1812 rb_cArray = rb_define_class(“Array”, rb_cObject);

1813 rb_include_module(rb_cArray, rb_mEnumerable);

1814

1815 rb_define_singleton_method(rb_cArray, “allocate”,

rb_ary_s_alloc, 0);

1816 rb_define_singleton_method(rb_cArray, “[]”, rb_ary_s_create, -1);

1817 rb_define_method(rb_cArray, “initialize”, rb_ary_initialize, -1);

1818 rb_define_method(rb_cArray, “to_s”, rb_ary_to_s, 0);

1819 rb_define_method(rb_cArray, “inspect”, rb_ary_inspect, 0);

1820 rb_define_method(rb_cArray, “to_a”, rb_ary_to_a, 0);

1821 rb_define_method(rb_cArray, “to_ary”, rb_ary_to_a, 0);

1822 rb_define_method(rb_cArray, “frozen?”, rb_ary_frozen_p, 0);

(array.c)

The `Init` for the built-in functions are explicitly called during the startup of `ruby`. This is done in `inits.c`.

▼ `rb_call_inits()`

47 void

48 rb_call_inits()

49 {

50 Init_sym();

51 Init_var_tables();

52 Init_Object();

53 Init_Comparable();

54 Init_Enumerable();

55 Init_Precision();

56 Init_eval();

57 Init_String();

58 Init_Exception();

59 Init_Thread();

60 Init_Numeric();

61 Init_Bignum();

62 Init_Array();

(inits.c)

This way, `Init_Array()` is called properly.

That explains it for the built-in libraries, but what about extension libraries? In fact, for extension libraries the convention is the same. Take the following code:

require "myextension"

With this, if the loaded extension library is `myextension.so`, at load time, the (`extern`) function named `Init_myextension()` is called. How they are called is beyond the scope of this chapter. For that, you should read chapter 18, “Load”. Here we’ll just end this with an example of `Init`.

The following example is from `stringio`, an extension library provided with `ruby`, that is to say not from a built-in library.

▼ `Init_stringio()` (beginning)

895 void

896 Init_stringio()

897 {

898 VALUE StringIO = rb_define_class(“StringIO”, rb_cData);

899 rb_define_singleton_method(StringIO, “allocate”,

strio_s_allocate, 0);

900 rb_define_singleton_method(StringIO, “open”, strio_s_open, -1);

901 rb_define_method(StringIO, “initialize”, strio_initialize, -1);

902 rb_enable_super(StringIO, “initialize”);

903 rb_define_method(StringIO, “become”, strio_become, 1);

904 rb_define_method(StringIO, “reopen”, strio_reopen, -1);

(ext/stringio/stringio.c)

Singleton classes

`rb_define_singleton_method()`

You should now be able to more or less understand how normal methods are defined. Somehow making the body of the method, then registering it in `m_tbl` will do. But what about singleton methods? We’ll now look into the way singleton methods are defined.

▼ `rb_define_singleton_method()`

721 void 722 rb_define_singleton_method(obj, name, func, argc) 723 VALUE obj; 724 const char name; 725 VALUE (func)(); 726 int argc; 727 { 728 rb_define_method(rb_singleton_class(obj), name, func, argc); 729 }(class.c)

As I explained, `rb_define_method()` is a function used to define normal methods, so the difference from normal methods is only `rb_singleton_class()`. But what on earth are singleton classes?

In brief, singleton classes are virtual classes that are only used to execute singleton methods. Singleton methods are functions defined in singleton classes. Classes themselves are in the first place (in a way) the “implementation” to link objects and methods, but singleton classes are even more on the implementation side. In the Ruby language way, they are not formally included, and don’t appear much at the Ruby level.

`rb_singleton_class()`

Well, let’s confirm what the singleton classes are made of. It’s too simple to just show you the code of a function each time so this time I’ll use a new weapon, a call graph.

rb_define_singleton_method

rb_define_method

rb_singleton_class

SPECIAL_SINGLETON

rb_make_metaclass

rb_class_boot

rb_singleton_class_attached

Call graphs are graphs showing calling relationships among functions (or more generally procedures). The call graphs showing all the calls written in the source code are called static call graphs. The ones expressing only the calls done during an execution are called dynamic call graphs.

This diagram is a static call graph and the indentation expresses which function calls which one. For instance, `rb_define_singleton_method()` calls `rb_define_method()` and `rb_singleton_class()`. And this `rb_singleton_class()` itself calls `SPECIAL_SINGLETON()` and `rb_make_metaclass()`. In order to obtain call graphs, you can use `cflow` and such. {`cflow`: see also `doc/callgraph.html` in the attached CD-ROM}

In this book, because I wanted to obtain call graphs that contain only functions, I created a `ruby`-specific tool by myself. Perhaps it can be generalized by modifying its code analyzing part, thus I’d like to somehow make it until around the publication of this book. These situations are also explained in `doc/callgraph.html` of the attached CD-ROM.

Let’s go back to the code. When looking at the call graph, you can see that the calls made by `rb_singleton_class()` go very deep. Until now all call levels were shallow, so we could simply look at the functions without getting too lost. But at this depth, I easily forget what I was doing. In such situation you must bring a call graph to keep aware of where it is when reading. This time, as an example, we’ll decode the procedures below `rb_singleton_class()` in parallel. We should look out for the following two points:

- What exactly are singleton classes?

- What is the purpose of singleton classes?

Normal classes and singleton classes

Singleton classes are special classes: they’re basically the same as normal classes, but there are a few differences. We can say that finding these differences is explaining concretely singleton classes.

What should we do to find them? We should find the differences between the function creating normal classes and the one creating singleton classes. For this, we have to find the function for creating normal classes. That is as normal classes can be defined by `rb_define_class()`, it must call in a way or another a function to create normal classes. For the moment, we’ll not look at the content of `rb_define_class()` itself. I have some reasons to be interested in something that’s deeper. That’s why we will first look at the call graph of `rb_define_class()`.

rb_define_class

rb_class_inherited

rb_define_class_id

rb_class_new

rb_class_boot

rb_make_metaclass

rb_class_boot

rb_singleton_class_attached

I’m interested by `rb_class_new()`. Doesn’t this name means it creates a new class? Let’s confirm that.

▼ `rb_class_new()`

37 VALUE 38 rb_class_new(super) 39 VALUE super; 40 { 41 Check_Type(super, T_CLASS); 42 if (super == rb_cClass) { 43 rb_raise(rb_eTypeError, “can’t make subclass of Class”); 44 } 45 if (FL_TEST(super, FL_SINGLETON)) { 46 rb_raise(rb_eTypeError, “can’t make subclass of virtual class”); 47 } 48 return rb_class_boot(super); 49 }(class.c)

`Check_Type()` is checks the type of object structure, so we can ignore it. `rb_raise()` is error handling so we can ignore it. Only `rb_class_boot()` remains. So let’s look at it.

▼ `rb_class_boot()`

21 VALUE 22 rb_class_boot(super) 23 VALUE super; 24 { 25 NEWOBJ; /* allocates struct RClass / 26 OBJSETUP; / initialization of the RBasic part / 27 28 klass→super = super; / (A) */ 29 klass→iv_tbl = 0; 30 klass→m_tbl = 0; 31 klass→m_tbl = st_init_numtable(); 32 33 OBJ_INFECT(klass, super); 34 return (VALUE)klass; 35 }(class.c)

`NEWOBJ` are fixed expressions used when creating Ruby objects that possess one of the built-in structure types (`struct Rxxxx`). They are both macros. In `NEWOBJ`, the struct `RBasic` member of the `RClass` (and thus `basic.klass` and `basic.flags`) is initialized.

`OBJ_INFECT()` is a macro related to security. From now on, we’ll ignore it.

At (A), the `super` member of `klass`is set to the `super` parameter. It looks like `rb_class_boot()` is a function that creates a class inheriting from `super`.

So, as `rb_class_boot()` is a function that creates a class, and `rb_class_new()` is almost identical.

Then, let’s once more look at `rb_singleton_class()`’s call graph:

rb_singleton_class

SPECIAL_SINGLETON

rb_make_metaclass

rb_class_boot

rb_singleton_class_attached

Here also `rb_class_boot()` is called. So up to that point, it’s the same as in normal classes. What’s going on after is what’s different between normal classes and singleton classes, in other words the characteristics of singleton classes. If everything’s clear so far, we just need to read `rb_singleton_class()` and `rb_make_metaclass()`.

Compressed `rb_singleton_class()`

`rb_singleton_class()` is a little long so we’ll first remove its non-essential parts.

▼ `rb_singleton_class()`

678 #define SPECIAL_SINGLETON(x,c) do {\

679 if (obj == (x)) {\

680 return c;\

681 }\

682 } while (0)

684 VALUE

685 rb_singleton_class(obj)

686 VALUE obj;

687 {

688 VALUE klass;

689

690 if (FIXNUM_P(obj) || SYMBOL_P(obj)) {

691 rb_raise(rb_eTypeError, “can’t define singleton”);

692 }

693 if (rb_special_const_p(obj)) {

694 SPECIAL_SINGLETON(Qnil, rb_cNilClass);

695 SPECIAL_SINGLETON(Qfalse, rb_cFalseClass);

696 SPECIAL_SINGLETON(Qtrue, rb_cTrueClass);

697 rb_bug(“unknown immediate %ld”, obj);

698 }

699

700 DEFER_INTS;

701 if (FL_TEST(RBASIC→klass, FL_SINGLETON) &&

702 (BUILTIN_TYPE(obj) == T_CLASS ||

703 rb_iv_get(RBASIC→klass, “attached”) == obj)) {

704 klass = RBASIC→klass;

705 }

706 else {

707 klass = rb_make_metaclass(obj, RBASIC→klass);

708 }

709 if (OBJ_TAINTED(obj)) {

710 OBJ_TAINT(klass);

711 }

712 else {

713 FL_UNSET(klass, FL_TAINT);

714 }

715 if (OBJ_FROZEN(obj)) OBJ_FREEZE(klass);

716 ALLOW_INTS;

717

718 return klass;

719 }

(class.c)

The first and the second half are separated by a blank line. The first half handles special cases and the second half handles the general case. In other words, the second half is the trunk of the function. That’s why we’ll keep it for later and talk about the first half.

Everything that is handled in the first half are non-pointer `VALUE`s, it means their object structs do not exist. First, `Fixnum` and `Symbol` are explicitly picked. Then, `rb_special_const_p()` is a function that returns true for non-pointer `VALUE`s, so there only `Qtrue`, `Qfalse` and `Qnil` should get caught. Other than that, there are no valid non-pointer `VALUE` so it would be reported as a bug with `rb_bug()`.

`DEFER_INTS()` and `ALLOW_INTS()` both end with the same `INTS` so you should see a pair in them. That’s the case, and they are macros related to signals. Because they are defined in `rubysig.h`, you can guess that `INTS` is the abbreviation of interrupts. You can ignore them.

Compressed `rb_make_metaclass()`

▼ `rb_make_metaclass()`

142 VALUE 143 rb_make_metaclass(obj, super) 144 VALUE obj, super; 145 { 146 VALUE klass = rb_class_boot(super); 147 FL_SET(klass, FL_SINGLETON); 148 RBASIC→klass = klass; 149 rb_singleton_class_attached(klass, obj); 150 if (BUILTIN_TYPE(obj) == T_CLASS) { 151 RBASIC→klass = klass; 152 if (FL_TEST(obj, FL_SINGLETON)) { 153 RCLASS→super = RBASIC→super))→klass; 154 } 155 } 156 157 return klass; 158 }(class.c)

We already saw `rb_class_boot()`. It creates a (normal) class using the `super` parameter as its superclass. After that, the `FL_SINGLETON` of this class is set. This is clearly suspicious. The name of the function makes us think that it is the indication of a singleton class.

What are singleton classes?

Finishing the above process, furthermore, we’ll through away the declarations because parameters, return values and local variables are all `VALUE`. That makes us able to compress to the following:

▼ `rb_singleton_class() rb_make_metaclass()` (after compression)

rb_singleton_class(obj)

{

if (FL_TEST(RBASIC→klass, FL_SINGLETON) &&

(BUILTIN_TYPE(obj) == T_CLASS || BUILTIN_TYPE(obj) == T_MODULE) &&

rb_iv_get(RBASIC→klass, “attached”) == obj) {

klass = RBASIC→klass;

}

else {

klass = rb_make_metaclass(obj, RBASIC→klass);

}

return klass;

}

rb_make_metaclass(obj, super)

{

klass = create a class with super as superclass;

FL_SET(klass, FL_SINGLETON);

RBASIC→klass = klass;

rb_singleton_class_attached(klass, obj);

if (BUILTIN_TYPE(obj) == T_CLASS) {

RBASIC→klass = klass;

if (FL_TEST(obj, FL_SINGLETON)) {

RCLASS→super =

RBASIC→super))→klass;

}

}

return klass;

}

The condition of the `if` statement of `rb_singleton_class()` seems quite complicated. However, this condition is not connected to `rb_make_metaclass()`, which is the mainstream, so we’ll see it later. Let’s first think about what happens on the false branch of the `if`.

The `BUILTIN_TYPE()` of `rb_make_metaclass()` is similar to `TYPE. That means this check in `rb_make_metaclass` means “if `obj` is a class”. For the moment we assume that `obj` is a class, so we’ll remove it.

With these simplifications, we get the following:

▼ `rb_singleton_class() rb_make_metaclass()` (after recompression)

rb_singleton_class(obj)

{

klass = create a class with RBASIC→klass as superclass;

FL_SET(klass, FL_SINGLETON);

RBASIC→klass = klass;

return klass;

}

But there is still a quite hard to understand side to it. That’s because `klass` is used too often. So let’s rename the `klass` variable to `sclass`.

▼ `rb_singleton_class() rb_make_metaclass()` (variable substitution)

rb_singleton_class(obj)

{

sclass = create a class with RBASIC→klass as superclass;

FL_SET(sclass, FL_SINGLETON);

RBASIC→klass = sclass;

return sclass;

}

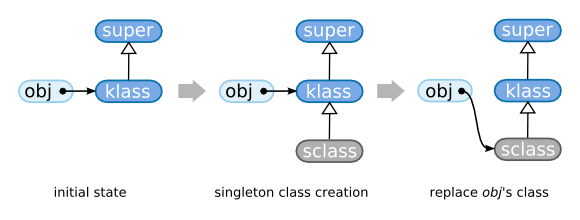

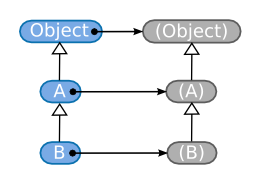

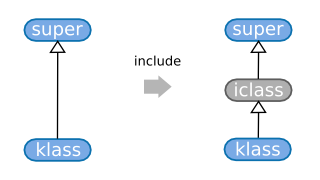

Now it should be very easy to understand. To make it even simpler, I’ve represented what is done with a diagram (figure 1). In the horizontal direction is the “instance – class” relation, and in the vertical direction is inheritance (the superclasses are above).

When comparing the first and last part of this diagram, you can understand that `sclass` is inserted without changing the structure. That’s all there is to singleton classes. In other words the inheritance is increased one step. By defining methods there, we can define methods which have completely nothing to do with other instances of `klass`.

Singleton classes and instances

By the way, did you notice about, during the compression process, the call to `rb_singleton_class_attached()` was stealthily removed? Here:

rb_make_metaclass(obj, super)

{

klass = create a class with super as superclass;

FL_SET(klass, FL_SINGLETON);

RBASIC(obj)->klass = klass;

rb_singleton_class_attached(klass, obj); /* THIS */

Let’s have a look at what it does.

▼ `rb_singleton_class_attached()`

130 void 131 rb_singleton_class_attached(klass, obj) 132 VALUE klass, obj; 133 { 134 if (FL_TEST(klass, FL_SINGLETON)) { 135 if (!RCLASS→iv_tbl) { 136 RCLASS→iv_tbl = st_init_numtable(); 137 } 138 st_insert(RCLASS→iv_tbl, rb_intern(“attached”), obj); 139 } 140 }(class.c)

If the `FL_SINGLETON` flag of `klass` is set… in other words if it’s a singleton class, put the `attached` → `obj` relation in the instance variable table of `klass` (`iv_tbl`). That’s how it looks like (in our case `klass` is always a singleton class… in other words its `FL_SINGLETON` flag is always set).

`attached` does not have the `@` prefix, but it’s stored in the instance variables table so it’s still an instance variable. Such an instance variable can never be read at the Ruby level so it can be used to keep values for the system’s exclusive use.

Let’s now think about the relationship between `klass` and `obj`. `klass` is the singleton class of `obj`. In other words, this “invisible” instance variable allows the singleton class to remember the instance it was created from. Its value is used when the singleton class is changed, notably to call hook methods on the instance (i.e. `obj`). For example, when a method is added to a singleton class, the `obj`‘s `singleton_method_added` method is called. There is no logical necessity to doing it, it was done because that’s how it was defined in the language.

But is it really all right? Storing the instance in `attached` will force one singleton class to have only one attached instance. For example, by getting (in some way or an other) the singleton class and calling `new` on it, won’t a singleton class end up having multiple instances?

This cannot be done because the proper checks are done to prevent the creation of an instance of a singleton class.

Singleton classes are in the first place for singleton methods. Singleton methods are methods existing only on a particular object. If singleton classes could have multiple instances, they would be the same as normal classes. Hence, each singleton class has only one instance … or rather, it must be limited to one.

Summary

We’ve done a lot, maybe made a real mayhem, so let’s finish and put everything in order with a summary.

What are singleton classes? They are classes that have the `FL_SINGLETON` flag set and that can only have one instance.

What are singleton methods? They are methods defined in the singleton class of an object.

Metaclasses

Inheritance of singleton methods

Infinite chain of classes

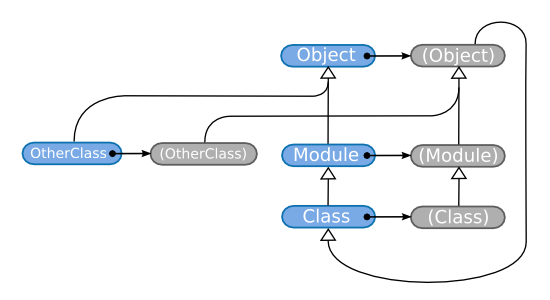

Even a class has a class, and it’s `Class`. And the class of `Class` is again `Class`. We find ourselves in an infinite loop (figure 2).

Up to here it’s something we’ve already gone through. What’s going after that is the theme of this chapter. Why do classes have to make a loop?

First, in Ruby all data are objects. And classes are data in Ruby so they have to be objects.

As they are objects, they must answer to methods. And setting the rule “to answer to methods you must belong to a class” made processing easier. That’s where comes the need for a class to also have a class.

Let’s base ourselves on this and think about the way to implement it. First, we can try first with the most naïve way, `Class`‘s class is `ClassClass`, `ClassClass`’s class is `ClassClassClass`…, chaining classes of classes one by one. But whichever the way you look at it, this can’t be implemented effectively. That’s why it’s common in object oriented languages where classes are objects that `Class`’s class is to `Class` itself, creating an endless virtual instance-class relationship.

((errata:

This structure is implemented efficiently in recent Ruby 1.8,

thus it can be implemented efficiently.

))

I’m repeating myself, but the fact that `Class`‘s class is `Class` is only to make the implementation easier, there’s nothing important in this logic.

“Class is also an object”

“Everything is an object” is often used as advertising statement when speaking about Ruby. And as a part of that, “Classes are also objects!” also appears. But these expressions often go too far. When thinking about these sayings, we have to split them in two:

- all data are objects

- classes are data

Talking about data or code makes a discussion much harder to understand. That’s why here we’ll restrict the meaning of “data” to “what can be put in variables in programs”.

Being able to manipulate classes from programs gives programs the ability to manipulate themselves. This is called reflection. In Ruby, which is a object oriented language and furthermore has classes, it is equivalent to be able to directly manipulate classes.

Nevertheless, there’s also a way in which classes are not objects. For example, there’s no problem in providing a feature to manipulate classes as function-style methods (functions defined at the top-level). However, as inside the interpreter there are data structures to represent the classes, it’s more natural in object oriented languages to make them available directly. And Ruby did this choice.

Furthermore, an objective in Ruby is for all data to be objects. That’s why it’s appropriate to make them objects.

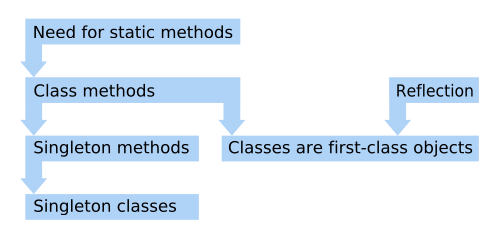

By the way, there is also a reason not linked to reflection why in Ruby classes had to be made objects. That is to prepare the place to define methods which are independent from instances (what are called static methods in Java and C++).

And to implement static methods, another thing was necessary: singleton methods. By chain reaction, that also makes singleton classes necessary. Figure 3 shows these dependency relationships.

Class methods inheritance

In Ruby, singleton methods defined in a class are called class methods. However, their specification is a little strange. For some reasons, class methods are inheritable.

class A

def A.test # defines a singleton method in A

puts("ok")

end

end

class B < A

end

B.test() # calls it

This can’t occur with singleton methods from objects that are not classes. In other words, classes are the only ones handled specially. In the following section we’ll see how class methods are inherited.

Singleton class of a class

Assuming that class methods are inherited, where is this operation done? It must be done either at class definition (creation) or at singleton method definition. Then let’s first look at the code defining classes.

Class definition means of course `rb_define_class()`. Now let’s take the call graph of this function.

rb_define_class

rb_class_inherited

rb_define_class_id

rb_class_new

rb_class_boot

rb_make_metaclass

rb_class_boot

rb_singleton_class_attached

If you’re wondering where you’ve seen it before, we looked at it in the previous section. At that time you did not see it but if you look closely, somehow `rb_make_metaclass()` appeared. As we saw before, this function introduces a singleton class. This is very suspicious. Why is this called even if we are not defining a singleton function? Furthermore, why is the lower level `rb_make_metaclass()` used instead of `rb_singleton_class()`? It looks like we have to check these surroundings again.

`rb_define_class_id()`

Let’s first start our reading with its caller, `rb_define_class_id()`.

▼ `rb_define_class_id()`

160 VALUE 161 rb_define_class_id(id, super) 162 ID id; 163 VALUE super; 164 { 165 VALUE klass; 166 167 if (!super) super = rb_cObject; 168 klass = rb_class_new(super); 169 rb_name_class(klass, id); 170 rb_make_metaclass(klass, RBASIC→klass); 171 172 return klass; 173 }(class.c)

`rb_class_new()` was a function that creates a class with `super` as its superclass. `rb_name_class()`‘s name means it names a class, but for the moment we do not care about names so we’ll skip it. After that there’s the `rb_make_metaclass()` in question. I’m concerned by the fact that when called from `rb_singleton_class()`, the parameters were different. Last time was like this:

rb_make_metaclass(obj, RBASIC(obj)->klass);

But this time is like this:

rb_make_metaclass(klass, RBASIC(super)->klass);

So as you can see it’s slightly different. How do the results change depending on that? Let’s have once again a look at a simplified `rb_make_metaclass()`.

`rb_make_metaclass` (once more)

▼ `rb_make_metaclass` (after first compression)

rb_make_metaclass(obj, super)

{

klass = create a class with super as superclass;

FL_SET(klass, FL_SINGLETON);

RBASIC→klass = klass;

rb_singleton_class_attached(klass, obj);

if (BUILTIN_TYPE(obj) == T_CLASS) {

RBASIC→klass = klass;

if (FL_TEST(obj, FL_SINGLETON)) {

RCLASS→super =

RBASIC→super))→klass;

}

}

return klass;

}

Last time, the `if` statement was wholly skipped, but looking once again, something is done only for `T_CLASS`, in other words classes. This clearly looks important. In `rb_define_class_id()`, as it’s called like this:

rb_make_metaclass(klass, RBASIC(super)->klass);

Let’s expand `rb_make_metaclass()`’s parameter variables with the actual values.

▼ `rb_make_metaclass` (recompression)

rb_make_metaclass(klass, super_klass /* == RBASIC→klass */) { sclass = create a class with super_class as superclass; RBASIC→klass = sclass; RBASIC→klass = sclass; return sclass; }

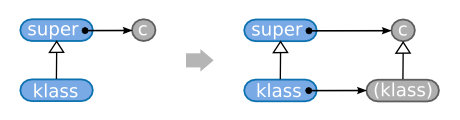

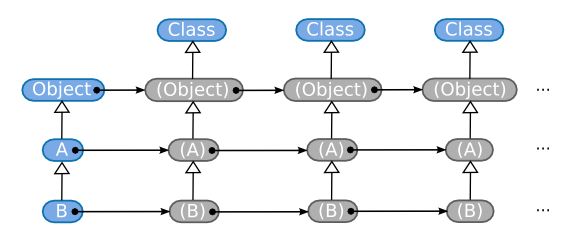

Doing this as a diagram gives something like figure 4. In it, the names between parentheses are singleton classes. This notation is often used in this book so I’d like you to remember it. This means that `obj`‘s singleton class is written as `(obj)`. And `(klass)` is the singleton class for `klass`. It looks like the singleton class is caught between a class and this class’s superclass’s class.

By expanding our imagination further from this result, we can think that the superclass’s class (the `c` in figure 4) must again be a singleton class. You’ll understand with one more inheritance level (figure 5).

As the relationship between `super` and `klass` is the same as the one between `klass` and `klass2`, `c` must be the singleton class `(super)`. If you continue like this, finally you’ll arrive at the conclusion that `Object`‘s class must be `(Object)`. And that’s the case in practice. For example, by inheriting like in the following program :

class A < Object end class B < A end

internally, a structure like figure 6 is created.

As classes and their metaclasses are linked and inherit like this, class methods are inherited.

Class of a class of a class

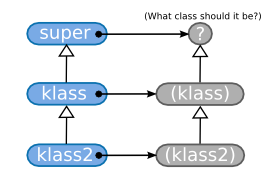

You’ve understood the working of class methods inheritance, but by doing that, in the opposite some questions have appeared. What is the class of a class’s singleton class? For this, we can check it by using debuggers. I’ve made figure 7 from the results of this investigation.

A class’s singleton class puts itself as its own class. Quite complicated.

The second question: the class of `Object` must be `Class`. Didn’t I properly confirm this in chapter 1: Ruby language minimum by using `class()` method?

p(Object.class()) # Class

Certainly, that’s the case “at the Ruby level”. But “at the C level”, it’s the singleton class `(Object)`. If `(Object)` does not appear at the Ruby level, it’s because `Object#class` skips the singleton classes. Let’s look at the body of the method, `rb_obj_class()` to confirm that.

▼ `rb_obj_class()`

86 VALUE 87 rb_obj_class(obj) 88 VALUE obj; 89 { 90 return rb_class_real(CLASS_OF(obj)); 91 } 76 VALUE 77 rb_class_real(cl) 78 VALUE cl; 79 { 80 while (FL_TEST(cl, FL_SINGLETON) || TYPE == T_ICLASS) { 81 cl = RCLASS→super; 82 } 83 return cl; 84 }(object.c)

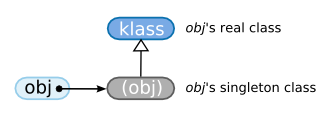

`CLASS_OF(obj)` returns the `basic.klass` of `obj`. While in `rb_class_real()`, all singleton classes are skipped (advancing towards the superclass). In the first place, singleton class are caught between a class and its superclass, like a proxy. That’s why when a “real” class is necessary, we have to follow the superclass chain (figure 8).

`I_CLASS` will appear later when we will talk about include.

Singleton class and metaclass

Well, the singleton classes that were introduced in classes is also one type of class, it’s a class’s class. So it can be called metaclass.

However, you should be wary of the fact that being a singleton class does not mean being a metaclass. The singleton classes introduced in classes are metaclasses. The important fact is not that they are singleton classes, but that they are the classes of classes. I was stuck on this point when I started learning Ruby. As I may not be the only one, I would like to make this clear.

Thinking about this, the `rb_make_metaclass()` function name is not very good. When used for a class, it does indeed create a metaclass, but when used for other objects, the created class is not a metaclass.

Then finally, even if you understood that some classes are metaclasses, it’s not as if there was any concrete gain. I’d like you not to care too much about it.

Bootstrap

We have nearly finished our talk about classes and metaclasses. But there is still one problem left. It’s about the 3 metaobjects `Object`, `Module` and `Class`. These 3 cannot be created with the common use API. To make a class, its metaclass must be built, but like we saw some time ago, the metaclass’s superclass is `Class`. However, as `Class` has not been created yet, the metaclass cannot be build. So in `ruby`, only these 3 classes’s creation is handled specially.

Then let’s look at the code:

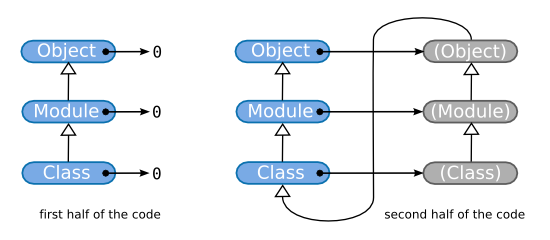

▼ `Object`, `Module` and `Class` creation

1243 rb_cObject = boot_defclass(“Object”, 0); 1244 rb_cModule = boot_defclass(“Module”, rb_cObject); 1245 rb_cClass = boot_defclass(“Class”, rb_cModule); 1246 1247 metaclass = rb_make_metaclass(rb_cObject, rb_cClass); 1248 metaclass = rb_make_metaclass(rb_cModule, metaclass); 1249 metaclass = rb_make_metaclass(rb_cClass, metaclass);(object.c)

First, in the first half, `boot_defclass()` is similar to `rb_class_boot()`, it just creates a class with its given superclass set. These links give us something like the left part of figure 9.

And in the three lines of the second half, `(Object)`, `(Module)` and `(Class)` are created and set (right figure 9). `(Object)` and `(Module)`‘s classes… that is themselves… is already set in `rb_make_metaclass()` so there is no problem. With this, the metaobjects’ bootstrap is finished.

After taking everything into account, it gives us the final shape like figure 10.

Class names

In this section, we will analyse how’s formed the reciprocal conversion between class and class names, in other words constants. Concretely, we will target `rb_define_class()` and `rb_define_class_under()`.

Name → class

First we’ll read `rb_defined_class()`. After the end of this function, the class can be found from the constant.

▼ `rb_define_class()`

183 VALUE 184 rb_define_class(name, super) 185 const char name; 186 VALUE super; 187 { 188 VALUE klass; 189 ID id; 190 191 id = rb_intern(name); 192 if (rb_autoload_defined(id)) { / (A) autoload / 193 rb_autoload_load(id); 194 } 195 if (rb_const_defined(rb_cObject, id)) { / (B) rb_const_defined / 196 klass = rb_const_get(rb_cObject, id); / © rb_const_get / 197 if (TYPE != T_CLASS) { 198 rb_raise(rb_eTypeError, “%s is not a class”, name); 199 } / (D) rb_class_real */ 200 if (rb_class_real(RCLASS→super) != super) { 201 rb_name_error(id, “%s is already defined”, name); 202 } 203 return klass; 204 } 205 if (!super) { 206 rb_warn(“no super class for ‘%s’, Object assumed”, name); 207 } 208 klass = rb_define_class_id(id, super); 209 rb_class_inherited(super, klass); 210 st_add_direct(rb_class_tbl, id, klass); 211 212 return klass; 213 }(class.c)

This can be clearly divided into the two parts: before and after `rb_define_class_id()`. The former is to acquire or create the class. The latter is to assign it to the constant. We will look at it in more detail below.

(A) In Ruby, there is a feature named autoload that automatically loads libraries when certain constants are accessed. These functions named `rb_autoload_xxxx()` are for its checks. You can ignore it without any problem.

(B) We determine whether the `name` constant has been defined or not in `Object`.

(C) Get the value of the `name` constant. This will be explained in detail in chapter 6.

(D) We’ve seen `rb_class_real()` some time ago. If the class `c` is a singleton class or an `ICLASS`, it climbs the `super` hierarchy up to a class that is not and returns it. In short, this function skips the virtual classes that should not appear at the Ruby level.

That’s what we can read nearby.

As constants are involved around this, it is very troublesome. But I feel like the chapter about constants is probably not so right place to talk about class definition, that’s the reason of such halfway description around here.

Moreover, about this coming after `rb_define_class_id()`,

st_add_direct(rb_class_tbl, id, klass);

This part assigns the class to the constant. However, whichever way you look at it you do not see that. In fact, top-level classes and modules that are defined in C are separated from the other constants and regrouped in `rb_class_tbl()`. The split is slightly related to the GC. It’s not essential.

Class → name

We understood how the class can be obtained from the class name, but how to do the opposite? By doing things like calling `p` or `Class#name`, we can get the name of the class, but how is it implemented?

In fact this is done by `rb_name_class()` which already appeared a long time ago. The call is around the following:

rb_define_class

rb_define_class_id

rb_name_class

Let’s look at its content:

▼ `rb_name_class()`

269 void 270 rb_name_class(klass, id) 271 VALUE klass; 272 ID id; 273 { 274 rb_iv_set(klass, “classid”, ID2SYM); 275 }(variable.c)

`classid` is another instance variable that can’t be seen from Ruby. As only `VALUE`s can be put in the instance variable table, the `ID` is converted to `Symbol` using `ID2SYM()`.

That’s how we are able to find the constant name from the class.

Nested classes

So, in the case of classes defined at the top-level, we know how works the reciprocal link between name and class. What’s left is the case of classes defined in modules or other classes, and for that it’s a little more complicated. The function to define these nested classes is `rb_define_class_under()`.

▼ `rb_define_class_under()`

215 VALUE 216 rb_define_class_under(outer, name, super) 217 VALUE outer; 218 const char *name; 219 VALUE super; 220 { 221 VALUE klass; 222 ID id; 223 224 id = rb_intern(name); 225 if (rb_const_defined_at(outer, id)) { 226 klass = rb_const_get(outer, id); 227 if (TYPE != T_CLASS) { 228 rb_raise(rb_eTypeError, “%s is not a class”, name); 229 } 230 if (rb_class_real(RCLASS→super) != super) { 231 rb_name_error(id, “%s is already defined”, name); 232 } 233 return klass; 234 } 235 if (!super) { 236 rb_warn(“no super class for ‘%s::%s’, Object assumed”, 237 rb_class2name(outer), name); 238 } 239 klass = rb_define_class_id(id, super); 240 rb_set_class_path(klass, outer, name); 241 rb_class_inherited(super, klass); 242 rb_const_set(outer, id, klass); 243 244 return klass; 245 }(class.c)

The structure is like the one of `rb_define_class()`: before the call to `rb_define_class_id()` is the redefinition check, after is the creation of the reciprocal link between constant and class. The first half is pretty boringly similar to `rb_define_class()` so we’ll skip it. In the second half, `rb_set_class_path()` is new. We’re going to look at it.

`rb_set_class_path()`

This function gives the name `name` to the class `klass` nested in the class `under`. “class path” means a constant name including all the nesting information starting from top-level, for example “`Net::NetPrivate::Socket`”.

▼ `rb_set_class_path()`

210 void 211 rb_set_class_path(klass, under, name) 212 VALUE klass, under; 213 const char name; 214 { 215 VALUE str; 216 217 if (under == rb_cObject) { / defined at top-level / 218 str = rb_str_new2(name); / create a Ruby string from name / 219 } 220 else { / nested constant / 221 str = rb_str_dup(rb_class_path(under)); / copy the return value / 222 rb_str_cat2(str, “::”); / concatenate “::” / 223 rb_str_cat2(str, name); / concatenate name */ 224 } 225 rb_iv_set(klass, “classpath”, str); 226 }(variable.c)

Everything except the last line is the construction of the class path, and the last line makes the class remember its own name. `classpath` is of course another instance variable that can’t be seen from a Ruby program. In `rb_name_class()` there was `classid`, but `id` is different because it does not include nesting information (look at the table below).

__classpath__ Net::NetPrivate::Socket __classid__ Socket

It means classes defined for example in `rb_defined_class()` all have `classid` or `classpath` defined. So to find `under`‘s classpath we can look up in these instance variables. This is done by `rb_class_path()`. We’ll omit its content.

Nameless classes

Contrary to what I have just said, there are in fact cases in which neither `classpath` nor `classid` are set. That is because in Ruby you can use a method like the following to create a class.

c = Class.new()

If a class is created like this, it won’t go through `rb_define_class_id()` and the classpath won’t be set. In this case, `c` does not have any name, which is to say we get an unnamed class.

However, if later it’s assigned to a constant, a name will be attached to the class at that moment.

SomeClass = c # the class name is SomeClass

Strictly speaking, at the first time requesting the name after assigning it to a constant, the name will be attached to the class. For instance, when calling `p` on this `SomeClass` class or when calling the `Class#name` method. When doing this, a value equal to the class is searched in `rb_class_tbl`, and a name has to be chosen. The following case can also happen:

class A

class B

C = tmp = Class.new()

p(tmp) # here we search for the name

end

end

so in the worst case we have to search for the whole constant space. However, generally, there aren’t many constants so even searching all constants does not take too much time.

Include

We only talked about classes so let’s finish this chapter with something else and talk about module inclusion.

`rb_include_module` (1)

Includes are done by the ordinary method `Module#include`. Its corresponding function in C is `rb_include_module()`. In fact, to be precise, its body is `rb_mod_include()`, and there `Module#append_feature` is called, and this function’s default implementation finally calls `rb_include_module()`. Mixing what’s happening in Ruby and C gives us the following call graph.

Module#include (rb_mod_include)

Module#append_features (rb_mod_append_features)

rb_include_module

Anyway, the manipulations that are usually regarded as inclusions are done by `rb_include_module()`. This function is a little long so we’ll look at it a half at a time.

▼ `rb_include_module` (first half)

/* include module in class */

347 void

348 rb_include_module(klass, module)

349 VALUE klass, module;

350 {

351 VALUE p, c;

352 int changed = 0;

353

354 rb_frozen_class_p(klass);

355 if (!OBJ_TAINTED(klass)) {

356 rb_secure(4);

357 }

358

359 if (NIL_P(module)) return;

360 if (klass == module) return;

361

362 switch (TYPE) {

363 case T_MODULE:

364 case T_CLASS:

365 case T_ICLASS:

366 break;

367 default:

368 Check_Type(module, T_MODULE);

369 }

(class.c)

For the moment it’s only security and type checking, therefore we can ignore it. The process itself is below:

▼ `rb_include_module` (second half)

371 OBJ_INFECT(klass, module);

372 c = klass;

373 while (module) {

374 int superclass_seen = Qfalse;

375

376 if (RCLASS→m_tbl == RCLASS→m_tbl)

377 rb_raise(rb_eArgError, “cyclic include detected”);

378 /* (A) skip if the superclass already includes module /

379 for (p = RCLASS→super; p; p = RCLASS→super) {

380 switch (BUILTIN_TYPE(p)) {

381 case T_ICLASS:

382 if (RCLASS→m_tbl == RCLASS→m_tbl) {

383 if (!superclass_seen) {

384 c = p; / move the insertion point */

385 }

386 goto skip;

387 }

388 break;

389 case T_CLASS:

390 superclass_seen = Qtrue;

391 break;

392 }

393 }

394 c = RCLASS→super =

include_class_new(module, RCLASS→super);

395 changed = 1;

396 skip:

397 module = RCLASS→super;

398 }

399 if (changed) rb_clear_cache();

400 }

(class.c)

First, what the (A) block does is written in the comment. It seems to be a special condition so let’s first skip reading it for now. By extracting the important parts from the rest we get the following:

c = klass;

while (module) {

c = RCLASS(c)->super = include_class_new(module, RCLASS(c)->super);

module = RCLASS(module)->super;

}

In other words, it’s a repetition of `module`‘s `super`. What is in `module`’s `super` must be a module included by `module` (because our intuition tells us so). Then the superclass of the class where the inclusion occurs is replaced with something. We do not understand much what, but at the moment I saw that I felt “Ah, doesn’t this look the addition of elements to a list (like LISP’s cons)?” and it suddenly make the story faster. In other words it’s the following form:

list = new(item, list)

Thinking about this, it seems we can expect that module is inserted between `c` and `c→super`. If it’s like this, it fits module’s specification.

But to be sure of this we have to look at `include_class_new()`.

`include_class_new()`

▼ `include_class_new()`

319 static VALUE 320 include_class_new(module, super) 321 VALUE module, super; 322 { 323 NEWOBJ; /* (A) / 324 OBJSETUP; 325 326 if (BUILTIN_TYPE(module) == T_ICLASS) { 327 module = RBASIC→klass; 328 } 329 if (!RCLASS→iv_tbl) { 330 RCLASS→iv_tbl = st_init_numtable(); 331 } 332 klass→iv_tbl = RCLASS→iv_tbl; / (B) / 333 klass→m_tbl = RCLASS→m_tbl; 334 klass→super = super; / © / 335 if (TYPE == T_ICLASS) { / (D) / 336 RBASIC→klass = RBASIC→klass; / (D-1) / 337 } 338 else { 339 RBASIC→klass = module; / (D-2) */ 340 } 341 OBJ_INFECT(klass, module); 342 OBJ_INFECT(klass, super); 343 344 return (VALUE)klass; 345 }(class.c)

We’re lucky there’s nothing we do not know.

(A) First create a new class.

(B) Transplant `module`’s instance variable and method tables into this class.

(C) Make the including class’s superclass (`super`) the super class of this new class.

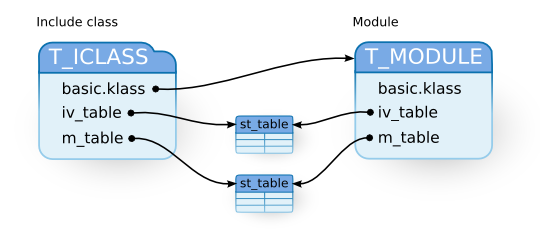

In other words, it looks like this function creates an include class which we can regard it as something like an “avatar” of the `module`. The important point is that at (B) only the pointer is moved on, without duplicating the table. Later, if a method is added, the module’s body and the include class will still have exactly the same methods (figure 11).

If you look closely at (A), the structure type flag is set to T_ICLASS. This seems to be the mark of an include class. This function’s name is `include_class_new()` so `ICLASS`’s `I` must be `include`.

And if you think about joining what this function and `rb_include_module()` do, we know that our previous expectations were not wrong. In brief, including is inserting the include class of a module between a class and its superclass (figure 12).

At (D-2) the module is stored in the include class’s `klass`. At (D-1), the module’s body is taken out… I’d like to say so if possible, but in fact this check does not have any use. The `T_ICLASS` check is already done at the beginning of this function, so when arriving here there can’t still be a `T_ICLASS`. Modification to `ruby` piled up at piece by piece during quite a long period of time so there are quite a few small overlooks.

There is one more thing to consider. Somehow the include class’s `basic.klass` is only used to point to the module’s body, so for example calling a method on the include class would be very bad. So include classes must not be seen from Ruby programs. And in practice all methods skip include classes, with no exception.

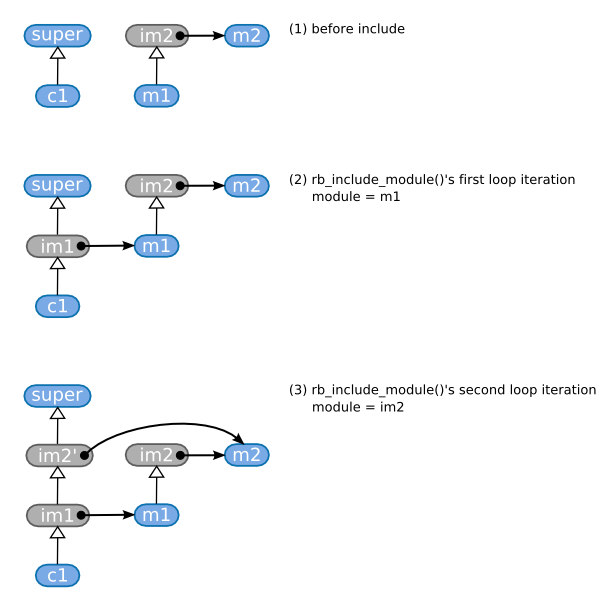

Simulation

It was complicated so let’s look at a concrete example. I’d like you to look at figure 13 (1). We have the `c1` class and the `m1` module that includes `m2`. From there, the changes made to include `m1` in `c1` are (2) and (3). `im`s are of course include classes.

`rb_include_module` (2)

Well, now we can explain the part of `rb_include_module()` we skipped.

▼ `rb_include_module` (avoiding double inclusion)

378 /* (A) skip if the superclass already includes module / 379 for (p = RCLASS→super; p; p = RCLASS→super) { 380 switch (BUILTIN_TYPE(p)) { 381 case T_ICLASS: 382 if (RCLASS→m_tbl == RCLASS→m_tbl) { 383 if (!superclass_seen) { 384 c = p; / the inserting point is moved */ 385 } 386 goto skip; 387 } 388 break; 389 case T_CLASS: 390 superclass_seen = Qtrue; 391 break; 392 } 393 }(class.c)

Among the superclasses of the klass (`p`), if a `p` is `T_ICLASS` (an include class) and has the same method table as the one of the module we want to include (`module`), it means that the `p` is an include class of the `module`. Therefore, it would be skipped to not include the module twice. However, if this module includes another module (`module→super`), It would be checked once more.

But, because `p` is a module that has been included once, the modules included by it must also already be included… that’s what I thought for a moment, but we can have the following context:

module M end module M2 end class C include M # M2 is not yet included in M end # therefore M2 is not in C's superclasses module M include M2 # as there M2 is included in M, end class C include M # I would like here to only add M2 end

To say this conversely, there are cases that a result of `include` is not propagated soon.

For class inheritance, the class’s singleton methods were inherited but in the case of module there is no such thing. Therefore the singleton methods of the module are not inherited by the including class (or module). When you want to also inherit singleton methods, the usual way is to override `Module#append_features`.