Ruby Hacking Guide

Translated by Peter Zotov

I’m very grateful to my employer Evil Martians , who sponsored

the work, and Nikolay Konovalenko , who put

more effort in this translation than I could ever wish for. Without them,

I would be still figuring out what `COND_LEXPOP()` actually does.

Chapter 11 Finite-state scanner

Outline

In theory, the scanner and the parser are completely independent of each other – the scanner is supposed to recognize tokens, while the parser is supposed to process the resulting series of tokens. It would be nice if things were that simple, but in reality it rarely is. Depending on the context of the program it is often necessary to alter the way tokens are recognized or their symbols. In this chapter we will take a look at the way the scanner and the parser cooperate.

Practical examples

In most programming languages, spaces don’t have any specific meaning unless they are used to separate words. However, Ruby is not an ordinary language and meanings can change significantly depending on the presence of spaces. Here is an example

a[i] = 1 # a[i] = (1) a [i] # a([i])

The former is an example of assigning an index. The latter is an example of omitting the method call parentheses and passing a member of an array to a parameter.

Here is another example.

a + 1 # (a) + (1) a +1 # a(+1)

This seems to be really disliked by some.

However, the above examples might give one the impression that only omitting the method call parentheses can be a source of trouble. Let’s look at a different example.

`cvs diff parse.y` # command call string

obj.`("cvs diff parse.y") # normal method call

Here, the former is a method call using a literal. In contrast, the latter is a normal method call (with ‘’’ being the method name). Depending on the context, they could be handled quite differently.

Below is another example where the functioning changes dramatically

print(<<EOS) # here-document ...... EOS list = [] list << nil # list.push(nil)

The former is a method call using a here-document. The latter is a method call using an operator.

As demonstrated, Ruby’s grammar contains many parts which are difficult to implement in practice. I couldn’t realistically give a thorough description of all in just one chapter, so in this one I will look at the basic principles and those parts which present the most difficulty.

`lex_state`

There is a variable called “lex_state”. “lex”, obviously, stands for “lexer”. Thus, it is a variable which shows the scanner’s state.

What states are there? Let’s look at the definitions.

▼ `enum lex_state`

61 static enum lex_state {

62 EXPR_BEG, /* ignore newline, +/- is a sign. /

63 EXPR_END, / newline significant, +/- is a operator. /

64 EXPR_ARG, / newline significant, +/- is a operator. /

65 EXPR_CMDARG, / newline significant, +/- is a operator. /

66 EXPR_ENDARG, / newline significant, +/- is a operator. /

67 EXPR_MID, / newline significant, +/- is a operator. /

68 EXPR_FNAME, / ignore newline, no reserved words. /

69 EXPR_DOT, / right after `.’ or `::‘, no reserved words. /

70 EXPR_CLASS, / immediate after `class’, no here document. */

71 } lex_state;

(parse.y)

The EXPR prefix stands for “expression”. `EXPR_BEG` is “Beginning of expression” and `EXPR_DOT` is “inside the expression, after the dot”.

To elaborate, `EXPR_BEG` denotes “Located at the head of the expression”. `EXPR_END` denotes “Located at the end of the expression”. `EXPR_ARG` denotes “Before the method parameter”. `EXPR_FNAME` denotes “Before the method name (such as `def`)”. The ones not covered here will be analyzed in detail below.

Incidentally, I am led to believe that `lex_state` actually denotes “after parentheses”, “head of statement”, so it shows the state of the parser rather than the scanner. However, it’s still conventionally referred to as the scanner’s state and here’s why.

The meaning of “state” here is actually subtly different from how it’s usually understood. The “state” of `lex_state` is “a state under which the scanner does x”. For example an accurate description of `EXPR_BEG` would be “A state under which the scanner, if run, will react as if this is at the head of the expression”

Technically, this “state” can be described as the state of the scanner if we look at the scanner as a state machine. However, delving there would be veering off topic and too tedious. I would refer any interested readers to any textbook on data structures.

Understanding the finite-state scanner

The trick to reading a finite-state scanner is to not try to grasp everything at once. Someone writing a parser would prefer not to use a finite-state scanner. That is to say, they would prefer not to make it the main part of the process. Scanner state management often ends up being an extra part attached to the main part. In other words, there is no such thing as a clean and concise diagram for state transitions.

What one should do is think toward specific goals: “This part is needed to solve this task” “This code is for overcoming this problem”. Basically, put out code in accordance with the task at hand. If you start thinking about the mutual relationship between tasks, you’ll invariably end up stuck. Like I said, there is simply no such thing.

However, there still needs to be an overreaching objective. When reading a finite-state scanner, that objective would undoubtedly be to understand every state. For example, what kind of state is `EXPR_BEG`? It is a state where the parser is at the head of the expression.

The static approach

So, how can we understand what a state does? There are three basic approaches

- Look at the name of the state

The simplest and most obvious approach. For example, the name `EXPR_BEG` obviously refers to the head (beginning) of something.

- Observe what changes under this state

Look at the way token recognition changes under the state, then test it in comparison to previous examples.

- Look at the state from which it transitions

Look at which state it transitions from and which token causes it. For example, if `‘\n’` is always followed by a transition to a `HEAD` state, it must denote the head of the line.

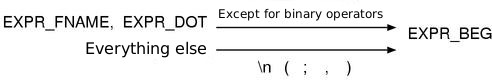

Let us take `EXPR_BEG` as an example. In Ruby, all state transitions are expressed as assignments to `lex_state`, so first we need to grep `EXPR_BEG` assignments to find them. Then we need to export their location, for example, such as `‘#’` and `‘*’` and `‘!’` of `yylex()` Then we need to recall the state prior to the transition and consider which case suits best (see image 1)

((errata:

1. Actually when the state is `EXPR_DOT`, the state after reading a

`tIDENTIFIER` would be either `ARG` or `CMDARG`.

However, because the author wanted to roughly group them as `FNAME/DOT` and the

others here, these two are shown together.

Therefore, to be precise, `EXPR_FNAME` and `EXPR_DOT` should have also been

separated.

2. ‘`)`’ does not cause the transition from “everything else” to `EXPR_BEG`.

))

This does indeed look like the head of statement. Especially the `‘\n’` and the `‘;’` The open parentheses and the comma also suggest that it’s the head not just of the statement, but of the expression as well.

The dynamic approach

There are other easy methods to observe the functioning. For example, you can use a debugger to “hook” the `yylex()` and look at the `lex_state`

Another way is to rewrite the source code to output state transitions. In the case of `lex_state` we only have a few patterns for assignment and comparison, so the solution would be to grasp them as text patterns and rewrite the code to output state transitions. The CD that comes with this book contains the `rubylex-analyser` tool. When necessary, I will refer to it in this text.

The overall process looks like this: use a debugger or the aforementioned tool to observe the functioning of the program. Then look at the source code to confirm the acquired data and use it.

Description of states

Here I will give simple descriptions of `lex_state` states.

- `EXPR_BEG`

Head of expression. Comes immediately after `\n ( { [ ! ? : ,` or the operator `op=` The most general state.

- `EXPR_MID`

Comes immediately after the reserved words `return break next rescue`. Invalidates binary operators such as `*` or `&` Generally similar in function to `EXPR_BEG`

- `EXPR_ARG`

Comes immediately after elements which are likely to be the method name in a method call. Also comes immediately after `‘[’` Except for cases where `EXPR_CMDARG` is used.

- `EXPR_CMDARG`

Comes before the first parameter of a normal method call. For more information, see the section “The `do` conflict”

- `EXPR_END`

Used when there is a possibility that the statement is terminal. For example, after a literal or a closing parenthesis. Except for cases when `EXPR_ENDARG` is used

- `EXPR_ENDARG`

Special iteration of `EXPR_END` Comes immediately after the closing parenthesis corresponding to `tLPAREN_ARG` Refer to the section “First parameter enclosed in parentheses”

- `EXPR_FNAME`

Comes before the method name, usually after `def`, `alias`, `undef` or the

symbol `‘:’` A single “`” can be a name.

- `EXPR_DOT`

Comes after the dot in a method call. Handled similarly to `EXPR_FNAME`

Various reserved words are treated as simple identifiers.

A single '`' can be a name.

- `EXPR_CLASS`

Comes after the reserved word `class` This is a very limited state.

The following states can be grouped together

- `BEG MID`

- `END ENDARG`

- `ARG CMDARG`

- `FNAME DOT`

They all express similar conditions. `EXPR_CLASS` is a little different, but only appears in a limited number of places, not warranting any special attention.

Line-break handling

The problem

In Ruby, a statement does not necessarily require a terminator. In C or Java a statement must always end with a semicolon, but Ruby has no such requirement. Statements usually take up only one line, and thus end at the end of the line.

On the other hand, when a statement is clearly continued, this happens automatically. Some conditions for “This statement is clearly continued” are as follows:

- After a comma

- After an infix operator

- Parentheses or brackets are not balanced

- Immediately after the reserved word `if`

Etc.

Implementation

So, what do we need to implement this grammar? Simply having the scanner ignore line-breaks is not sufficient. In a grammar like Ruby’s, where statements are delimited by reserved words on both ends, conflicts don’t happen as frequently as in C languages, but when I tried a simple experiment, I couldn’t get it to work until I got rid of `return` `next` `break` and returned the method call parentheses wherever they were omitted. To retain those features we need some kind of terminal symbol for statements’ ends. It doesn’t matter whether it’s `\n` or `‘;’` but it is necessary.

Two solutions exist – parser-based and scanner-based. For the former, you can just optionally put `\n` in every place that allows it. For the latter, have the `\n` passed to the parser only when it has some meaning (ignoring it otherwise).

Which solution to use is up to your preferences, but usually the scanner-based one is used. That way produces a more compact code. Moreover, if the rules are overloaded with meaningless symbols, it defeats the purpose of the parser-generator.

To sum up, in Ruby, line-breaks are best handled using the scanner. When a line needs to continued, the `\n` will be ignored, and when it needs to be terminated, the `\n` is passed as a token. In the `yylex()` this is found here:

▼ `yylex()`-`‘\n’`

3155 case ‘\n’:

3156 switch (lex_state) {

3157 case EXPR_BEG:

3158 case EXPR_FNAME:

3159 case EXPR_DOT:

3160 case EXPR_CLASS:

3161 goto retry;

3162 default:

3163 break;

3164 }

3165 command_start = Qtrue;

3166 lex_state = EXPR_BEG;

3167 return ‘\n’;

(parse.y)

With `EXPR_BEG`, `EXPR_FNAME`, `EXPR_DOT`, `EXPR_CLASS` it will be `goto retry`. That is to say, it’s meaningless and shall be ignored. The label `retry` is found in front of the large `switch` in the `yylex()`

In all other instances, line-breaks are meaningful and shall be passed to the parser, after which `lex_state` is restored to `EXPR_BEG` Basically, whenever a line-break is meaningful, it will be the end of `expr`

I recommend leaving `command_start` alone for the time being. To reiterate, trying to grasp too many things at once will only end in needless confusion.

Let us now take a look at some examples using the `rubylex-analyser` tool.

% rubylex-analyser -e '

m(a,

b, c) unless i

'

+EXPR_BEG

EXPR_BEG C "\nm" tIDENTIFIER EXPR_CMDARG

EXPR_CMDARG "(" '(' EXPR_BEG

0:cond push

0:cmd push

EXPR_BEG C "a" tIDENTIFIER EXPR_CMDARG

EXPR_CMDARG "," ',' EXPR_BEG

EXPR_BEG S "\n b" tIDENTIFIER EXPR_ARG

EXPR_ARG "," ',' EXPR_BEG

EXPR_BEG S "c" tIDENTIFIER EXPR_ARG

EXPR_ARG ")" ')' EXPR_END

0:cond lexpop

0:cmd lexpop

EXPR_END S "unless" kUNLESS_MOD EXPR_BEG

EXPR_BEG S "i" tIDENTIFIER EXPR_ARG

EXPR_ARG "\n" \n EXPR_BEG

EXPR_BEG C "\n" ' EXPR_BEG

As you can see, there is a lot of output here, but we only need the left and middle columns. The left column displays the `lex_state` before it enters the `yylex()` while the middle column displays the tokens and their symbols.

The first token `m` and the second parameter `b` are preceded by a line-break but a `\n` is appended in front of them and it is not treated as a terminal symbol. That is because the `lex_state` is `EXPR_BEG`.

However, in the second to last line `\n` is used as a terminal symbol. That is because the state is `EXPR_ARG`

And that is how it should be used. Let us have another example.

% rubylex-analyser -e 'class C < Object end' +EXPR_BEG EXPR_BEG C "class" kCLASS EXPR_CLASS EXPR_CLASS "\nC" tCONSTANT EXPR_END EXPR_END S "<" '<' EXPR_BEG +EXPR_BEG EXPR_BEG S "Object" tCONSTANT EXPR_ARG EXPR_ARG "\n" \n EXPR_BEG EXPR_BEG C "end" kEND EXPR_END EXPR_END "\n" \n EXPR_BEG

The reserved word `class` is followed by `EXPR_CLASS` so the line-break is ignored. However, the superclass `Object` is followed by `EXPR_ARG`, so the `\n` appears.

% rubylex-analyser -e 'obj. class' +EXPR_BEG EXPR_BEG C "obj" tIDENTIFIER EXPR_CMDARG EXPR_CMDARG "." '.' EXPR_DOT EXPR_DOT "\nclass" tIDENTIFIER EXPR_ARG EXPR_ARG "\n" \n EXPR_BEG

`‘.’` is followed by `EXPR_DOT` so the `\n` is ignored.

Note that `class` becomes `tIDENTIFIER` despite being a reserved word. This is discussed in the next section.

Reserved words and identical method names

The problem

In Ruby, reserved words can used as method names. However, in actuality it’s not as simple as “it can be used” – there exist three possible contexts:

- Method definition (`def xxxx`)

- Call (`obj.xxxx`)

- Symbol literal (`:xxxx`)

All three are possible in Ruby. Below we will take a closer look at each.

First, the method definition. It is preceded by the reserved word `def` so it should work.

In case of the method call, omitting the receiver can be a source of difficulty. However, the scope of use here is even more limited, and omitting the receiver is actually forbidden. That is, when the method name is a reserved word, the receiver absolutely cannot be omitted. Perhaps it would be more accurate to say that it is forbidden in order to guarantee that parsing is always possible.

Finally, in case of the symbol, it is preceded by the terminal symbol `‘:’` so it also should work. However, regardless of reserved words, the `‘:’` here conflicts with the colon in `a?b:c` If this is avoided, there should be no further trouble.

For each of these cases, similarly to before, a scanner-based solution and a parser-based solution exist. For the former use `tIDENTIFIER` (for example) as the reserved word that comes after `def` or `.` or `:` For the latter, make that into a rule. Ruby allows for both solutions to be used in each of the three cases.

Method definition

The name part of the method definition. This is handled by the parser.

▼ Method definition rule

| kDEF fname f_arglist bodystmt kEND | kDEF singleton dot_or_colon fname f_arglist bodystmt kEND

There exist only two rules for method definition – one for normal methods and one for singleton methods. For both, the name part is `fname` and it is defined as follows.

▼ `fname`

fname : tIDENTIFIER | tCONSTANT | tFID | op | reswords

`reswords` is a reserved word and `op` is a binary operator. Both rules consist of simply all terminal symbols lined up, so I won’t go into detail here. Finally, for `tFID` the end contains symbols similarly to `gsub!` and `include?`

Method call

Method calls with names identical to reserved words are handled by the scanner. The scan code for reserved words is shown below.

Scanning the identifier

result = (tIDENTIFIER or tCONSTANT)

if (lex_state != EXPR_DOT) {

struct kwtable *kw;

/* See if it is a reserved word. */

kw = rb_reserved_word(tok(), toklen());

Reserved word is processed

}

`EXPR_DOT` expresses what comes after the method call dot. Under `EXPR_DOT` reserved words are universally not processed. The symbol for reserved words after the dot becomes either `tIDENTIFIER` or `tCONSTANT`.

Symbols

Reserved word symbols are handled by both the scanner and the parser. First, the rule.

▼ `symbol`

symbol : tSYMBEG symsym : fname | tIVAR | tGVAR | tCVAR

fname : tIDENTIFIER | tCONSTANT | tFID | op | reswords

Reserved words (`reswords`) are explicitly passed through the parser. This is only possible because the special terminal symbol `tSYMBEG` is present at the start. If the symbol were, for example, `‘:’` it would conflict with the conditional operator (`a?b:c`) and stall. Thus, the trick is to recognize `tSYMBEG` on the scanner level.

But how to cause that recognition? Let’s look at the implementation of the scanner.

▼ `yylex`-`‘:’`

3761 case ‘:’:

3762 c = nextc();

3763 if (c == ‘:’) {

3764 if (lex_state == EXPR_BEG || lex_state == EXPR_MID ||

3765 (IS_ARG() && space_seen)) {

3766 lex_state = EXPR_BEG;

3767 return tCOLON3;

3768 }

3769 lex_state = EXPR_DOT;

3770 return tCOLON2;

3771 }

3772 pushback©;

3773 if (lex_state == EXPR_END ||

lex_state == EXPR_ENDARG ||

ISSPACE©) {

3774 lex_state = EXPR_BEG;

3775 return ‘:’;

3776 }

3777 lex_state = EXPR_FNAME;

3778 return tSYMBEG;

(parse.y)

This is a situation when the `if` in the first half has two consecutive `‘:’` In this situation, the `‘::’`is scanned in accordance with the leftmost longest match basic rule.

For the next `if` , the `‘:’` is the aforementioned conditional operator. Both `EXPR_END` and `EXPR_ENDARG` come at the end of the expression, so a parameter does not appear. That is to say, since there can’t be a symbol, the `‘:’` is a conditional operator. Similarly, if the next letter is a space (`ISSPACE`) , a symbol is unlikely so it is again a conditional operator.

When none of the above applies, it’s all symbols. In that case, a transition to `EXPR_FNAME` occurs to prepare for all method names. There is no particular danger to parsing here, but if this is forgotten, the scanner will not pass values to reserved words and value calculation will be disrupted.

Modifiers

The problem

For example, for `if` if there exists a normal notation and one for postfix modification.

# Normal notation if cond then expr end # Postfix expr if cond

This could cause a conflict. The reason can be guessed – again, it’s because method parentheses have been omitted previously. Observe this example

call if cond then a else b end

Reading this expression up to the `if` gives us two possible interpretations.

call((if ....)) call() if ....

When unsure, I recommend simply using trial and error and seeing if a conflict occurs. Let us try to handle it with `yacc` after changing `kIF_MOD` to `kIF` in the grammar.

% yacc parse.y parse.y contains 4 shift/reduce conflicts and 13 reduce/reduce conflicts.

As expected, conflicts are aplenty. If you are interested, you add the option `-v` to `yacc` and build a log. The nature of the conflicts should be shown there in great detail.

Implementation

So, what is there to do? In Ruby, on the symbol level (that is, on the scanner level) the normal `if` is distinguished from the postfix `if` by them being `kIF` and `kIF_MOD` respectively. This also applies to all other postfix operators. In all, there are five – `kUNLESS_MOD kUNTIL_MOD kWHILE_MOD` `kRESCUE_MOD` and `kIF_MOD` The distinction is made here:

▼ `yylex`-Reserved word

4173 struct kwtable kw;

4174

4175 / See if it is a reserved word. /

4176 kw = rb_reserved_word(tok(), toklen());

4177 if (kw) {

4178 enum lex_state state = lex_state;

4179 lex_state = kw→state;

4180 if (state == EXPR_FNAME) {

4181 yylval.id = rb_intern(kw→name);

4182 }

4183 if (kw→id0 == kDO) {

4184 if (COND_P()) return kDO_COND;

4185 if (CMDARG_P() && state != EXPR_CMDARG)

4186 return kDO_BLOCK;

4187 if (state == EXPR_ENDARG)

4188 return kDO_BLOCK;

4189 return kDO;

4190 }

4191 if (state == EXPR_BEG) /* Here **/

4192 return kw→id0;

4193 else {

4194 if (kw→id0 != kw→id1)

4195 lex_state = EXPR_BEG;

4196 return kw→id1;

4197 }

4198 }

(parse.y)

This is located at the end of `yylex` after the identifiers are scanned. The part that handles modifiers is the last (innermost) `if`〜`else` Whether the return value is altered can be determined by whether or not the state is `EXPR_BEG`. This is where a modifier is identified. Basically, the variable `kw` is the key and if you look far above you will find that it is `struct kwtable`

I’ve already described in the previous chapter how `struct kwtable` is a structure defined in `keywords` and the hash function `rb_reserved_word()` is created by `gperf`. I’ll show the structure here again.

▼ `keywords` – `struct kwtable`

1 struct kwtable {char *name; int id2; enum lex_state state;};

(keywords)

I’ve already explained about `name` and `id0` – they are the reserved word name and its symbol. Here I will speak about the remaining members.

First, `id1` is a symbol to deal with modifiers. For example, in case of `if` that would be `kIF_MOD`. When a reserved word does not have a modifier equivalent, `id0` and `id1` contain the same things.

Because `state` is `enum lex_state` it is the state to which a transition should occur after the reserved word is read. Below is a list created in the `kwstat.rb` tool which I made. The tool can be found on the CD.

% kwstat.rb ruby/keywords ---- EXPR_ARG defined? super yield ---- EXPR_BEG and case else ensure if module or unless when begin do elsif for in not then until while ---- EXPR_CLASS class ---- EXPR_END BEGIN __FILE__ end nil retry true END __LINE__ false redo self ---- EXPR_FNAME alias def undef ---- EXPR_MID break next rescue return ---- modifiers if rescue unless until while

The `do` conflict

The problem

There are two iterator forms – `do`〜`end` and `{`〜`}` Their difference is in priority – `{`〜`}` has a much higher priority. A higher priority means that as part of the grammar a unit is “small” which means it can be put into a smaller rule. For example, it can be put not into `stmt` but `expr` or `primary`. In the past `{`〜`}` iterators were in `primary` while `do`〜`end` iterators were in `stmt`

By the way, there has been a request for an expression like this:

m do .... end + m do .... end

To allow for this, put the `do`〜`end` iterator in `arg` or `primary`. Incidentally, the condition for `while` is `expr`, meaning it contains `arg` and `primary`, so the `do` will cause a conflict here. Basically, it looks like this:

while m do .... end

At first glance, the `do` looks like the `do` of `while`. However, a closer look reveals that it could be a `m do`〜`end` bundling. Something that’s not obvious even to a person will definitely cause `yacc` to conflict. Let’s try it in practice.

/* do conflict experiment */ %token kWHILE kDO tIDENTIFIER kEND %% expr: kWHILE expr kDO expr kEND | tIDENTIFIER | tIDENTIFIER kDO expr kEND

I simplified the example to only include `while`, variable referencing and iterators. This rule causes a shift/reduce conflict if the head of the conditional contains `tIDENTIFIER`. If `tIDENTIFIER` is used for variable referencing and `do` is appended to `while`, then it’s reduction. If it’s made an iterator `do`, then it’s a shift.

Unfortunately, in a shift/reduce conflict the shift is prioritized, so if left unchecked, `do` will become an iterator `do`. That said, even if a reduction is forced through operator priorities or some other method, `do` won’t shift at all, becoming unusable. Thus, to solve the problem without any contradictions, we need to either deal with on the scanner level or write a rule that allows to use operators without putting the `do`〜`end` iterator into `expr`.

However, not putting `do`〜`end` into `expr` is not a realistic goal. That would require all rules for `expr` (as well as for `arg` and `primary`) to be repeated. This leaves us only the scanner solution.

Rule-level solution

Below is a simplified example of a relevant rule.

▼ `do` symbol

primary : kWHILE expr_value do compstmt kENDdo : term | kDO_COND

primary : operation brace_block | method_call brace_block

brace_block : ‘{’ opt_block_var compstmt ‘}’ | kDO opt_block_var compstmt kEND

As you can see, the terminal symbols for the `do` of `while` and for the iterator `do` are different. For the former it’s `kDO_COND` while for the latter it’s `kDO` Then it’s simply a matter of pointing that distinction out to the scanner.

Symbol-level solution

Below is a partial view of the `yylex` section that processes reserved words. It’s the only part tasked with processing `do` so looking at this code should be enough to understand the criteria for making the distinction.

▼ `yylex`-Identifier-Reserved word

4183 if (kw→id0 == kDO) { 4184 if (COND_P()) return kDO_COND; 4185 if (CMDARG_P() && state != EXPR_CMDARG) 4186 return kDO_BLOCK; 4187 if (state == EXPR_ENDARG) 4188 return kDO_BLOCK; 4189 return kDO; 4190 }(parse.y)

It’s a little messy, but you only need the part associated with `kDO_COND`. That is because only two comparisons are meaningful. The first is the comparison between `kDO_COND` and `kDO`/`kDO_BLOCK` The second is the comparison between `kDO` and `kDO_BLOCK`. The rest are meaningless. Right now we only need to distinguish the conditional `do` – leave all the other conditions alone.

Basically, `COND_P()` is the key.

`COND_P()`

`cond_stack`

`COND_P()` is defined close to the head of `parse.y`

▼ `cond_stack`

75 #ifdef HAVE_LONG_LONG

76 typedef unsigned LONG_LONG stack_type;

77 #else

78 typedef unsigned long stack_type;

79 #endif

80

81 static stack_type cond_stack = 0;

82 #define COND_PUSH(n) (cond_stack = (cond_stack<<1)|((n)&1))

83 #define COND_POP() (cond_stack >>= 1)

84 #define COND_LEXPOP() do {\

85 int last = COND_P();\

86 cond_stack >>= 1;\

87 if (last) cond_stack |= 1;\

88 } while (0)

89 #define COND_P() (cond_stack&1)

(parse.y)

The type `stack_type` is either `long` (over 32 bit) or `long long` (over 64 bit). `cond_stack` is initialized by `yycompile()` at the start of parsing and after that is handled only through macros. All you need, then, is to understand those macros.

If you look at `COND_PUSH`/`POP` you will see that these macros use integers as stacks consisting of bits.

MSB← →LSB ...0000000000 Initial value 0 ...0000000001 COND_PUSH(1) ...0000000010 COND_PUSH(0) ...0000000101 COND_PUSH(1) ...0000000010 COND_POP() ...0000000100 COND_PUSH(0) ...0000000010 COND_POP()

As for `COND_P()`, since it determines whether or not the least significant bit (LSB) is a 1, it effectively determines whether the head of the stack is a 1.

The remaining `COND_LEXPOP()` is a little weird. It leaves `COND_P()` at the head of the stack and executes a right shift. Basically, it “crushes” the second bit from the bottom with the lowermost bit.

MSB← →LSB ...0000000000 Initial value 0 ...0000000001 COND_PUSH(1) ...0000000010 COND_PUSH(0) ...0000000101 COND_PUSH(1) ...0000000011 COND_LEXPOP() ...0000000100 COND_PUSH(0) ...0000000010 COND_LEXPOP()

((errata:

It leaves `COND_P()` only when it is 1.

When `COND_P()` is 0 and the second bottom bit is 1,

it would become 1 after doing LEXPOP,

thus `COND_P()` is not left in this case.

))

Now I will explain what that means.

Investigating the function

Let us investigate the function of this stack. To do that I will list up all the parts where `COND_PUSH() COND_POP()` are used.

| kWHILE {COND_PUSH(1);} expr_value do {COND_POP();}

--

| kUNTIL {COND_PUSH(1);} expr_value do {COND_POP();}

--

| kFOR block_var kIN {COND_PUSH(1);} expr_value do {COND_POP();}

--

case '(':

:

:

COND_PUSH(0);

CMDARG_PUSH(0);

--

case '[':

:

:

COND_PUSH(0);

CMDARG_PUSH(0);

--

case '{':

:

:

COND_PUSH(0);

CMDARG_PUSH(0);

--

case ']':

case '}':

case ')':

COND_LEXPOP();

CMDARG_LEXPOP();

From this we can derive the following general rules

- At the start of a conditional expression `PUSH`

- At opening parenthesis `PUSH`

- At the end of a conditional expression `POP()`

- At closing parenthesis`LEXPOP()`

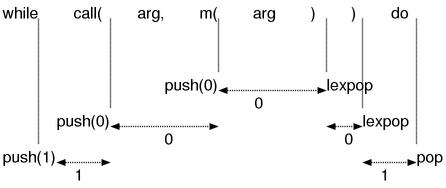

With this, you should see how to use it. If you think about it for a minute, the name `cond_stack` itself is clearly the name for a macro that determines whether or not it’s on the same level as the conditional expression (see image 2)

Using this trick should also make situations like the one shown below easy to deal with.

while (m do .... end) # do is an iterator do(kDO) .... end

This means that on a 32-bit machine in the absence of `long long` if conditional expressions or parentheses are nested at 32 levels, things could get strange. Of course, in reality you won’t need to nest so deep so there’s no actual risk.

Finally, the definition of `COND_LEXPOP()` looks a bit strange – that seems to be a way of dealing with lookahead. However, the rules now do not allow for lookahead to occur, so there’s no purpose to make the distinction between `POP` and `LEXPOP`. Basically, at this time it would be correct to say that `COND_LEXPOP()` has no meaning.

`tLPAREN_ARG`(1)

The problem

This one is very complicated. It only became workable in Ruby 1.7 and only fairly recently. The core of the issue is interpreting this:

call (expr) + 1

As one of the following

(call(expr)) + 1 call((expr) + 1)

In the past, it was always interpreted as the former. That is, the parentheses were always treated as “Method parameter parentheses”. But since Ruby 1.7 it became possible to interpret it as the latter – basically, if a space is added, the parentheses become “Parentheses of `expr`”

I will also provide an example to explain why the interpretation changed. First, I wrote a statement as follows

p m() + 1

So far so good. But let’s assume the value returned by `m` is a fraction and there are too many digits. Then we will have it displayed as an integer.

p m() + 1 .to_i # ??

Uh-oh, we need parentheses.

p (m() + 1).to_i

How to interpret this? Up to 1.6 it will be this

(p(m() + 1)).to_i

The much-needed `to_i` is rendered meaningless, which is unacceptable. To counter that, adding a space between it and the parentheses will cause the parentheses to be treated specially as `expr` parentheses.

For those eager to test this, this feature was implemented in `parse.y` revision 1.100(2001-05-31). Thus, it should be relatively prominent when looking at the differences between it and 1.99. This is the command to find the difference.

~/src/ruby % cvs diff -r1.99 -r1.100 parse.y

Investigation

First let us look at how the set-up works in reality. Using the `ruby-lexer` tool{`ruby-lexer`: located in `tools/ruby-lexer.tar.gz` on the CD} we can look at the list of symbols corresponding to the program.

% ruby-lexer -e 'm(a)'

tIDENTIFIER '(' tIDENTIFIER ')' '\n'

Similarly to Ruby, `-e` is the option to pass the program directly from the command line. With this we can try all kinds of things. Let’s start with the problem at hand – the case where the first parameter is enclosed in parentheses.

% ruby-lexer -e 'm (a)' tIDENTIFIER tLPAREN_ARG tIDENTIFIER ')' '\n'

After adding a space, the symbol of the opening parenthesis became `tLPAREN_ARG`. Now let’s look at normal expression parentheses.

% ruby-lexer -e '(a)' tLPAREN tIDENTIFIER ')' '\n'

For normal expression parentheses it seems to be `tLPAREN`. To sum up:

| Input | Symbol of opening parenthesis |

|---|---|

| `m(a)` | `‘(’` |

| `m (a)` | `tLPAREN_ARG` |

| `(a)` | `tLPAREN` |

Thus the focus is distinguishing between the three. For now `tLPAREN_ARG` is the most important.

The case of one parameter

We’ll start by looking at the `yylex()` section for `‘(’`

▼ `yylex`-`‘(’`

3841 case ‘(’:

3842 command_start = Qtrue;

3843 if (lex_state == EXPR_BEG || lex_state == EXPR_MID) {

3844 c = tLPAREN;

3845 }

3846 else if (space_seen) {

3847 if (lex_state == EXPR_CMDARG) {

3848 c = tLPAREN_ARG;

3849 }

3850 else if (lex_state == EXPR_ARG) {

3851 c = tLPAREN_ARG;

3852 yylval.id = last_id;

3853 }

3854 }

3855 COND_PUSH(0);

3856 CMDARG_PUSH(0);

3857 lex_state = EXPR_BEG;

3858 return c;

(parse.y)

Since the first `if` is `tLPAREN` we’re looking at a normal expression parenthesis. The distinguishing feature is that `lex_state` is either `BEG` or `MID` – that is, it’s clearly at the beginning of the expression.

The following `space_seen` shows whether the parenthesis is preceded by a space. If there is a space and `lex_state` is either `ARG` or `CMDARG`, basically if it’s before the first parameter, the symbol is not `‘(’` but `tLPAREN_ARG`. This way, for example, the following situation can be avoided

m( # Parenthesis not preceded by a space. Method parenthesis ('(')

m arg, ( # Unless first parameter, expression parenthesis (tLPAREN)

When it is neither `tLPAREN` nor `tLPAREN_ARG`, the input character `c` is used as is and becomes `‘(’`. This will definitely be a method call parenthesis.

If such a clear distinction is made on the symbol level, no conflict should occur even if rules are written as usual. Simplified, it becomes something like this:

stmt : command_call

method_call : tIDENTIFIER '(' args ')' /* Normal method */

command_call : tIDENTIFIER command_args /* Method with parentheses omitted */

command_args : args

args : arg

: args ',' arg

arg : primary

primary : tLPAREN compstmt ')' /* Normal expression parenthesis */

| tLPAREN_ARG expr ')' /* First parameter enclosed in parentheses */

| method_call

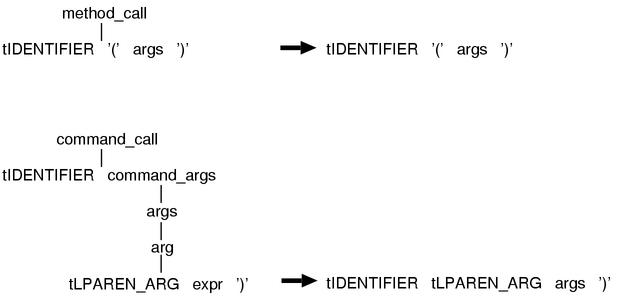

Now I need you to focus on `method_call` and `command_call` If you leave the `‘(’` without introducing `tLPAREN_ARG`, then `command_args` will produce `args`, `args` will produce `arg`, `arg` will produce `primary`. Then, `‘(’` will appear from `tLPAREN_ARG` and conflict with `method_call` (see image 3)

The case of two parameters and more

One might think that if the parenthesis becomes `tLPAREN_ARG` all will be well. That is not so. For example, consider the following

m (a, a, a)

Before now, expressions like this one were treated as method calls and did not produce errors. However, if `tLPAREN_ARG` is introduced, the opening parenthesis becomes an `expr` parenthesis, and if two or more parameters are present, that will cause a parse error. This needs to be resolved for the sake of compatibility.

Unfortunately, rushing ahead and just adding a rule like

command_args : tLPAREN_ARG args ')'

will just cause a conflict. Let’s look at the bigger picture and think carefully.

stmt : command_call

| expr

expr : arg

command_call : tIDENTIFIER command_args

command_args : args

| tLPAREN_ARG args ')'

args : arg

: args ',' arg

arg : primary

primary : tLPAREN compstmt ')'

| tLPAREN_ARG expr ')'

| method_call

method_call : tIDENTIFIER '(' args ')'

Look at the first rule of `command_args` Here, `args` produces `arg` Then `arg` produces `primary` and out of there comes the `tLPAREN_ARG` rule. And since `expr` contains `arg` and as it is expanded, it becomes like this:

command_args : tLPAREN_ARG arg ')' | tLPAREN_ARG arg ')'

This is a reduce/reduce conflict, which is very bad.

So, how can we deal with only 2+ parameters without causing a conflict? We’ll have to write to accommodate for that situation specifically. In practice, it’s solved like this:

▼ `command_args`

command_args : open_argsopen_args : call_args | tLPAREN_ARG ‘)’ | tLPAREN_ARG call_args2 ‘)’

call_args : command | args opt_block_arg | args ‘,’ tSTAR arg_value opt_block_arg | assocs opt_block_arg | assocs ‘,’ tSTAR arg_value opt_block_arg | args ‘,’ assocs opt_block_arg | args ‘,’ assocs ‘,’ tSTAR arg opt_block_arg | tSTAR arg_value opt_block_arg | block_arg

call_args2 : arg_value ‘,’ args opt_block_arg | arg_value ‘,’ block_arg | arg_value ‘,’ tSTAR arg_value opt_block_arg | arg_value ‘,’ args ‘,’ tSTAR arg_value opt_block_arg | assocs opt_block_arg | assocs ‘,’ tSTAR arg_value opt_block_arg | arg_value ‘,’ assocs opt_block_arg | arg_value ‘,’ args ‘,’ assocs opt_block_arg | arg_value ‘,’ assocs ‘,’ tSTAR arg_value opt_block_arg | arg_value ‘,’ args ‘,’ assocs ‘,’ tSTAR arg_value opt_block_arg | tSTAR arg_value opt_block_arg | block_arg

primary : literal | strings | xstring : | tLPAREN_ARG expr ‘)’

Here `command_args` is followed by another level – `open_args` which may not be reflected in the rules without consequence. The key is the second and third rules of this `open_args` This form is similar to the recent example, but is actually subtly different. The difference is that `call_args2` has been introduced. The defining characteristic of this `call_args2` is that the number of parameters is always two or more. This is evidenced by the fact that most rules contain `‘,’` The only exception is `assocs`, but since `assocs` does not come out of `expr` it cannot conflict anyway.

That wasn’t a very good explanation. To put it simply, in a grammar where this:

command_args : call_args

doesn’t work, and only in such a grammar, the next rule is used to make an addition. Thus, the best way to think here is “In what kind of grammar would this rule not work?” Furthermore, since a conflict only occurs when the `primary` of `tLPAREN_ARG` appears at the head of `call_args`, the scope can be limited further and the best way to think is “In what kind of grammar does this rule not work when a `tIDENTIFIER tLPAREN_ARG` line appears?” Below are a few examples.

m (a, a)

This is a situation when the `tLPAREN_ARG` list contains two or more items.

m ()

Conversely, this is a situation when the `tLPAREN_ARG` list is empty.

m (*args) m (&block) m (k => v)

This is a situation when the `tLPAREN_ARG` list contains a special expression (one not present in `expr`).

This should be sufficient for most cases. Now let’s compare the above with a practical implementation.

▼ `open_args`(1)

open_args : call_args | tLPAREN_ARG ‘)’

First, the rule deals with empty lists

▼ `open_args`(2)

| tLPAREN_ARG call_args2 ‘)’call_args2 : arg_value ‘,’ args opt_block_arg | arg_value ‘,’ block_arg | arg_value ‘,’ tSTAR arg_value opt_block_arg | arg_value ‘,’ args ‘,’ tSTAR arg_value opt_block_arg | assocs opt_block_arg | assocs ‘,’ tSTAR arg_value opt_block_arg | arg_value ‘,’ assocs opt_block_arg | arg_value ‘,’ args ‘,’ assocs opt_block_arg | arg_value ‘,’ assocs ‘,’ tSTAR arg_value opt_block_arg | arg_value ‘,’ args ‘,’ assocs ‘,’ tSTAR arg_value opt_block_arg | tSTAR arg_value opt_block_arg | block_arg

And `call_args2` deals with elements containing special types such as `assocs`, passing of arrays or passing of blocks. With this, the scope is now sufficiently broad.

`tLPAREN_ARG`(2)

The problem

In the previous section I said that the examples provided should be sufficient for “most” special method call expressions. I said “most” because iterators are still not covered. For example, the below statement will not work:

m (a) {....}

m (a) do .... end

In this section we will once again look at the previously introduced parts with solving this problem in mind.

Rule-level solution

Let us start with the rules. The first part here is all familiar rules, so focus on the `do_block` part

▼ `command_call`

command_call : command | block_commandcommand : operation command_args

command_args : open_args

open_args : call_args | tLPAREN_ARG ‘)’ | tLPAREN_ARG call_args2 ‘)’

block_command : block_call

block_call : command do_block

do_block : kDO_BLOCK opt_block_var compstmt ‘}’ | tLBRACE_ARG opt_block_var compstmt ‘}’

Both `do` and `{` are completely new symbols `kDO_BLOCK` and `tLBRACE_ARG`. Why isn’t it `kDO` or `‘{’` you ask? In this kind of situation the best answer is an experiment, so we will try replacing `kDO_BLOCK` with `kDO` and `tLBRACE_ARG` with `‘{’` and processing that with `yacc`

% yacc parse.y conflicts: 2 shift/reduce, 6 reduce/reduce

It conflicts badly. A further investigation reveals that this statement is the cause.

m (a), b {....}

That is because this kind of statement is already supposed to work. `b{….}` becomes `primary`. And now a rule has been added that concatenates the block with `m` That results in two possible interpretations:

m((a), b) {....}

m((a), (b {....}))

This is the cause of the conflict – namely, a 2 shift/reduce conflict.

The other conflict has to do with `do`〜`end`

m((a)) do .... end # Add do〜end using block_call m((a)) do .... end # Add do〜end using primary

These two conflict. This is 6 reduce/reduce conflict.

`{`〜`}` iterator

This is the important part. As shown previously, you can avoid a conflict by changing the `do` and `‘{’` symbols.

▼ `yylex`-`‘{’`

3884 case ‘{’:

3885 if (IS_ARG() || lex_state == EXPR_END)

3886 c = ‘{’; /* block (primary) /

3887 else if (lex_state == EXPR_ENDARG)

3888 c = tLBRACE_ARG; / block (expr) /

3889 else

3890 c = tLBRACE; / hash */

3891 COND_PUSH(0);

3892 CMDARG_PUSH(0);

3893 lex_state = EXPR_BEG;

3894 return c;

(parse.y)

`IS_ARG()` is defined as

▼ `IS_ARG`

3104 #define IS_ARG() (lex_state == EXPR_ARG || lex_state == EXPR_CMDARG)(parse.y)

Thus, when the state is `EXPR_ENDARG` it will always be false. In other words, when `lex_state` is `EXPR_ENDARG`, it will always become `tLBRACE_ARG`, so the key to everything is the transition to `EXPR_ENDARG`.

`EXPR_ENDARG`

Now we need to know how to set `EXPR_ENDARG` I used `grep` to find where it is assigned.

▼ Transition to`EXPR_ENDARG`

open_args : call_args

| tLPAREN_ARG {lex_state = EXPR_ENDARG;} ‘)’

| tLPAREN_ARG call_args2 {lex_state = EXPR_ENDARG;} ‘)’

primary : tLPAREN_ARG expr {lex_state = EXPR_ENDARG;} ‘)’

That’s strange. One would expect the transition to `EXPR_ENDARG` to occur after the closing parenthesis corresponding to `tLPAREN_ARG`, but it’s actually assigned before `‘)’` I ran `grep` a few more times thinking there might be other parts setting the `EXPR_ENDARG` but found nothing.

Maybe there’s some mistake. Maybe `lex_state` is being changed some other way. Let’s use `rubylex-analyser` to visualize the `lex_state` transition.

% rubylex-analyser -e 'm (a) { nil }'

+EXPR_BEG

EXPR_BEG C "m" tIDENTIFIER EXPR_CMDARG

EXPR_CMDARG S "(" tLPAREN_ARG EXPR_BEG

0:cond push

0:cmd push

1:cmd push-

EXPR_BEG C "a" tIDENTIFIER EXPR_CMDARG

EXPR_CMDARG ")" ')' EXPR_END

0:cond lexpop

1:cmd lexpop

+EXPR_ENDARG

EXPR_ENDARG S "{" tLBRACE_ARG EXPR_BEG

0:cond push

10:cmd push

0:cmd resume

EXPR_BEG S "nil" kNIL EXPR_END

EXPR_END S "}" '}' EXPR_END

0:cond lexpop

0:cmd lexpop

EXPR_END "\n" \n EXPR_BEG

The three big branching lines show the state transition caused by `yylex()`. On the left is the state before `yylex()` The middle two are the word text and its symbols. Finally, on the right is the `lex_state` after `yylex()`

The problem here are parts of single lines that come out as `+EXPR_ENDARG`. This indicates a transition occurring during parser action. According to this, for some reason an action is executed after reading the `‘)’` a transition to `EXPR_ENDARG` occurs and `‘{’` is nicely changed into `tLBRACE_ARG` This is actually a pretty high-level technique – generously (ab)using the LALR up to the (1).

Abusing the lookahead

`ruby -y` can bring up a detailed display of the `yacc` parser engine. This time we will use it to more closely trace the parser.

% ruby -yce 'm (a) {nil}' 2>&1 | egrep '^Reading|Reducing'

Reducing via rule 1 (line 303), -> @1

Reading a token: Next token is 304 (tIDENTIFIER)

Reading a token: Next token is 340 (tLPAREN_ARG)

Reducing via rule 446 (line 2234), tIDENTIFIER -> operation

Reducing via rule 233 (line 1222), -> @6

Reading a token: Next token is 304 (tIDENTIFIER)

Reading a token: Next token is 41 (')')

Reducing via rule 392 (line 1993), tIDENTIFIER -> variable

Reducing via rule 403 (line 2006), variable -> var_ref

Reducing via rule 256 (line 1305), var_ref -> primary

Reducing via rule 198 (line 1062), primary -> arg

Reducing via rule 42 (line 593), arg -> expr

Reducing via rule 260 (line 1317), -> @9

Reducing via rule 261 (line 1317), tLPAREN_ARG expr @9 ')' -> primary

Reading a token: Next token is 344 (tLBRACE_ARG)

:

:

Here we’re using the option `-c` which stops the process at just compiling and `-e` which allows to give a program from the command line. And we’re using `grep` to single out token read and reduction reports.

Start by looking at the middle of the list. `‘)’` is read. Now look at the end – the reduction (execution) of embedding action (`@9`) finally happens. Indeed, this would allow `EXPR_ENDARG ` to be set after the `‘)’` before the `‘{’` But is this always the case? Let’s take another look at the part where it’s set.

Rule 1 tLPAREN_ARG {lex_state = EXPR_ENDARG;} ')'

Rule 2 tLPAREN_ARG call_args2 {lex_state = EXPR_ENDARG;} ')'

Rule 3 tLPAREN_ARG expr {lex_state = EXPR_ENDARG;} ')'

The embedding action can be substituted with an empty rule. For example, we can rewrite this using rule 1 with no change in meaning whatsoever.

target : tLPAREN_ARG tmp ')'

tmp :

{

lex_state = EXPR_ENDARG;

}

Assuming that this is before `tmp`, it’s possible that one terminal symbol will be read by lookahead. Thus we can skip the (empty) `tmp` and read the next. And if we are certain that lookahead will occur, the assignment to `lex_state` is guaranteed to change to `EXPR_ENDARG` after `‘)’` But is `‘)’` certain to be read by lookahead in this rule?

Ascertaining lookahead

This is actually pretty clear. Think about the following input.

m () { nil } # A

m (a) { nil } # B

m (a,b,c) { nil } # C

I also took the opportunity to rewrite the rule to make it easier to understand (with no actual changes).

rule1: tLPAREN_ARG e1 ')' rule2: tLPAREN_ARG one_arg e2 ')' rule3: tLPAREN_ARG more_args e3 ')' e1: /* empty */ e2: /* empty */ e3: /* empty */

First, the case of input A. Reading up to

m ( # ... tLPAREN_ARG

we arrive before the `e1`. If `e1` is reduced here, another rule cannot be chosen anymore. Thus, a lookahead occurs to confirm whether to reduce `e1` and continue with `rule1` to the bitter end or to choose a different rule. Accordingly, if the input matches `rule1` it is certain that `‘)’` will be read by lookahead.

On to input B. First, reading up to here

m ( # ... tLPAREN_ARG

Here a lookahead occurs for the same reason as described above. Further reading up to here

m (a # ... tLPAREN_ARG '(' tIDENTIFIER

Another lookahead occurs. It occurs because depending on whether what follows is a `‘,’` or a `‘)’` a decision is made between `rule2` and `rule3` If what follows is a `‘,’` then it can only be a comma to separate parameters, thus `rule3` the rule for two or more parameters, is chosen. This is also true if the input is not a simple `a` but something like an `if` or literal. When the input is complete, a lookahead occurs to choose between `rule2` and `rule3` - the rules for one parameter and two or more parameters respectively.

The presence of a separate embedding action is present before `‘)’` in every rule. There’s no going back after an action is executed, so the parser will try to postpone executing an action until it is as certain as possible. For that reason, situations when this certainty cannot be gained with a single lookahead should be excluded when building a parser as it is a conflict.

Proceeding to input C.

m (a, b, c

At this point anything other than `rule3` is unlikely so we’re not expecting a lookahead. And yet, that is wrong. If the following is `‘(’` then it’s a method call, but if the following is `‘,’` or `‘)’` it needs to be a variable reference. Basically, this time a lookahead is needed to confirm parameter elements instead of embedding action reduction.

But what about the other inputs? For example, what if the third parameter is a method call?

m (a, b, c(....) # ... ',' method_call

Once again a lookahead is necessary because a choice needs to be made between shift and reduction depending on whether what follows is `‘,’` or `‘)’`. Thus, in this rule in all instances the `‘)’` is read before the embedding action is executed. This is quite complicated and more than a little impressive.

But would it be possible to set `lex_state` using a normal action instead of an embedding action? For example, like this:

| tLPAREN_ARG ')' { lex_state = EXPR_ENDARG; }

This won’t do because another lookahead is likely to occur before the action is reduced. This time the lookahead works to our disadvantage. With this it should be clear that abusing the lookahead of a LALR parser is pretty tricky and not something a novice should be doing.

`do`〜`end` iterator

So far we’ve dealt with the `{`〜`}` iterator, but we still have `do`〜`end` left. Since they’re both iterators, one would expect the same solutions to work, but it isn’t so. The priorities are different. For example,

m a, b {....} # m(a, (b{....}))

m a, b do .... end # m(a, b) do....end

Thus it’s only appropriate to deal with them differently.

That said, in some situations the same solutions do apply. The example below is one such situation

m (a) {....}

m (a) do .... end

In the end, our only option is to look at the real thing. Since we’re dealing with `do` here, we should look in the part of `yylex()` that handles reserved words.

▼ `yylex`-Identifiers-Reserved words-`do`

4183 if (kw→id0 == kDO) { 4184 if (COND_P()) return kDO_COND; 4185 if (CMDARG_P() && state != EXPR_CMDARG) 4186 return kDO_BLOCK; 4187 if (state == EXPR_ENDARG) 4188 return kDO_BLOCK; 4189 return kDO; 4190 }(parse.y)

This time we only need the part that distinguishes between `kDO_BLOCK` and `kDO`. Ignore `kDO_COND` Only look at what’s always relevant in a finite-state scanner.

The decision-making part using `EXPR_ENDARG` is the same as `tLBRACE_ARG` so priorities shouldn’t be an issue here. Similarly to `‘{’` the right course of action is probably to make it `kDO_BLOCK`

((errata:

In the following case, priorities should have an influence.

(But it does not in the actual code. It means this is a bug.)

m m (a) { ... } # This should be interpreted as m(m(a) {...}),

# but is interpreted as m(m(a)) {...}

m m (a) do ... end # as the same as this: m(m(a)) do ... end

))

The problem lies with `CMDARG_P()` and `EXPR_CMDARG`. Let’s look at both.

`CMDARG_P()`

▼ `cmdarg_stack`

91 static stack_type cmdarg_stack = 0;

92 #define CMDARG_PUSH(n) (cmdarg_stack = (cmdarg_stack<<1)|((n)&1))

93 #define CMDARG_POP() (cmdarg_stack >>= 1)

94 #define CMDARG_LEXPOP() do {\

95 int last = CMDARG_P();\

96 cmdarg_stack >>= 1;\

97 if (last) cmdarg_stack |= 1;\

98 } while (0)

99 #define CMDARG_P() (cmdarg_stack&1)

(parse.y)

The structure and interface (macro) of `cmdarg_stack` is completely identical to `cond_stack`. It’s a stack of bits. Since it’s the same, we can use the same means to investigate it. Let’s list up the places which use it. First, during the action we have this:

command_args : {

$<num>$ = cmdarg_stack;

CMDARG_PUSH(1);

}

open_args

{

/* CMDARG_POP() */

cmdarg_stack = $<num>1;

$$ = $2;

}

`$

But why use a hide-restore system instead of a simple push-pop? That will be explained at the end of this section.

Searching `yylex()` for more `CMDARG` relations, I found this.

| Token | Relation |

|---|---|

| `‘(’ ‘[’ ‘{’` | `CMDARG_PUSH(0)` |

| `‘)’ ‘]’ ‘}’` | `CMDARG_LEXPOP()` |

Basically, as long as it is enclosed in parentheses, `CMDARG_P()` is false.

Consider both, and it can be said that when `command_args` , a parameter for a method call with parentheses omitted, is not enclosed in parentheses `CMDARG_P()` is true.

`EXPR_CMDARG`

Now let’s take a look at one more condition – `EXPR_CMDARG` Like before, let us look for place where a transition to `EXPR_CMDARG` occurs.

▼ `yylex`-Identifiers-State Transitions

4201 if (lex_state == EXPR_BEG ||

4202 lex_state == EXPR_MID ||

4203 lex_state == EXPR_DOT ||

4204 lex_state == EXPR_ARG ||

4205 lex_state == EXPR_CMDARG) {

4206 if (cmd_state)

4207 lex_state = EXPR_CMDARG;

4208 else

4209 lex_state = EXPR_ARG;

4210 }

4211 else {

4212 lex_state = EXPR_END;

4213 }

(parse.y)

This is code that handles identifiers inside `yylex()` Leaving aside that there are a bunch of `lex_state` tests in here, let’s look first at `cmd_state` And what is this?

▼ `cmd_state`

3106 static int

3107 yylex()

3108 {

3109 static ID last_id = 0;

3110 register int c;

3111 int space_seen = 0;

3112 int cmd_state;

3113

3114 if (lex_strterm) {

/* ……omitted…… */

3132 }

3133 cmd_state = command_start;

3134 command_start = Qfalse;

(parse.y)

Turns out it’s an `yylex` local variable. Furthermore, an investigation using `grep` revealed that here is the only place where its value is altered. This means it’s just a temporary variable for storing `command_start` during a single run of `yylex`

When does `command_start` become true, then?

▼ `command_start`

2327 static int command_start = Qtrue;2334 static NODE* 2335 yycompile(f, line) 2336 char *f; 2337 int line; 2338 { : 2380 command_start = 1;

static int yylex() { : case ‘\n’: /* ……omitted…… */ 3165 command_start = Qtrue; 3166 lex_state = EXPR_BEG; 3167 return ‘\n’;

3821 case ‘;’: 3822 command_start = Qtrue;

3841 case ‘(’: 3842 command_start = Qtrue;

(parse.y)

From this we understand that `command_start` becomes true when one of the `parse.y` static variables `\n ; (` is scanned.

Summing up what we’ve covered up to now, first, when `\n ; (` is read, `command_start` becomes true and during the next `yylex()` run `cmd_state` becomes true.

And here is the code in `yylex()` that uses `cmd_state`

▼ `yylex`-Identifiers-State transitions

4201 if (lex_state == EXPR_BEG ||

4202 lex_state == EXPR_MID ||

4203 lex_state == EXPR_DOT ||

4204 lex_state == EXPR_ARG ||

4205 lex_state == EXPR_CMDARG) {

4206 if (cmd_state)

4207 lex_state = EXPR_CMDARG;

4208 else

4209 lex_state = EXPR_ARG;

4210 }

4211 else {

4212 lex_state = EXPR_END;

4213 }

(parse.y)

From this we understand the following: when after `\n ; (` the state is `EXPR_BEG MID DOT ARG CMDARG` and an identifier is read, a transition to `EXPR_CMDARG` occurs. However, `lex_state` can only become `EXPR_BEG` following a `\n ; (` so when a transition occurs to `EXPR_CMDARG` the `lex_state` loses its meaning. The `lex_state` restriction is only important to transitions dealing with `EXPR_ARG`

Based on the above we can now think of a situation where the state is `EXPR_CMDARG`. For example, see the one below. The underscore is the current position.

m _ m(m _ m m _

((errata:

The third one “m m _” is not `EXPR_CMDARG`. (It is `EXPR_ARG`.)

))

Conclusion

Let us now return to the `do` decision code.

▼ `yylex`-Identifiers-Reserved words-`kDO`-`kDO_BLOCK`

4185 if (CMDARG_P() && state != EXPR_CMDARG) 4186 return kDO_BLOCK;(parse.y)

Inside the parameter of a method call with parentheses omitted but not before the first parameter. That means from the second parameter of `command_call` onward. Basically, like this:

m arg, arg do .... end m (arg), arg do .... end

Why is the case of `EXPR_CMDARG` excluded? This example should clear It up

m do .... end

This pattern can already be handled using the `do`〜`end` iterator which uses `kDO` and is defined in `primary` Thus, including that case would cause another conflict.

Reality and truth

Did you think we’re done? Not yet. Certainly, the theory is now complete, but only if everything that has been written is correct. As a matter of fact, there is one falsehood in this section. Well, more accurately, it isn’t a falsehood but an inexact statement. It’s in the part about `CMDARG_P()`

Actually, `CMDARG_P()` becomes true when inside `command_args` , that is to say, inside the parameter of a method call with parentheses omitted.

But where exactly is “inside the parameter of a method call with parentheses omitted”? Once again, let us use `rubylex-analyser` to inspect in detail.

% rubylex-analyser -e 'm a,a,a,a;' +EXPR_BEG EXPR_BEG C "m" tIDENTIFIER EXPR_CMDARG EXPR_CMDARG S "a" tIDENTIFIER EXPR_ARG 1:cmd push- EXPR_ARG "," ',' EXPR_BEG EXPR_BEG "a" tIDENTIFIER EXPR_ARG EXPR_ARG "," ',' EXPR_BEG EXPR_BEG "a" tIDENTIFIER EXPR_ARG EXPR_ARG "," ',' EXPR_BEG EXPR_BEG "a" tIDENTIFIER EXPR_ARG EXPR_ARG ";" ';' EXPR_BEG 0:cmd resume EXPR_BEG C "\n" ' EXPR_BEG

The `1:cmd push-` in the right column is the push to `cmd_stack`. When the rightmost digit in that line is 1 `CMDARG_P()` become true. To sum up, the period of `CMDARG_P()` can be described as:

From immediately after the first parameter of a method call with parentheses omitted To the terminal symbol following the final parameter

But, very strictly speaking, even this is still not entirely accurate.

% rubylex-analyser -e 'm a(),a,a;'

+EXPR_BEG

EXPR_BEG C "m" tIDENTIFIER EXPR_CMDARG

EXPR_CMDARG S "a" tIDENTIFIER EXPR_ARG

1:cmd push-

EXPR_ARG "(" '(' EXPR_BEG

0:cond push

10:cmd push

EXPR_BEG C ")" ')' EXPR_END

0:cond lexpop

1:cmd lexpop

EXPR_END "," ',' EXPR_BEG

EXPR_BEG "a" tIDENTIFIER EXPR_ARG

EXPR_ARG "," ',' EXPR_BEG

EXPR_BEG "a" tIDENTIFIER EXPR_ARG

EXPR_ARG ";" ';' EXPR_BEG

0:cmd resume

EXPR_BEG C "\n" ' EXPR_BEG

When the first terminal symbol of the first parameter has been read, `CMDARG_P()` is true. Therefore, the complete answer would be:

From the first terminal symbol of the first parameter of a method call with parentheses omitted To the terminal symbol following the final parameter

What repercussions does this fact have? Recall the code that uses `CMDARG_P()`

▼ `yylex`-Identifiers-Reserved words-`kDO`-`kDO_BLOCK`

4185 if (CMDARG_P() && state != EXPR_CMDARG) 4186 return kDO_BLOCK;(parse.y)

`EXPR_CMDARG` stands for “Before the first parameter of `command_call`” and is excluded. But wait, this meaning is also included in `CMDARG_P()`. Thus, the final conclusion of this section:

EXPR_CMDARG is completely useless

Truth be told, when I realized this, I almost broke down crying. I was sure it had to mean SOMETHING and spent enormous effort analyzing the source, but couldn’t understand anything. Finally, I ran all kind of tests on the code using `rubylex-analyser` and arrived at the conclusion that it has no meaning whatsoever.

I didn’t spend so much time doing something meaningless just to fill up more pages. It was an attempt to simulate a situation likely to happen in reality. No program is perfect, all programs contain their own mistakes. Complicated situations like the one discussed here are where mistakes occur most easily, and when they do, reading the source material with the assumption that it’s flawless can really backfire. In the end, when reading the source code, you can only trust the what actually happens.

Hopefully, this will teach you the importance of dynamic analysis. When investigating something, focus on what really happens. The source code will not tell you everything. It can’t tell anything other than what the reader infers.

And with this very useful sermon, I close the chapter.

((errata:

This confidently written conclusion was wrong.

Without `EXPR_CMDARG`, for instance, this program “`m (m do end)`” cannot be

parsed. This is an example of the fact that correctness is not proved even if

dynamic analyses are done so many times.

))

Still not the end

Another thing I forgot. I can’t end the chapter without explaining why `CMDARG_P()` takes that value. Here’s the problematic part:

▼ `command_args`

1209 command_args : {

1210 $$ = cmdarg_stack;

1211 CMDARG_PUSH(1);

1212 }

1213 open_args

1214 {

1215 /* CMDARG_POP() */

1216 cmdarg_stack = $1;

1217 $$ = $2;

1218 }

1221 open_args : call_args

(parse.y)

All things considered, this looks like another influence from lookahead. `command_args` is always in the following context:

tIDENTIFIER _

Thus, this looks like a variable reference or a method call. If it’s a variable reference, it needs to be reduced to `variable` and if it’s a method call it needs to be reduced to `operation` We cannot decide how to proceed without employing lookahead. Thus a lookahead always occurs at the head of `command_args` and after the first terminal symbol of the first parameter is read, `CMDARG_PUSH()` is executed.

The reason why `POP` and `LEXPOP` exist separately in `cmdarg_stack` is also here. Observe the following example:

% rubylex-analyser -e 'm m (a), a'

-e:1: warning: parenthesize argument(s) for future version

+EXPR_BEG

EXPR_BEG C "m" tIDENTIFIER EXPR_CMDARG

EXPR_CMDARG S "m" tIDENTIFIER EXPR_ARG

1:cmd push-

EXPR_ARG S "(" tLPAREN_ARG EXPR_BEG

0:cond push

10:cmd push

101:cmd push-

EXPR_BEG C "a" tIDENTIFIER EXPR_CMDARG

EXPR_CMDARG ")" ')' EXPR_END

0:cond lexpop

11:cmd lexpop

+EXPR_ENDARG

EXPR_ENDARG "," ',' EXPR_BEG

EXPR_BEG S "a" tIDENTIFIER EXPR_ARG

EXPR_ARG "\n" \n EXPR_BEG

10:cmd resume

0:cmd resume

Looking only at the parts related to `cmd` and how they correspond to each other…

1:cmd push- parserpush(1) 10:cmd push scannerpush 101:cmd push- parserpush(2) 11:cmd lexpop scannerpop 10:cmd resume parserpop(2) 0:cmd resume parserpop(1)

The `cmd push-` with a minus sign at the end is a parser push. Basically, `push` and `pop` do not correspond. Originally there were supposed to be two consecutive `push-` and the stack would become 110, but due to the lookahead the stack became 101 instead. `CMDARG_LEXPOP()` is a last-resort measure to deal with this. The scanner always pushes 0 so normally what it pops should also always be 0. When it isn’t 0, we can only assume that it’s 1 due to the parser `push` being late. Thus, the value is left.

Conversely, at the time of the parser `pop` the stack is supposed to be back in normal state and usually `pop` shouldn’t cause any trouble. When it doesn’t do that, the reason is basically that it should work right. Whether popping or hiding in `$$` and restoring, the process is the same. When you consider all the following alterations, it’s really impossible to tell how lookahead’s behavior will change. Moreover, this problem appears in a grammar that’s going to be forbidden in the future (that’s why there is a warning). To make something like this work, the trick is to consider numerous possible situations and respond them. And that is why I think this kind of implementation is right for Ruby. Therein lies the real solution.