Ruby Hacking Guide

Translated by Sebastian Krause & ocha-

Chapter 5: Garbage Collection

A conception of an executing program

It’s all of a sudden but at the beginning of this chapter, we’ll learn about the memory space of an executing program. In this chapter we’ll step inside the lower level parts of a computer quite a bit, so without preliminary knowledge it’ll be hard to follow. And it’ll be also necessary for the following chapters. Once we finish this here, the rest will be easier.

Memory Segments

A general C program has the following parts in the memory space:

- the text area

- a place for static and global variables

- the machine stack

- the heap

The text area is where the code lies. Obviously the second area holds static and global variables. Arguments and local variables of functions are piling up in the machine stack. The heap is the place where allocated by `malloc()`.

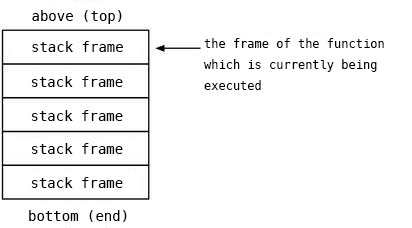

Let’s talk a bit more about number three, the machine stack. Since it is called the machine “stack”, obviously it has a stack structure. In other words, new stuff is piled on top of it one after another. When we actually pushes values on the stack, each value would be a tiny piece such as `int`. But logically, there are a little larger pieces. They are called stack frames.

One stack frame corresponds to one function call. Or in other words when there is a function call, one stack frame is pushed. When doing `return`, one stack frame will be popped. Figure 1 shows the really simplified appearance of the machine stack.

In this picture, “above” is written above the top of the stack, but this it is not necessarily always the case that the machine stack goes from low addresses to high addresses. For instance, on the x86 machine the stack goes from high to low addresses.

`alloca()`

By using `malloc()`, we can get an arbitrarily large memory area of the heap. `alloca()` is the machine stack version of it. But unlike `malloc()` it’s not necessary to free the memory allocated with `alloca()`. Or one should say: it is freed automatically at the same moment of `return` of each function. That’s why it’s not possible to use an allocated value as the return value. It’s the same as “You must not return the pointer to a local variable.”

There’s been not any difficulty. We can consider it something to locally allocate an array whose size can be changed at runtime.

However there exist environments where there is no native `alloca()`.

There are still many who would like to use `alloca()` even if in such

environment, sometimes a function to do the same thing is written in C.

But in that case, only the feature that we don’t have to free it by ourselves

is implemented and it does not necessarily allocate the memory on the machine

stack. In fact, it often does not.

If it were possible, a native

alloca() could have been implemented in the first place.

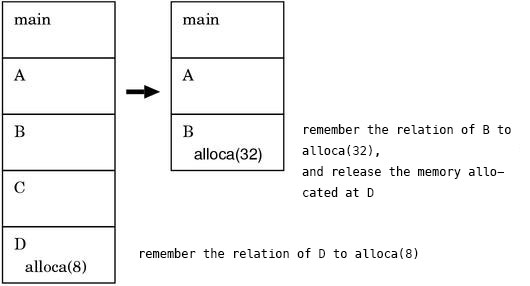

How can one implement alloca() in C? The simplest implementation is:

first allocate memory normally with malloc(). Then remember the pair of the function

which called alloca() and the assigned addresses in a global list.

After that, check this list whenever alloca() is called,

if there are the memories allocated for the functions already finished,

free them by using `free()`.

The missing/alloca.c of ruby is an example of an emulated alloca() .

Overview

From here on we can at last talk about the main subject of this chapter: garbage collection.

What is GC?

Objects are normally on top of the memory. Naturally, if a lot of objects are created, a lot of memory is used. If memory

were infinite there would be no problem, but in reality there is always a memory

limit. That’s why the memory which is not

used anymore must be collected and recycled. More concretely the memory received through malloc() must be returned with

free().

However, it would require a lot of efforts if the management of `malloc()` and `free()` were entirely left to programmers. Especially in object oriented programs, because objects are referring each other, it is difficult to tell when to release memory.

There garbage collection comes in. Garbage Collection (GC) is a feature to automatically detect and free the memory which has become unnecessary. With garbage collection, the worry “When should I have to `free()` ??” has become unnecessary. Between when it exists and when it does not exist, the ease of writing programs differs considerably.

By the way, in a book about something that I’ve read, there’s a description “the thing to tidy up the fragmented usable memory is GC”. This task is called “compaction”. It is compaction because it makes a thing compact. Because compaction makes memory cache more often hit, it has effects for speed-up to some extent, but it is not the main purpose of GC. The purpose of GC is to collect memory. There are many GCs which collect memories but don’t do compaction. The GC of `ruby` also does not do compaction.

Then, in what kind of system is GC available? In C and C++, there’s Boehm GC\footnote{Boehm GC `http://www.hpl.hp.com/personal/Hans_Boehm/gc`} which can be used as an add-on. And, for the recent languages such as Java and Perl, Python, C#, Eiffel, GC is a standard equipment. And of course, Ruby has its GC. Let’s follow the details of `ruby`’s GC in this chapter. The target file is `gc.c`.

What does GC do?

Before explaining the GC algorithm, I should explain “what garbage collection is”. In other words, what kind of state of the memory is “the unnecessary memory”?

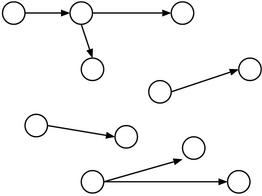

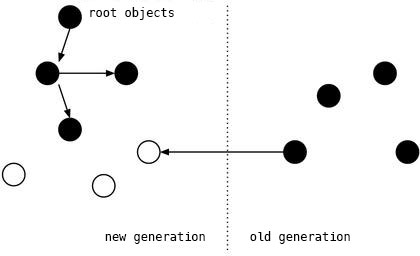

To make descriptions more concrete, let’s simplify the structure by assuming that there are only objects and links. This would look as shown in Figure 3.

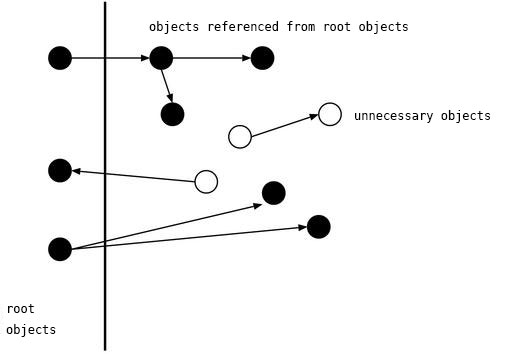

The objects pointed to by global variables and the objects on the stack of a language are surely necessary. And objects pointed to by instance variables of these objects are also necessary. Furthermore, the objects that are reachable by following links from these objects are also necessary.

To put it more logically, the necessary objects are all objects which can be reached recursively via links from the “surely necessary objects” as the start points. This is depicted in figure 4. What are on the left of the line are all “surely necessary objects”, and the objects which can be reached from them are colored black. These objects colored black are the necessary objects. The rest of the objects can be released.

In technical terms, “the surely necessary objects” are called “the roots of GC”. That’s because they are the roots of tree structures that emerges as a consequence of tracing necessary objects.

Mark and Sweep

GC was first implemented in Lisp. The GC implemented in Lisp at first, it means the world’s first GC, is called mark&sweep GC. The GC of `ruby` is one type of it.

The image of Mark-and-Sweep GC is pretty close to our definition of “necessary object”. First, put “marks” on the root objects. Setting them as the start points, put “marks” on all reachable objects. This is the mark phase.

At the moment when there’s not any reachable object left, check all objects in the object pool, release (sweep) all objects that have not marked. “Sweep” is the “sweep” of Minesweeper.

There are two advantages.

- There does not need to be any (or almost any) concern for garbage collection outside the implementation of GC.

- Cycles can also be released. (As for cycles, see also the section of “Reference Count”)

There are also two disadvantages.

- In order to sweep every object must be touched at least once.

- The load of the GC is concentrated at one point.

When using the emacs editor, there sometimes appears " Garbage collecting... "

and it completely stops reacting. That is an example of the second disadvantage.

But this point can be alleviated by modifying the algorithm (it is called incremental GC).

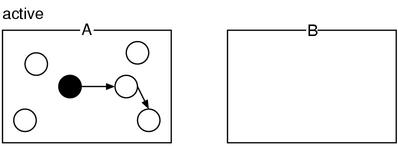

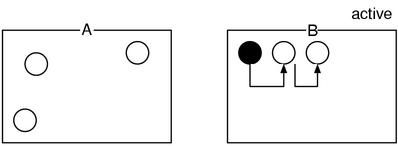

Stop and Copy

Stop and Copy is a variation of Mark and Sweep. First, prepare several object

areas. To simplify this description, assume there are two areas A and B here.

And put an “active” mark on the one of the areas.

When creating an object, create it only in the “active” one. (Figure 5)

When the GC starts, follow links from the roots in the same manner as

mark-and-sweep. However, move objects to another area instead of marking them

(Figure 6). When all the links have been followed, discard the all elements

which remain in A, and make B active next.

Stop and Copy also has two advantages:

- Compaction happens at the same time as collecting the memory

- Since objects that reference each other move closer together, there’s more possibility of hitting the cache.

And also two disadvantages:

- The object area needs to be more than twice as big

- The positions of objects will be changed

It seems what exist in this world are not only positive things.

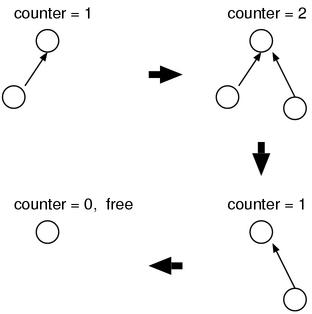

Reference counting

Reference counting differs a bit from the aforementioned GCs, the reach-check code is distributed in several places.

First, attach an integer count to each element. When referring via variables or arrays, the counter of the referenced object is increased. When quitting to refer, decrease the counter. When the counter of an object becomes zero, release the object. This is the method called reference counting (Figure 7).

This method also has two advantages:

- The load of GC is distributed over the entire program.

- The object that becomes unnecessary is immediately freed.

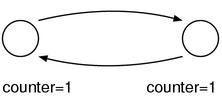

And also two disadvantages.

- The counter handling tends to be forgotten.

- When doing it naively cycles are not released.

I’ll explain about the second point just in case. A cycle is a cycle of references as shown in Figure 8. If this is the case the counters will never decrease and the objects will never be released.

By the way, latest Python(2.2) uses reference counting GC but it can free cycles. However, it is not because of the reference counting itself, but because it sometimes invokes mark and sweep GC to check.

Object Management

Ruby’s garbage collection is only concerned with ruby objects. Moreover, it only concerned with the objects created and managed by `ruby`. Conversely speaking, if the memory is allocated without following a certain procedure, it won’t be taken care of. For instance, the following function will cause a memory leak even if `ruby` is running.

void not_ok()

{

malloc(1024); /* receive memory and discard it */

}

However, the following function does not cause a memory leak.

void this_is_ok()

{

rb_ary_new(); /* create a ruby array and discard it */

}

Since rb_ary_new() uses Ruby’s proper interface to allocate memory,

the created object is under the management of the GC of `ruby`,

thus `ruby` will take care of it.

`struct RVALUE`

Since the substance of an object is a struct,

managing objects means managing that structs.

Of course the non-pointer objects like Fixnum Symbol nil true false are

exceptions, but I won’t always describe about it to prevent descriptions

from being redundant.

Each struct type has its different size, but probably in order to keep management simpler, a union of all the structs of built-in classes is declared and the union is always used when dealing with memory. The declaration of that union is as follows.

▼ `RVALUE`

211 typedef struct RVALUE {

212 union {

213 struct {

214 unsigned long flags; /* 0 if not used */

215 struct RVALUE *next;

216 } free;

217 struct RBasic basic;

218 struct RObject object;

219 struct RClass klass;

220 struct RFloat flonum;

221 struct RString string;

222 struct RArray array;

223 struct RRegexp regexp;

224 struct RHash hash;

225 struct RData data;

226 struct RStruct rstruct;

227 struct RBignum bignum;

228 struct RFile file;

229 struct RNode node;

230 struct RMatch match;

231 struct RVarmap varmap;

232 struct SCOPE scope;

233 } as;

234 } RVALUE;

(gc.c)

`struct RVALUE` is a struct that has only one element. I’ve heard that the reason why `union` is not directly used is to enable to easily increase its members when debugging or when extending in the future.

First, let’s focus on the first element of the union `free.flags`. The comment says “`0` if not used”, but is it true? Is there not any possibility for `free.flags` to be `0` by chance?

As we’ve seen in Chapter 2: Objects, all object structs have `struct RBasic` as its first element. Therefore, by whichever element of the union we access, `obj→as.free.flags` means the same as it is written as `obj→as.basic.flags`. And objects always have the struct-type flag (such as `T_STRING`), and the flag is always not `0`. Therefore, the flag of an “alive” object will never coincidentally be `0`. Hence, we can confirm that setting their flags to `0` is necessity and sufficiency to represent “dead” objects.

Object heap

The memory for all the object structs has been brought together in global variable `heaps`. Hereafter, let’s call this an object heap.

▼ Object heap

239 #define HEAPS_INCREMENT 10 240 static RVALUE **heaps; 241 static int heaps_length = 0; 242 static int heaps_used = 0; 243 244 #define HEAP_MIN_SLOTS 10000 245 static int *heaps_limits; 246 static int heap_slots = HEAP_MIN_SLOTS; (gc.c)

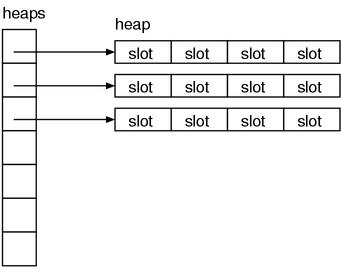

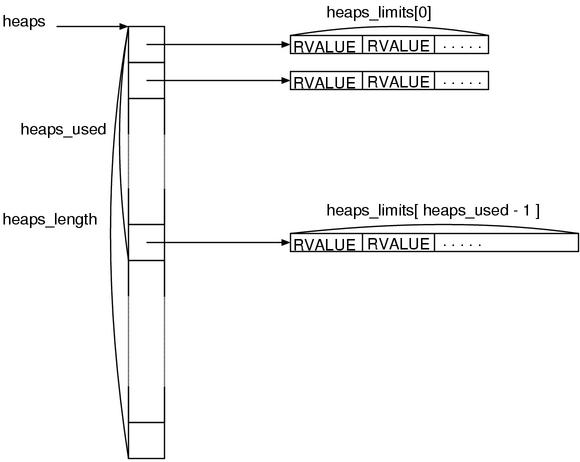

heaps is an array of arrays of struct RVALUE. Since it is `heapS`,

the each contained array is probably each heap.

Each element of heap is each slot (Figure 9).

The length of heaps is heap_length and it can be changed. The number of

the slots actually in use is heaps_used. The length of each heap

is in the corresponding heaps_limits[index].

Figure 10 shows the structure of the object heap.

This structure has a necessity to be this way. For instance, if all structs are stored in an array, the memory space would be the most compact, but we cannot do `realloc()` because it could change the addresses. This is because `VALUE`s are mere pointers.

In the case of an implementation of Java, the counterpart of `VALUE`s are not addresses but the indexes of objects. Since they are handled through a pointer table, objects are movable. However in this case, indexing of the array comes in every time an object access occurs and it lowers the performance in some degree.

On the other hand, what happens if it is an one-dimensional array of pointers to `RVALUE`s (it means `VALUE`s)? This seems to be able to go well at the first glance, but it does not when GC. That is, as I’ll describe in detail, the GC of `ruby` needs to know the integers "which seems `VALUE` (the pointers to `RVALUE`). If all `RVALUE` are allocated in addresses which are far from each other, it needs to compare all address of `RVALUE` with all integers “which could be pointers”. This means the time for GC becomes the order more than O(n^2), and not acceptable.

According to these requirements, it is good that the object heap form a structure that the addresses are cohesive to some extent and whose position and total amount are not restricted at the same time.

`freelist`

Unused `RVALUE`s are managed by being linked as a single line which is a linked list that starts with `freelist`. The `as.free.next` of `RVALUE` is the link used for this purpose.

▼ `freelist`

236 static RVALUE *freelist = 0; (gc.c)

`add_heap()`

As we understood the data structure, let’s read the function `add_heap()` to add a heap. Because this function contains a lot of lines not part of the main line, I’ll show the one simplified by omitting error handlings and castings.

▼ `add_heap()` (simplified)

static void

add_heap()

{

RVALUE *p, *pend;

/* extend heaps if necessary */

if (heaps_used == heaps_length) {

heaps_length += HEAPS_INCREMENT;

heaps = realloc(heaps, heaps_length * sizeof(RVALUE*));

heaps_limits = realloc(heaps_limits, heaps_length * sizeof(int));

}

/* increase heaps by 1 */

p = heaps[heaps_used] = malloc(sizeof(RVALUE) * heap_slots);

heaps_limits[heaps_used] = heap_slots;

pend = p + heap_slots;

if (lomem == 0 || lomem > p) lomem = p;

if (himem < pend) himem = pend;

heaps_used++;

heap_slots *= 1.8;

/* link the allocated RVALUE to freelist */

while (p < pend) {

p->as.free.flags = 0;

p->as.free.next = freelist;

freelist = p;

p++;

}

}

Please check the following points.

- the length of `heap` is `heap_slots`

- the `heap_slots` becomes 1.8 times larger every time when a `heap` is added

- the length of `heaps[i]` (the value of `heap_slots` when creating a heap) is stored in `heaps_limits[i]`.

Plus, since `lomem` and `himem` are modified only by this function, only by this function you can understand the mechanism. These variables hold the lowest and the highest addresses of the object heap. These values are used later when determining the integers “which seems `VALUE`”.

`rb_newobj()`

Considering all of the above points, we can tell the way to create an object in a second. If there is at least a `RVALUE` linked from `freelist`, we can use it. Otherwise, do GC or increase the heaps. Let’s confirm this by reading the `rb_newobj()` function to create an object.

▼ `rb_newobj()`

297 VALUE

298 rb_newobj()

299 {

300 VALUE obj;

301

302 if (!freelist) rb_gc();

303

304 obj = (VALUE)freelist;

305 freelist = freelist->as.free.next;

306 MEMZERO((void*)obj, RVALUE, 1);

307 return obj;

308 }

(gc.c)

If `freelest` is 0, in other words, if there’s not any unused structs, invoke GC and create spaces. Even if we could not collect not any object, there’s no problem because in this case a new space is allocated in `rb_gc()`. And take a struct from `freelist`, zerofill it by `MEMZERO()`, and return it.

Mark

As described, `ruby`’s GC is Mark & Sweep. Its “mark” is, concretely speaking, to set a `FL_MARK` flag: look for unused `VALUE`, set `FL_MARK` flags to found ones, then look at the object heap after investigating all and free objects that `FL_MARK` has not been set.

`rb_gc_mark()`

`rb_gc_mark()` is the function to mark objects recursively.

▼ `rb_gc_mark()`

573 void

574 rb_gc_mark(ptr)

575 VALUE ptr;

576 {

577 int ret;

578 register RVALUE *obj = RANY(ptr);

579

580 if (rb_special_const_p(ptr)) return; /* special const not marked */

581 if (obj->as.basic.flags == 0) return; /* free cell */

582 if (obj->as.basic.flags & FL_MARK) return; /* already marked */

583

584 obj->as.basic.flags |= FL_MARK;

585

586 CHECK_STACK(ret);

587 if (ret) {

588 if (!mark_stack_overflow) {

589 if (mark_stack_ptr - mark_stack < MARK_STACK_MAX) {

590 *mark_stack_ptr = ptr;

591 mark_stack_ptr++;

592 }

593 else {

594 mark_stack_overflow = 1;

595 }

596 }

597 }

598 else {

599 rb_gc_mark_children(ptr);

600 }

601 }

(gc.c)

The definition of RANY() is as follows. It is not particularly important.

▼ `RANY()`

295 #define RANY(o) ((RVALUE*)(o)) (gc.c)

There are the checks for non-pointers or already freed objects and the recursive checks for marked objects at the beginning,

obj->as.basic.flags |= FL_MARK;

and `obj` (this is the `ptr` parameter of this function) is marked. Then next, it’s the turn to follow the references from `obj` and mark. `rb_gc_mark_children()` does it.

The others, what starts with `CHECK_STACK()` and is written a lot is a device to prevent the machine stack overflow. Since `rb_gc_mark()` uses recursive calls to mark objects, if there is a big object cluster, it is possible to run short of the length of the machine stack. To counter that, if the machine stack is nearly overflow, it stops the recursive calls, piles up the objects on a global list, and later it marks them once again. This code is omitted because it is not part of the main line.

`rb_gc_mark_children()`

Now, as for `rb_gc_mark_children()`, it just lists up the internal types and marks one by one, thus it is not just long but also not interesting. Here, it is shown but the simple enumerations are omitted:

▼ `rb_gc_mark_children()`

603 void

604 rb_gc_mark_children(ptr)

605 VALUE ptr;

606 {

607 register RVALUE *obj = RANY(ptr);

608

609 if (FL_TEST(obj, FL_EXIVAR)) {

610 rb_mark_generic_ivar((VALUE)obj);

611 }

612

613 switch (obj->as.basic.flags & T_MASK) {

614 case T_NIL:

615 case T_FIXNUM:

616 rb_bug("rb_gc_mark() called for broken object");

617 break;

618

619 case T_NODE:

620 mark_source_filename(obj->as.node.nd_file);

621 switch (nd_type(obj)) {

622 case NODE_IF: /* 1,2,3 */

623 case NODE_FOR:

624 case NODE_ITER:

/* ………… omitted ………… */

749 }

750 return; /* not need to mark basic.klass */

751 }

752

753 rb_gc_mark(obj->as.basic.klass);

754 switch (obj->as.basic.flags & T_MASK) {

755 case T_ICLASS:

756 case T_CLASS:

757 case T_MODULE:

758 rb_gc_mark(obj->as.klass.super);

759 rb_mark_tbl(obj->as.klass.m_tbl);

760 rb_mark_tbl(obj->as.klass.iv_tbl);

761 break;

762

763 case T_ARRAY:

764 if (FL_TEST(obj, ELTS_SHARED)) {

765 rb_gc_mark(obj->as.array.aux.shared);

766 }

767 else {

768 long i, len = obj->as.array.len;

769 VALUE *ptr = obj->as.array.ptr;

770

771 for (i=0; i < len; i++) {

772 rb_gc_mark(*ptr++);

773 }

774 }

775 break;

/* ………… omitted ………… */

837 default:

838 rb_bug("rb_gc_mark(): unknown data type 0x%x(0x%x) %s",

839 obj->as.basic.flags & T_MASK, obj,

840 is_pointer_to_heap(obj) ? "corrupted object"

: "non object");

841 }

842 }

(gc.c)

It calls `rb_gc_mark()` recursively, is only what I’d like you to confirm. In the omitted part, `NODE` and `T_xxxx` are enumerated respectively. `NODE` will be introduced in Part 2.

Additionally, let’s see the part to mark `T_DATA` (the struct used for extension libraries) because there’s something we’d like to check. This code is extracted from the second `switch` statement.

▼ `rb_gc_mark_children()` – `T_DATA`

789 case T_DATA: 790 if (obj->as.data.dmark) (*obj->as.data.dmark)(DATA_PTR(obj)); 791 break; (gc.c)

Here, it does not use `rb_gc_mark()` or similar functions, but the `dmark` which is given from users. Inside it, of course, it might use `rb_gc_mark()` or something, but not using is also possible. For example, in an extreme situation, if a user defined object does not contain `VALUE`, there’s no need to mark.

`rb_gc()`

By now, we’ve finished to talk about each object. From now on, let’s see the function `rb_gc()` that presides the whole. The objects marked here are “objects which are obviously necessary”. In other words, “the roots of GC”.

▼ `rb_gc()`

1110 void

1111 rb_gc()

1112 {

1113 struct gc_list *list;

1114 struct FRAME * volatile frame; /* gcc 2.7.2.3 -O2 bug?? */

1115 jmp_buf save_regs_gc_mark;

1116 SET_STACK_END;

1117

1118 if (dont_gc || during_gc) {

1119 if (!freelist) {

1120 add_heap();

1121 }

1122 return;

1123 }

/* …… mark from the all roots …… */

1183 gc_sweep();

1184 }

(gc.c)

The roots which should be marked will be shown one by one after this, but I’d like to mention just one point here.

In `ruby` the CPU registers and the machine stack are also the roots. It means that the local variables and arguments of C are automatically marked. For example,

static int

f(void)

{

VALUE arr = rb_ary_new();

/* …… do various things …… */

}

like this way, we can protect an object just by putting it into a variable. This is a very significant trait of the GC of `ruby`. Because of this feature, `ruby`’s extension libraries are insanely easy to write.

However, what is on the stack is not only `VALUE`. There are a lot of totally unrelated values. How to resolve this is the key when reading the implementation of GC.

The Ruby Stack

First, it marks the (`ruby`‘s) stack frames used by the interpretor. Since you will be able to find out who it is after reaching Part 3, you don’t have to think so much about it for now.

▼ Marking the Ruby Stack

1130 /* mark frame stack */

1131 for (frame = ruby_frame; frame; frame = frame->prev) {

1132 rb_gc_mark_frame(frame);

1133 if (frame->tmp) {

1134 struct FRAME *tmp = frame->tmp;

1135 while (tmp) {

1136 rb_gc_mark_frame(tmp);

1137 tmp = tmp->prev;

1138 }

1139 }

1140 }

1141 rb_gc_mark((VALUE)ruby_class);

1142 rb_gc_mark((VALUE)ruby_scope);

1143 rb_gc_mark((VALUE)ruby_dyna_vars);

(gc.c)

`ruby_frame ruby_class ruby_scope ruby_dyna_vars` are the variables to point to each top of the stacks of the evaluator. These hold the frame, the class scope, the local variable scope, and the block local variables at that time respectively.

Register

Next, it marks the CPU registers.

▼ marking the registers

1148 FLUSH_REGISTER_WINDOWS;

1149 /* Here, all registers must be saved into jmp_buf. */

1150 setjmp(save_regs_gc_mark);

1151 mark_locations_array((VALUE*)save_regs_gc_mark,

sizeof(save_regs_gc_mark) / sizeof(VALUE *));

(gc.c)

`FLUSH_REGISTER_WINDOWS` is special. We will see it later.

`setjmp()` is essentially a function to remotely jump, but the content of the registers are saved into the argument (which is a variable of type `jmp_buf`) as its side effect. Making use of this, it attempts to mark the content of the registers. Things around here really look like secret techniques.

However only `djgpp` and `Human68k` are specially treated. djgpp is a `gcc` environment for DOS. Human68k is an OS of SHARP X680x0 Series. In these two environments, the whole registers seem to be not saved only by the ordinary `setjmp()`, `setjmp()` is redefined as follows as an inline-assembler to explicitly write out the registers.

▼ the original version of `setjmp`

1072 #ifdef __GNUC__

1073 #if defined(__human68k__) || defined(DJGPP)

1074 #if defined(__human68k__)

1075 typedef unsigned long rb_jmp_buf[8];

1076 __asm__ (".even\n\ 2-byte alignment

1077 _rb_setjmp:\n\ the label of rb_setjmp() function

1078 move.l 4(sp),a0\n\ load the first argument to the a0 register

1079 movem.l d3-d7/a3-a5,(a0)\n\ copy the registers to where a0 points to

1080 moveq.l #0,d0\n\ set 0 to d0 (as the return value)

1081 rts"); return

1082 #ifdef setjmp

1083 #undef setjmp

1084 #endif

1085 #else

1086 #if defined(DJGPP)

1087 typedef unsigned long rb_jmp_buf[6];

1088 __asm__ (".align 4\n\ order 4-byte alignment

1089 _rb_setjmp:\n\ the label for rb_setjmp() function

1090 pushl %ebp\n\ push ebp to the stack

1091 movl %esp,%ebp\n\ set the stack pointer to ebp

1092 movl 8(%ebp),%ebp\n\ pick up the first argument and set to ebp

1093 movl %eax,(%ebp)\n\ in the followings, store each register

1094 movl %ebx,4(%ebp)\n\ to where ebp points to

1095 movl %ecx,8(%ebp)\n\

1096 movl %edx,12(%ebp)\n\

1097 movl %esi,16(%ebp)\n\

1098 movl %edi,20(%ebp)\n\

1099 popl %ebp\n\ restore ebp from the stack

1100 xorl %eax,%eax\n\ set 0 to eax (as the return value)

1101 ret"); return

1102 #endif

1103 #endif

1104 int rb_setjmp (rb_jmp_buf);

1105 #define jmp_buf rb_jmp_buf

1106 #define setjmp rb_setjmp

1107 #endif /* __human68k__ or DJGPP */

1108 #endif /* __GNUC__ */

(gc.c)

Alignment is the constraint when putting variables on memories. For example, in 32-bit machine `int` is usually 32 bits, but we cannot always take 32 bits from anywhere of memories. Particularly, RISC machine has strict constraints, it is decided like “from a multiple of 4 byte” or “from even byte”. When there are such constraints, memory access unit can be more simplified (thus, it can be faster). When there’s the constraint of “from a multiple of 4 byte”, it is called “4-byte alignment”.

Plus, in `cc` of djgpp or Human68k, there’s a rule that the compiler put the underline to the head of each function name. Therefore, when writing a C function in Assembler, we need to put the underline (`_`) to its head by ourselves. This type of constraints are techniques in order to avoid the conflicts in names with library functions. Also in UNIX, it is said that the underline had been attached by some time ago, but it almost disappears now.

Now, the content of the registers has been able to be written out into `jmp_buf`, it will be marked in the next code:

▼ mark the registers (shown again)

1151 mark_locations_array((VALUE*)save_regs_gc_mark,

sizeof(save_regs_gc_mark) / sizeof(VALUE *));

(gc.c)

This is the first time that `mark_locations_array()` appears. I’ll describe it in the next section.

`mark_locations_array()`

▼ `mark_locations_array()`

500 static void

501 mark_locations_array(x, n)

502 register VALUE *x;

503 register long n;

504 {

505 while (n--) {

506 if (is_pointer_to_heap((void *)*x)) {

507 rb_gc_mark(*x);

508 }

509 x++;

510 }

511 }

(gc.c)

This function is to mark the all elements of an array, but it slightly differs from the previous mark functions. Until now, each place to be marked is where we know it surely holds a `VALUE` (a pointer to an object). However this time, where it attempts to mark is the register space, it is enough to expect that there’re also what are not `VALUE`. To counter that, it tries to detect whether or not the value is a `VALUE` (a pointer), then if it seems, the value will be handled as a pointer. This kind of methods are called “conservative GC”. It seems that it is conservative because it “tentatively inclines things to the safe side”

Next, we’ll look at the function to check if “it looks like a `VALUE`”, it is `is_pointer_to_heap()`.

`is_pointer_to_heap()`

▼ `is_pointer_to_heap()`

480 static inline int

481 is_pointer_to_heap(ptr)

482 void *ptr;

483 {

484 register RVALUE *p = RANY(ptr);

485 register RVALUE *heap_org;

486 register long i;

487

488 if (p < lomem || p > himem) return Qfalse;

489

490 /* check if there's the possibility that p is a pointer */

491 for (i=0; i < heaps_used; i++) {

492 heap_org = heaps[i];

493 if (heap_org <= p && p < heap_org + heaps_limits[i] &&

494 ((((char*)p)-((char*)heap_org))%sizeof(RVALUE)) == 0)

495 return Qtrue;

496 }

497 return Qfalse;

498 }

(gc.c)

If I briefly explain it, it would look like the followings:

- check if it is in between the top and the bottom of the addresses where `RVALUE`s reside.

- check if it is in the range of a heap

- make sure the value points to the head of a `RVALUE`.

Since the mechanism is like this, it’s obviously possible that a non-`VALUE` value is mistakenly handled as a `VALUE`. But at least, it will never fail to find out the used `VALUE`s. And, with this amount of tests, it may rarely pick up a non-`VALUE` value unless it intentionally does. Therefore, considering about the benefits we can obtain by GC, it’s sufficient to compromise.

Register Window

This section is about `FLUSH_REGISTER_WINDOWS()` which has been deferred.

Register windows are the mechanism to enable to put a part of the machine stack into inside the CPU. In short, it is a cache whose purpose of use is narrowed down. Recently, it exists only in Sparc architecture. It’s possible that there are also `VALUE`s in register windows, and it’s also necessary to get down them into memory.

The content of the macro is like this:

▼ `FLUSH_REGISTER_WINDOWS`

125 #if defined(sparc) || defined(__sparc__)

126 # if defined(linux) || defined(__linux__)

127 #define FLUSH_REGISTER_WINDOWS asm("ta 0x83")

128 # else /* Solaris, not sparc linux */

129 #define FLUSH_REGISTER_WINDOWS asm("ta 0x03")

130 # endif

131 #else /* Not a sparc */

132 #define FLUSH_REGISTER_WINDOWS

133 #endif

(defines.h)

`asm(…)` is a built-in assembler. However, even though I call it assembler, this instruction named `ta` is the call of a privileged instruction. In other words, the call is not of the CPU but of the OS. That’s why the instruction is different for each OS. The comments describe only about Linux and Solaris, but actually FreeBSD and NetBSD are also works on Sparc, so this comment is wrong.

Plus, if it is not Sparc, it is unnecessary to flush, thus `FLUSH_REGISTER_WINDOWS` is defined as nothing. Like this, the method to get a macro back to nothing is very famous technique that is also convenient when debugging.

Machine Stack

Then, let’s go back to the rest of `rb_gc()`. This time, it marks `VALUES`s in the machine stack.

▼ mark the machine stack

1152 rb_gc_mark_locations(rb_gc_stack_start, (VALUE*)STACK_END); 1153 #if defined(__human68k__) 1154 rb_gc_mark_locations((VALUE*)((char*)rb_gc_stack_start + 2), 1155 (VALUE*)((char*)STACK_END + 2)); 1156 #endif (gc.c)

`rb_gc_stack_start` seems the start address (the end of the stack) and `STACK_END` seems the end address (the top). And, `rb_gc_mark_locations()` practically marks the stack space.

There are `rb_gc_mark_locations()` two times in order to deal with the architectures which are not 4-byte alignment. `rb_gc_mark_locations()` tries to mark for each portion of `sizeof(VALUE)`, so if it is in 2-byte alignment environment, sometimes not be able to properly mark. In this case, it moves the range 2 bytes then marks again.

Now, `rb_gc_stack_start`, `STACK_END`, `rb_gc_mark_locations()`, let’s examine these three in this order.

`Init_stack()`

The first thing is `rb_gc_starck_start`. This variable is set only during `Init_stack()`. As the name `Init_` might suggest, this function is called at the time when initializing the `ruby` interpretor.

▼ `Init_stack()`

1193 void

1194 Init_stack(addr)

1195 VALUE *addr;

1196 {

1197 #if defined(__human68k__)

1198 extern void *_SEND;

1199 rb_gc_stack_start = _SEND;

1200 #else

1201 VALUE start;

1202

1203 if (!addr) addr = &start;

1204 rb_gc_stack_start = addr;

1205 #endif

1206 #ifdef HAVE_GETRLIMIT

1207 {

1208 struct rlimit rlim;

1209

1210 if (getrlimit(RLIMIT_STACK, &rlim) == 0) {

1211 double space = (double)rlim.rlim_cur*0.2;

1212

1213 if (space > 1024*1024) space = 1024*1024;

1214 STACK_LEVEL_MAX = (rlim.rlim_cur - space) / sizeof(VALUE);

1215 }

1216 }

1217 #endif

1218 }

(gc.c)

What is important is only the part in the middle. It defines an arbitrary local variable (it is allocated on the stack) and it sets its address to `rb_gc_stack_start`. The `SEND` inside the code for `_human68k__` is probably the variable defined by a library of compiler or system. Naturally, you can presume that it is the contraction of `Stack END`.

Meanwhile, the code after that bundled by `HAVE_GETRLIMIT` appears to check the length of the stack and do mysterious things. This is also in the same context of what is done at `rb_gc_mark_children()` to prevent the stack overflow. We can ignore this.

`STACK_END`

Next, we’ll look at the `STACK_END` which is the macro to detect the end of the stack.

▼ `STACK_END`

345 #ifdef C_ALLOCA 346 # define SET_STACK_END VALUE stack_end; alloca(0); 347 # define STACK_END (&stack_end) 348 #else 349 # if defined(__GNUC__) && defined(USE_BUILTIN_FRAME_ADDRESS) 350 # define SET_STACK_END VALUE *stack_end = __builtin_frame_address(0) 351 # else 352 # define SET_STACK_END VALUE *stack_end = alloca(1) 353 # endif 354 # define STACK_END (stack_end) 355 #endif (gc.c)

As there are three variations of `SET_STACK_END`, let’s start with the bottom one. `alloca()` allocates a space at the end of the stack and returns it, so the return value and the end address of the stack should be very close. Hence, it considers the return value of `alloca()` as an approximate value of the end of the stack.

Let’s go back and look at the one at the top. When the macro `C_ALLOCA` is defined, `alloca()` is not natively defined, … in other words, it indicates a compatible function is defined in C. I mentioned that in this case `alloca()` internally allocates memory by using `malloc()`. However, it does not help to get the position of the stack at all. To deal with this situation, it determines that the local variable `stack_end` of the currently executing function is close to the end of the stack and uses its address (`&stack_end`).

Plus, this code contains `alloca(0)` whose purpose is not easy to see. This has been a feature of the `alloca()` defined in C since early times, and it means “please check and free the unused space”. Since this is used when doing GC, it attempts to free the memory allocated with `alloca()` at the same time. But I think it’s better to put it in another macro instead of mixing into such place …

And at last, in the middle case, it is about `builtin_frame_address()`. `GNUC__` is a symbol defined in `gcc` (the compiler of GNU C). Since this is used to limit, it is a built-in instruction of `gcc`. You can get the address of the n-times previous stack frame with `builtin_frame_address(n)`. As for `builtin_frame_adress(0)`, it provides the address of the current frame.

`rb_gc_mark_locations()`

The last one is the `rb_gc_mark_locations()` function that actually marks the stack.

▼ `rb_gc_mark_locations()`

513 void

514 rb_gc_mark_locations(start, end)

515 VALUE *start, *end;

516 {

517 VALUE *tmp;

518 long n;

519

520 if (start > end) {

521 tmp = start;

522 start = end;

523 end = tmp;

524 }

525 n = end - start + 1;

526 mark_locations_array(start,n);

527 }

(gc.c)

Basically, delegating to the function `mark_locations_array()` which marks a space is sufficient. What this function does is properly adjusting the arguments. Such adjustment is required because in which direction the machine stack extends is undecided. If the machine stack extends to lower addresses, `end` is smaller, if it extends to higher addresses, `start` is smaller. Therefore, so that the smaller one becomes `start`, they are adjusted here.

The other root objects

Finally, it marks the built-in `VALUE` containers of the interpretor.

▼ The other roots

1159 /* mark the registered global variables */

1160 for (list = global_List; list; list = list->next) {

1161 rb_gc_mark(*list->varptr);

1162 }

1163 rb_mark_end_proc();

1164 rb_gc_mark_global_tbl();

1165

1166 rb_mark_tbl(rb_class_tbl);

1167 rb_gc_mark_trap_list();

1168

1169 /* mark the instance variables of true, false, etc if exist */

1170 rb_mark_generic_ivar_tbl();

1171

/* mark the variables used in the ruby parser (only while parsing) */

1172 rb_gc_mark_parser();

(gc.c)

When putting a `VALUE` into a global variable of C, it is required to register its address by user via `rb_gc_register_address()`. As these objects are saved in `global_List`, all of them are marked.

`rb_mark_end_proc()` is to mark the procedural objects which are registered via kind of `END` statement of Ruby and executed when a program finishes. (`END` statements will not be described in this book).

`rb_gc_mark_global_tbl()` is to mark the global variable table `rb_global_tbl`. (See also the next chapter “Variables and Constants”)

`rb_mark_tbl(rb_class_tbl)` is to mark `rb_class_tbl` which was discussed in the previous chapter.

`rb_gc_mark_trap_list()` is to mark the procedural objects which are registered via the Ruby’s function-like method `trap`. (This is related to signals and will also not be described in this book.)

`rb_mark_generic_ivar_tbl()` is to mark the instance variable table prepared for non-pointer `VALUE` such as `true`.

`rb_gc_mark_parser()` is to mark the semantic stack of the parser. (The semantic stack will be described in Part 2.)

Until here, the mark phase has been finished.

Sweep

The special treatment for `NODE`

The sweep phase is the procedures to find out and free the not-marked objects. But, for some reason, the objects of type `T_NODE` are specially treated. Take a look at the next part:

▼ at the beggining of `gc_sweep()`

846 static void

847 gc_sweep()

848 {

849 RVALUE *p, *pend, *final_list;

850 int freed = 0;

851 int i, used = heaps_used;

852

853 if (ruby_in_compile && ruby_parser_stack_on_heap()) {

854 /* If the yacc stack is not on the machine stack,

855 do not collect NODE while parsing */

856 for (i = 0; i < used; i++) {

857 p = heaps[i]; pend = p + heaps_limits[i];

858 while (p < pend) {

859 if (!(p->as.basic.flags & FL_MARK) &&

BUILTIN_TYPE(p) == T_NODE)

860 rb_gc_mark((VALUE)p);

861 p++;

862 }

863 }

864 }

(gc.c)

`NODE` is a object to express a program in the parser. `NODE` is put on the stack prepared by a tool named `yacc` while compiling, but that stack is not always on the machine stack. Concretely speaking, when `ruby_parser_stack_on_heap()` is false, it indicates it is not on the machine stack. In this case, a `NODE` could be accidentally collected in the middle of its creation, thus the objects of type `T_NODE` are unconditionally marked and protected from being collected while compiling (`ruby_in_compile`) .

Finalizer

After it has reached here, all not-marked objects can be freed. However, there’s one thing to do before freeing. In Ruby the freeing of objects can be hooked, and it is necessary to call them. This hook is called “finalizer”.

▼ `gc_sweep()` Middle

869 freelist = 0;

870 final_list = deferred_final_list;

871 deferred_final_list = 0;

872 for (i = 0; i < used; i++) {

873 int n = 0;

874

875 p = heaps[i]; pend = p + heaps_limits[i];

876 while (p < pend) {

877 if (!(p->as.basic.flags & FL_MARK)) {

878 (A) if (p->as.basic.flags) {

879 obj_free((VALUE)p);

880 }

881 (B) if (need_call_final && FL_TEST(p, FL_FINALIZE)) {

882 p->as.free.flags = FL_MARK; /* remains marked */

883 p->as.free.next = final_list;

884 final_list = p;

885 }

886 else {

887 p->as.free.flags = 0;

888 p->as.free.next = freelist;

889 freelist = p;

890 }

891 n++;

892 }

893 (C) else if (RBASIC(p)->flags == FL_MARK) {

894 /* the objects that need to finalize */

895 /* are left untouched */

896 }

897 else {

898 RBASIC(p)->flags &= ~FL_MARK;

899 }

900 p++;

901 }

902 freed += n;

903 }

904 if (freed < FREE_MIN) {

905 add_heap();

906 }

907 during_gc = 0;

(gc.c)

This checks all over the object heap from the edge, and frees the object on which `FL_MARK` flag is not set by using `obj_free()` (A). `obj_free()` frees, for instance, only `char[]` used by String objects or `VALUE[]` used by Array objects, but it does not free the `RVALUE` struct and does not touch `basic.flags` at all. Therefore, if a struct is manipulated after `obj_free()` is called, there’s no worry about going down.

After it frees the objects, it branches based on `FL_FINALIZE` flag (B). If `FL_FINALIZE` is set on an object, since it means at least a finalizer is defined on the object, the object is added to `final_list`. Otherwise, the object is immediately added to `freelist`. When finalizing, `basic.flags` becomes `FL_MARK`. The struct-type flag (such as `T_STRING`) is cleared because of this, and the object can be distinguished from alive objects.

Then, this phase completes by executing the all finalizers. Notice that the hooked objects have already died when calling the finalizers. It means that while executing the finalizers, one cannot use the hooked objects.

▼ `gc_sweep()` the rest

910 if (final_list) {

911 RVALUE *tmp;

912

913 if (rb_prohibit_interrupt || ruby_in_compile) {

914 deferred_final_list = final_list;

915 return;

916 }

917

918 for (p = final_list; p; p = tmp) {

919 tmp = p->as.free.next;

920 run_final((VALUE)p);

921 p->as.free.flags = 0;

922 p->as.free.next = freelist;

923 freelist = p;

924 }

925 }

926 }

(gc.c)

The `for` in the last half is the main finalizing procedure. The `if` in the first half is the case when the execution could not be moved to the Ruby program for various reasons. The objects whose finalization is deferred will be appear in the route (C) of the previous list.

`rb_gc_force_recycle()`

I’ll talk about a little different thing at the end. Until now, the `ruby`‘s garbage collector decides whether or not it collects each object, but there’s also a way that users explicitly let it collect a particular object. It’s `rb_gc_force_recycle()`.

▼ `rb_gc_force_recycle()`

928 void

929 rb_gc_force_recycle(p)

930 VALUE p;

931 {

932 RANY(p)->as.free.flags = 0;

933 RANY(p)->as.free.next = freelist;

934 freelist = RANY(p);

935 }

(gc.c)

Its mechanism is not so special, but I introduced this because you’ll see it several times in Part 2 and Part 3.

Discussions

To free spaces

The space allocated by an individual object, say, `char[]` of `String`, is freed during the sweep phase, but the code to free the `RVALUE` struct itself has not appeared yet. And, the object heap also does not manage the number of structs in use and such. This means that if the `ruby`’s object space is once allocated it would never be freed.

For example, the mailer what I’m creating now temporarily uses the space almost 40M bytes when constructing the threads for 500 mails, but if most of the space becomes unused as the consequence of GC it will keep occupying the 40M bytes. Because my machine is also kind of modern, it does not matter if just the 40M bytes are used. But, if this occurs in a server which keeps running, there’s the possibility of becoming a problem.

However, one also need to consider that `free()` does not always mean the decrease of the amount of memory in use. If it does not return memory to OS, the amount of memory in use of the process never decrease. And, depending on the implementation of `malloc()`, although doing `free()` it often does not cause returning memory to OS.

… I had written so, but just before the deadline of this book, `RVALUE` became to be freed. The attached CD-ROM also contains the edge `ruby`, so please check by `diff`. … what a sad ending.

Generational GC

Mark & Sweep has an weak point, it is “it needs to touch the entire object space at least once”. There’s the possibility that using the idea of Generational GC can make up for the weak point.

The fundamental of Generational GC is the experiential rule that “Most objects are lasting for either very long or very short time”. You may be convinced about this point by thinking for seconds about the programs you write.

Then, thinking based on this rule, one may come up with the idea that “long-lived objects do not need to be marked or swept each and every time”. Once an object is thought that it will be long-lived, it is treated specially and excluded from the GC target. Then, for both marking and sweeping, it can significantly decrease the number of target objects. For example, if half of the objects are long-lived at a particular GC time, the number of the target objects is half.

There’s a problem, though. Generational GC is very difficult to do if objects can’t be moved. It is because the long-lived objects are, as I just wrote, needed to “be treated specially”. Since generational GC decreases the number of the objects dealt with and reduces the cost, if which generation a object belongs to is not clearly categorized, as a consequence it is equivalent to dealing with both generations. Furthermore, the `ruby`’s GC is also a conservative GC, so it also has to be created so that `is_pointer_to_heap()` work. This is particularly difficult.

How to solve this problem is … By the hand of Mr. Kiyama Masato, the implementation of Generational GC for `ruby` has been published. I’ll briefly describe how this patch deals with each problem. And this time, by courtesy of Mr. Kiyama, this Generational GC patch and its paper are contained in attached CD-ROM. (See also `doc/generational-gc.html`)

Then, I shall start the explanation. In order to ease explaining, from now on, the long-lived objects are called as “old-generation objects”, the short-lived objects are called as “new-generation objects”,

First, about the biggest problem which is the special treatment for the old-generation objects. This point is resolved by linking only the new-generation objects into a list named `newlist`. This list is substantialized by increasing `RVALUE`’s elements.

Second, about the way to detect the old-generation objects. It is very simply done by just removing the `newlist` objects which were not garbage collected from the `newlist`. In other words, once an object survives through GC, it will be treated as an old-generation object.

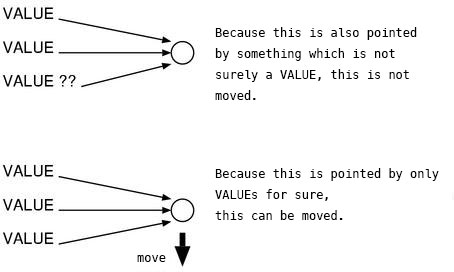

Third, about the way to detect the references from old-generation objects to new-generation objects. In Generational GC, it’s sort of, the old-generation objects keep being in the marked state. However, when there are links from old-generation to new-generation, the new-generation objects will not be marked. (Figure 11)

This is not good, so at the moment when an old-generational object refers to a new-generational object, the new-generational object must be turned into old-generational. The patch modifies the libraries and adds checks to where there’s possibility that this kind of references happens.

This is the outline of its mechanism. It was scheduled that this patch is included `ruby` 1.7, but it has not been included yet. It is said that the reason is its speed, There’s an inference that the cost of the third point “check all references” matters, but the precise cause has not figured out.

Compaction

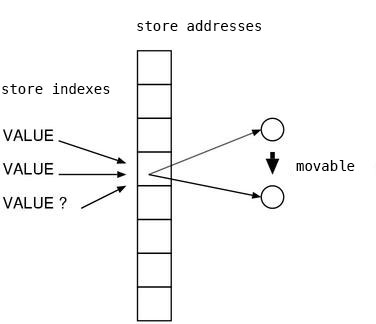

Could the `ruby`’s GC do compaction? Since `VALUE` of `ruby` is a direct pointer to a struct, if the address of the struct are changed because of compaction, it is necessary to change the all `VALUE`s that point to the moved structs.

However, since the `ruby`’s GC is a conservative GC, “the case when it is impossible to determine whether or not it is really a `VALUE`” is possible. Changing the value even though in this situation, if it was not `VALUE` something awful will happen. Compaction and conservative GC are really incompatible.

But, let’s contrive countermeasures in one way or another. The first way is to let `VALUE` be an object ID instead of a pointer. (Figure 12) It means sandwiching a indirect layer between `VALUE` and a struct. In this way, as it’s not necessary to rewrite `VALUE`, structs can be safely moved. But as trade-offs, accessing speed slows down and the compatibility of extension libraries is lost.

Then, the next way is to allow moving the struct only when they are pointed from only the pointers that “is surely `VALUE`” (Figure 13). This method is called Mostly-copying garbage collection. In the ordinary programs, there are not so many objects that `is_pointer_to_heap()` is true, so the probability of being able to move the object structs is quite high.

Moreover and moreover, by enabling to move the struct, the implementation of Generational GC becomes simple at the same time. It seems to be worth to challenge.

`volatile` to protect from GC

I wrote that GC takes care of `VALUE` on the stack, therefore if a `VALUE` is located as a local variable the `VALUE` should certainly be marked. But in reality due to the effects of optimization, it’s possible that the variables disappear. For example, there’s a possibility of disappearing in the following case:

VALUE str;

str = rb_str_new2("...");

printf("%s\n", RSTRING(str)->ptr);

Because this code does not access the `str` itself, some compilers only keeps `str→ptr` in memory and deletes the `str`. If this happened, the `str` would be collected and the process would be down. There’s no choice in this case

volatile VALUE str;

we need to write this way. `volatile` is a reserved word of C, and it has an effect of forbidding optimizations that have to do with this variable. If `volatile` was attached in the code relates to Ruby, you could assume almost certainly that its exists for GC. When I read K & R, I thought “what is the use of this?”, and totally didn’t expect to see the plenty of them in `ruby`.

Considering these aspects, the promise of the conservative GC “users don’t have to care about GC” seems not always true. There was once a discussion that “the Scheme’s GC named KSM does not need `volatile`”, but it seems it could not be applied to `ruby` because its algorithm has a hole.

When to invoke

Inside `gc.c`

When to invoke GC? Inside `gc.c`, there are three places calling `rb_gc()` inside of `gc.c`,

- `ruby_xmalloc()`

- `ruby_xrealloc()`

- `rb_newobj()`

As for `ruby_xmalloc()` and `ruby_xrealloc()`, it is when failing to allocate memory. Doing GC may free memories and it’s possible that a space becomes available again. `rb_newobj()` has a similar situation, it invokes when `freelist` becomes empty.

Inside the interpritor

There’s several places except for `gc.c` where calling `rb_gc()` in the interpretor.

First, in `io.c` and `dir.c`, when it runs out of file descriptors and could not open, it invokes GC. If `IO` objects are garbage collected, it’s possible that the files are closed and file descriptors become available.

In `ruby.c`, `rb_gc()` is sometimes done after loading a file. As I mentioned in the previous Sweep section, it is to compensate for the fact that `NODE` cannot be garbage collected while compiling.

Object Creation

We’ve finished about GC and come to be able to deal with the Ruby objects from its creation to its freeing. So I’d like to describe about object creations here. This is not so related to GC, rather, it is related a little to the discussion about classes in the previous chapter.

Allocation Framework

We’ve created objects many times. For example, in this way:

class C end C.new()

At this time, how does `C.new` create a object?

First, `C.new` is actually `Class#new`. Its actual body is this:

▼ `rb_class_new_instance()`

725 VALUE

726 rb_class_new_instance(argc, argv, klass)

727 int argc;

728 VALUE *argv;

729 VALUE klass;

730 {

731 VALUE obj;

732

733 obj = rb_obj_alloc(klass);

734 rb_obj_call_init(obj, argc, argv);

735

736 return obj;

737 }

(object.c)

`rb_obj_alloc()` calls the `allocate` method against the `klass`. In other words, it calls `C.allocate` in this example currently explained. It is `Class#allocate` by default and its actual body is `rb_class_allocate_instance()`.

▼ `rb_class_allocate_instance()`

708 static VALUE

709 rb_class_allocate_instance(klass)

710 VALUE klass;

711 {

712 if (FL_TEST(klass, FL_SINGLETON)) {

713 rb_raise(rb_eTypeError,

"can't create instance of virtual class");

714 }

715 if (rb_frame_last_func() != alloc) {

716 return rb_obj_alloc(klass);

717 }

718 else {

719 NEWOBJ(obj, struct RObject);

720 OBJSETUP(obj, klass, T_OBJECT);

721 return (VALUE)obj;

722 }

723 }

(object.c)

`rb_newobj()` is a function that returns a `RVALUE` by taking from the `freelist`. `NEWOBJ` with type-casting. The `OBJSETUP()` is a macro to initialize the `struct RBasic` part, you can think that this exists only in order not to forget to set the `FL_TAINT` flag.

The rest is going back to `rb_class_new_instance()`, then it calls `rb_obj_call_init()`. This function calls `initialize` on the just created object, and the initialization completes.

This is summarized as follows:

SomeClass.new = Class#new (rb_class_new_instance)

SomeClass.allocate = Class#allocate (rb_class_allocate_instance)

SomeClass#initialize = Object#initialize (rb_obj_dummy)

I could say that the `allocate` class method is to physically initialize, the `initialize` is to logically initialize. The mechanism like this, in other words the mechanism that an object creation is divided into `allocate` / `initialize` and `new` presides them, is called the “allocation framework”.

Creating User Defined Objects

Next, we’ll examine about the instance creations of the classes defined in extension libraries. As it is called user-defined, its struct is not decided, without telling how to allocate it, `ruby` don’t understand how to create its object. Let’s look at how to tell it.

`Data_Wrap_Struct()`

Whichever it is user-defined or not, its creation mechanism itself can follow the allocation framework. It means that when defining a new `SomeClass` class in C, we overwrite both `SomeClass.allocate` and `SomeClass#initialize`.

Let’s look at the `allocate` side first. Here, it does the physical initialization. What is necessary to allocate? I mentioned that the instance of the user-defined class is a pair of `struct RData` and a user-prepared struct. We’ll assume that the struct is of type `struct my`. In order to create a `VALUE` based on the `struct my`, you can use `Data_Wrap_Struct()`. This is how to use:

struct my *ptr = malloc(sizeof(struct my)); /* arbitrarily allocate in the heap */ VALUE val = Data_Wrap_Struct(data_class, mark_f, free_f, ptr);

`data_class` is the class that `val` belongs to, `ptr` is the pointer to be wrapped. `mark_f` is (the pointer to) the function to mark this struct. However, this does not mark the `ptr` itself and is used when the struct pointed by `ptr` contains `VALUE`. On the other hand, `free_f` is the function to free the `ptr` itself. The argument of the both functions is `ptr`. Going back a little and reading the code to mark may help you to understand things around here in one shot.

Let’s also look at the content of `Data_Wrap_Struct()`.

▼ `Data_Wrap_Struct()`

369 #define Data_Wrap_Struct(klass, mark, free, sval) \

370 rb_data_object_alloc(klass, sval, \

(RUBY_DATA_FUNC)mark, \

(RUBY_DATA_FUNC)free)

365 typedef void (*RUBY_DATA_FUNC) _((void*));

(ruby.h)

Most of it is delegated to `rb_object_alloc()`.

▼ `rb_data_object_alloc()`

310 VALUE

311 rb_data_object_alloc(klass, datap, dmark, dfree)

312 VALUE klass;

313 void *datap;

314 RUBY_DATA_FUNC dmark;

315 RUBY_DATA_FUNC dfree;

316 {

317 NEWOBJ(data, struct RData);

318 OBJSETUP(data, klass, T_DATA);

319 data->data = datap;

320 data->dfree = dfree;

321 data->dmark = dmark;

322

323 return (VALUE)data;

324 }

(gc.c)

This is not complicated. As the same as the ordinary objects, it prepares a `RVALUE` by using `NEWOBJ`, and sets the members.

Here, let’s go back to `allocate`. We’ve succeeded to create a `VALUE` by now, so the rest is putting it in an arbitrary function and defining the function on a class by `rb_define_singleton_method()`.

`Data_Get_Struct()`

The next thing is `initialize`. Not only for `initialize`, the methods need a way to pull out the `struct my*` from the previously created `VALUE`. In order to do it, you can use the `Data_Get_Struct()` macro.

▼ `Data_Get_Struct()`

378 #define Data_Get_Struct(obj,type,sval) do {\

379 Check_Type(obj, T_DATA); \

380 sval = (type*)DATA_PTR(obj);\

381 } while (0)

360 #define DATA_PTR(dta) (RDATA(dta)->data)

(ruby.h)

As you see, it just takes the pointer (to `struct my`) from a member of `RData`. This is simple. `Check_Type()` just checks the struct type.

The Issues of the Allocation Framework

So, I’ve explained innocently until now, but actually the current allocation framework has a fatal issue. I just described that the object created with `allocate` appears to the `initialize` or the other methods, but if the passed object that was created with `allocate` is not of the same class, it must be a very serious problem. For example, if the object created with the default `Objct.allocate` (`Class#allocate`) is passed to the method of `String`, this cause a serious problem. That is because even though the methods of `String` are written based on the assumption that a struct of type `struct RString` is given, the given object is actually a `struct RObject`. In order to avoid such situation, the object created with `C.allocate` must be passed only to the methods of `C` or its subclasses.

Of course, this is always true when things are ordinarily done. As `C.allocate` creates the instance of the class `C`, it is not passed to the methods of the other classes. As an exception, it is possible that it is passed to the method of `Object`, but the methods of `Object` does not depend on the struct type.

However, what if it is not ordinarily done? Since `C.allocate` is exposed at the Ruby level, though I’ve not described about them yet, by making use of `alias` or `super` or something, the definition of `allocate` can be moved to another class. In this way, you can create an object whose class is `String` but whose actual struct type is `struct RObject`. It means that you can freely let `ruby` down from the Ruby level. This is a problem.

The source of the issue is that `allocate` is exposed to the Ruby level as a method. Conversely speaking, a solution is to define the content of `allocate` on the class by using a way that is anything but a method. So,

rb_define_allocator(rb_cMy, my_allocate);

an alternative like this is currently in discussion.