Ruby Hacking Guide

Translated by Vincent ISAMBART

Chapter 2: Objects

Structure of Ruby objects

Guideline

From this chapter, we will begin actually exploring the `ruby` source code. First, as declared at the beginning of this book, we’ll start with the object structure.

What are the necessary conditions for objects to be objects? There could be many ways to explain about object itself, but there are only three conditions that are truly indispensable.

- The ability to differentiate itself from other objects (an identity)

- The ability to respond to messages (methods)

- The ability to store internal state (instance variables)

In this chapter, we are going to confirm these three features one by one.

The target file is mainly `ruby.h`, but we will also briefly look at other files such as `object.c`, `class.c` or `variable.c`.

`VALUE` and object struct

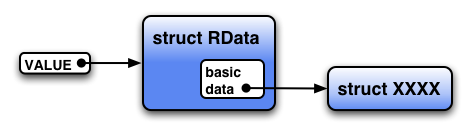

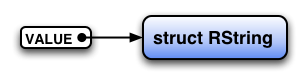

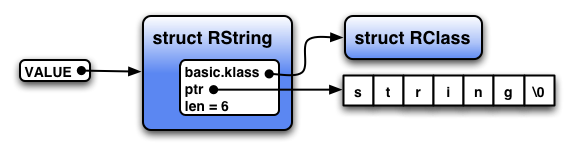

In `ruby`, the body of an object is expressed by a struct and always handled via a pointer. A different struct type is used for each class, but the pointer type will always be `VALUE` (figure 1).

Here is the definition of `VALUE`:

▼ `VALUE`

71 typedef unsigned long VALUE; (ruby.h)

In practice, when using a `VALUE`, we cast it to the pointer to each object struct. Therefore if an `unsigned long` and a pointer have a different size, `ruby` will not work well. Strictly speaking, it will not work if there’s a pointer type that is bigger than `sizeof(unsigned long)`. Fortunately, systems which could not meet this requirement is unlikely recently, but some time ago it seems there were quite a few of them.

The structs, on the other hand, have several variations, a different struct is used based on the class of the object.

| `struct RObject` | all things for which none of the following applies |

| `struct RClass` | class object |

| `struct RFloat` | small numbers |

| `struct RString` | string |

| `struct RArray` | array |

| `struct RRegexp` | regular expression |

| `struct RHash` | hash table |

| `struct RFile` | `IO`, `File`, `Socket`, etc… |

| `struct RData` | all the classes defined at C level, except the ones mentioned above |

| `struct RStruct` | Ruby’s `Struct` class |

| `struct RBignum` | big integers |

For example, for an string object, `struct RString` is used, so we will have something like the following.

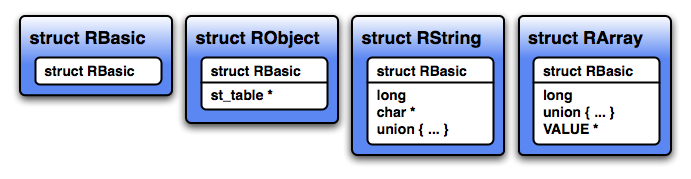

Let’s look at the definition of a few object structs.

▼ Examples of object struct

/* struct for ordinary objects */

295 struct RObject {

296 struct RBasic basic;

297 struct st_table *iv_tbl;

298 };

/* struct for strings (instance of String) */

314 struct RString {

315 struct RBasic basic;

316 long len;

317 char *ptr;

318 union {

319 long capa;

320 VALUE shared;

321 } aux;

322 };

/* struct for arrays (instance of Array) */

324 struct RArray {

325 struct RBasic basic;

326 long len;

327 union {

328 long capa;

329 VALUE shared;

330 } aux;

331 VALUE *ptr;

332 };

(ruby.h)

Before looking at every one of them in detail, let’s begin with something more general.

First, as `VALUE` is defined as `unsigned long`, it must be cast before being used when it is used as a pointer. That’s why `Rxxxx()` macros have been made for each object struct. For example, for `struct RString` there is `RSTRING`, etc… These macros are used like this:

VALUE str = ....; VALUE arr = ....; RSTRING(str)->len; /* ((struct RString*)str)->len */ RARRAY(arr)->len; /* ((struct RArray*)arr)->len */

Another important point to mention is that all object structs start with a member `basic` of type `struct RBasic`. As a result, if you cast this `VALUE` to `struct RBasic*`, you will be able to access the content of `basic`, regardless of the type of struct pointed to by `VALUE`.

Because it is purposefully designed this way, `struct RBasic` must contain very important information for Ruby objects. Here is the definition for `struct RBasic`:

▼ `struct RBasic`

290 struct RBasic {

291 unsigned long flags;

292 VALUE klass;

293 };

(ruby.h)

`flags` are multipurpose flags, mostly used to register the struct type (for instance `struct RObject`). The type flags are named `T_xxxx`, and can be obtained from a `VALUE` using the macro `TYPE()`. Here is an example:

VALUE str; str = rb_str_new(); /* creates a Ruby string (its struct is RString) */ TYPE(str); /* the return value is T_STRING */

The all flags are named as `T_xxxx`, like `T_STRING` for `struct RString` and `T_ARRAY` for `struct RArray`. They are very straightforwardly corresponded to the type names.

The other member of `struct RBasic`, `klass`, contains the class this object belongs to. As the `klass` member is of type `VALUE`, what is stored is (a pointer to) a Ruby object. In short, it is a class object.

The relation between an object and its class will be detailed in the “Methods” section of this chapter.

By the way, this member is named `klass` so as not to conflict with the reserved word `class` when the file is processed by a C++ compiler.

About struct types

I said that the type of struct is stored in the `flags` member of `struct Basic`. But why do we have to store the type of struct? It’s to be able to handle all different types of struct via `VALUE`. If you cast a pointer to a struct to `VALUE`, as the type information does not remain, the compiler won’t be able to help. Therefore we have to manage the type ourselves. That’s the consequence of being able to handle all the struct types in a unified way.

OK, but the used struct is defined by the class so why are the struct type and class are stored separately? Being able to find the struct type from the class should be enough. There are two reasons for not doing this.

The first one is (I’m sorry for contradicting what I said before), in fact there are structs that do not have a `struct RBasic` (i.e. they have no `klass` member). For example `struct RNode` that will appear in the second part of the book. However, `flags` is guaranteed to be in the beginning members even in special structs like this. So if you put the type of struct in `flags`, all the object structs can be differentiated in one unified way.

The second reason is that there is no one-to-one correspondence between class and struct. For example, all the instances of classes defined at the Ruby level use `struct RObject`, so finding a struct from a class would require to keep the correspondence between each class and struct. That’s why it’s easier and faster to put the information about the type in the struct.

The use of `basic.flags`

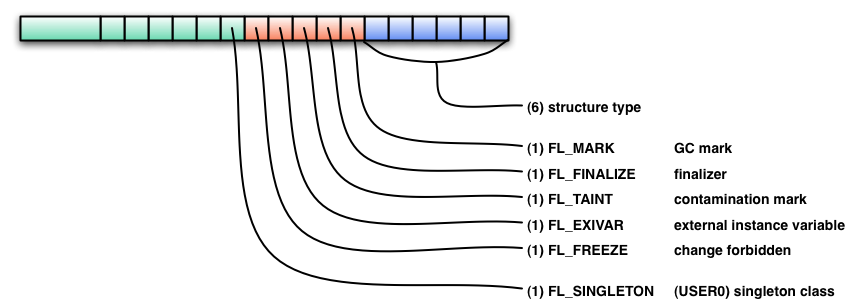

Regarding the use of `basic.flags`, because I feel bad to say it is the struct type “and such”, I’ll illustrate it entirely here. (Figure 5) There is no need to understand everything right away, because this is prepared for the time when you will be wondering about it later.

When looking at the diagram, it looks like that 21 bits are not used on 32 bit machines. On these additional bits, the flags `FL_USER0` to `FL_USER8` are defined, and are used for a different purpose for each struct. In the diagram I also put `FL_USER0` (`FL_SINGLETON`) as an example.

Objects embedded in `VALUE`

As I said, `VALUE` is an `unsigned long`. As `VALUE` is a pointer, it may look like `void*` would also be all right, but there is a reason for not doing this. In fact, `VALUE` can also not be a pointer. The 6 cases for which `VALUE` is not a pointer are the following:

- small integers

- symbols

- `true`

- `false`

- `nil`

- `Qundef`

I’ll explain them one by one.

Small integers

All data are objects in Ruby, thus integers are also objects. But since there are so many kind of integer objects, if each of them is expressed as a struct, it would risk slowing down execution significantly. For example, when incrementing from 0 to 50000, we would hesitate to create 50000 objects for only that purpose.

That’s why in `ruby`, integers that are small to some extent are treated specially and embedded directly into `VALUE`. “Small” means signed integers that can be held in `sizeof(VALUE)*8-1` bits. In other words, on 32 bits machines, the integers have 1 bit for the sign, and 30 bits for the integer part. Integers in this range will belong to the `Fixnum` class and the other integers will belong to the `Bignum` class.

Let’s see in practice the `INT2FIX()` macro that converts from a C `int` to a `Fixnum`, and confirm that `Fixnum` are directly embedded in `VALUE`.

▼ `INT2FIX`

123 #define INT2FIX(i) ((VALUE)(((long)(i))<<1 | FIXNUM_FLAG)) 122 #define FIXNUM_FLAG 0x01 (ruby.h)

In brief, shift 1 bit to the left, and bitwise or it with 1.

| ` 110100001000` | before conversion |

| `1101000010001` | after conversion |

That means that `Fixnum` as `VALUE` will always be an odd number. On the other hand, as Ruby object structs are allocated with `malloc()`, they are generally arranged on addresses multiple of 4. So they do not overlap with the values of `Fixnum` as `VALUE`.

Also, to convert `int` or `long` to `VALUE`, we can use macros like `INT2NUM`. Any conversion macro `XXXX2XXXX` with a name containing `NUM` can manage both `Fixnum` and `Bignum`. For example if `INT2NUM` will convert both `Fixnum` and `Bignum` to `int`. If the number can’t fit in an `int`, an exception will be raised, so there is no need to check the value range.

Symbols

What are symbols?

As this question is quite troublesome to answer, let’s start with the reasons why symbols were necessary. In the first place, there’s a type named `ID` used inside `ruby`. Here it is.

▼ `ID`

72 typedef unsigned long ID; (ruby.h)

This `ID` is a number having a one-to-one association with a string. However, it’s not possible to have an association between all strings in this world and numerical values. It is limited to the one to one relationships inside one `ruby` process. I’ll speak of the method to find an `ID` in the next chapter “Names and name tables.”

In language processor, there are a lot of names to handle. Method names or variable names, constant names, file names, class names… It’s troublesome to handle all of them as strings (`char*`), because of memory management and memory management and memory management… Also, lots of comparisons would certainly be necessary, but comparing strings character by character will slow down the execution. That’s why strings are not handled directly, something will be associated and used instead. And generally that “something” will be integers, as they are the simplest to handle.

These `ID` are found as symbols in the Ruby world. Up to `ruby 1.4`, the values of `ID` converted to `Fixnum` were used as symbols. Even today these values can be obtained using `Symbol#to_i`. However, as real use results came piling up, it was understood that making `Fixnum` and `Symbol` the same was not a good idea, so since 1.6 an independent class `Symbol` has been created.

`Symbol` objects are used a lot, especially as keys for hash tables. That’s why `Symbol`, like `Fixnum`, was made embedded in `VALUE`. Let’s look at the `ID2SYM()` macro converting `ID` to `Symbol` object.

▼ `ID2SYM`

158 #define SYMBOL_FLAG 0x0e 160 #define ID2SYM(x) ((VALUE)(((long)(x))<<8|SYMBOL_FLAG)) (ruby.h)

When shifting 8 bits left, `x` becomes a multiple of 256, that means a multiple of 4. Then after with a bitwise or (in this case it’s the same as adding) with `0×0e` (14 in decimal), the `VALUE` expressing the symbol is not a multiple of 4. Or even an odd number. So it does not overlap the range of any other `VALUE`. Quite a clever trick.

Finally, let’s see the reverse conversion of `ID2SYM`.

▼ `SYM2ID()`

161 #define SYM2ID(x) RSHIFT((long)x,8) (ruby.h)

`RSHIFT` is a bit shift to the right. As right shift may keep or not the sign depending of the platform, it became a macro.

`true false nil`

These three are Ruby special objects. `true` and `false` represent the boolean values. `nil` is an object used to denote that there is no object. Their values at the C level are defined like this:

▼ `true false nil`

164 #define Qfalse 0 /* Ruby's false */ 165 #define Qtrue 2 /* Ruby's true */ 166 #define Qnil 4 /* Ruby's nil */ (ruby.h)

This time it’s even numbers, but as 0 or 2 can’t be used by pointers, they can’t overlap with other `VALUE`. It’s because usually the first block of virtual memory is not allocated, to make the programs dereferencing a `NULL` pointer crash.

And as `Qfalse` is 0, it can also be used as false at C level. In practice, in `ruby`, when a function returns a boolean value, it’s often made to return an `int` or `VALUE`, and returns `Qtrue`/`Qfalse`.

For `Qnil`, there is a macro dedicated to check if a `VALUE` is `Qnil` or not, `NIL_P()`.

▼ `NIL_P()`

170 #define NIL_P(v) ((VALUE)(v) == Qnil) (ruby.h)

The name ending with `p` is a notation coming from Lisp denoting that it is a function returning a boolean value. In other words, `NIL_P` means “is the argument `nil`?” It seems the “`p`” character comes from “predicate.” This naming rule is used at many different places in `ruby`.

Also, in Ruby, `false` and `nil` are false (in conditional statements) and all the other objects are true. However, in C, `nil` (`Qnil`) is true. That’s why there’s the `RTEST()` macro to do Ruby-style test in C.

▼ `RTEST()`

169 #define RTEST(v) (((VALUE)(v) & ~Qnil) != 0) (ruby.h)

As in `Qnil` only the third lower bit is 1, in `~Qnil` only the third lower bit is 0. Then only `Qfalse` and `Qnil` become 0 with a bitwise and.

`!=0` has been added to be certain to only have 0 or 1, to satisfy the requirements of the glib library that only wants 0 or 1 ([ruby-dev:11049]).

By the way, what is the ‘`Q`’ of `Qnil`? ‘R’ I would have understood but why ‘`Q`’? When I asked, the answer was “Because it’s like that in Emacs.” I did not have the fun answer I was expecting…

`Qundef`

▼ `Qundef`

167 #define Qundef 6 /* undefined value for placeholder */ (ruby.h)

This value is used to express an undefined value in the interpreter. It can’t (must not) be found at all at the Ruby level.

Methods

I already brought up the three important points of a Ruby object: having an identity, being able to call a method, and keeping data for each instance. In this section, I’ll explain in a simple way the structure linking objects and methods.

`struct RClass`

In Ruby, classes exist as objects during the execution. Of course. So there must be a struct for class objects. That struct is `struct RClass`. Its struct type flag is `T_CLASS`.

As classes and modules are very similar, there is no need to differentiate their content. That’s why modules also use the `struct RClass` struct, and are differentiated by the `T_MODULE` struct flag.

▼ `struct RClass`

300 struct RClass {

301 struct RBasic basic;

302 struct st_table *iv_tbl;

303 struct st_table *m_tbl;

304 VALUE super;

305 };

(ruby.h)

First, let’s focus on the `m_tbl` (Method TaBLe) member. `struct st_table` is an hashtable used everywhere in `ruby`. Its details will be explained in the next chapter “Names and name tables”, but basically, it is a table mapping names to objects. In the case of `m_tbl`, it keeps the correspondence between the name (`ID`) of the methods possessed by this class and the methods entity itself. As for the structure of the method entity, it will be explained in Part 2 and Part 3.

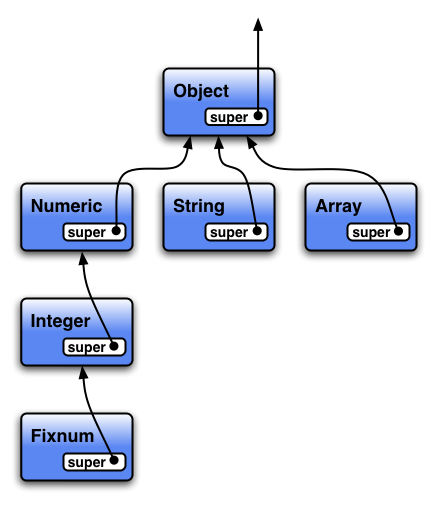

The fourth member `super` keeps, like its name suggests, the superclass. As it’s a `VALUE`, it’s (a pointer to) the class object of the superclass. In Ruby there is only one class that has no superclass (the root class): `Object`.

However I already said that all `Object` methods are defined in the `Kernel` module, `Object` just includes it. As modules are functionally similar to multiple inheritance, it may seem having just `super` is problematic, but in `ruby` some clever conversions are made to make it look like single inheritance. The details of this process will be explained in the fourth chapter “Classes and modules.”

Because of this conversion, `super` of the struct of `Object` points to `struct RClass` which is the entity of `Kernel` object and the `super` of Kernel is `NULL`. So to put it conversely, if `super` is `NULL`, its `RClass` is the entity of `Kernel` (figure 6).

Methods search

With classes structured like this, you can easily imagine the method call process. The `m_tbl` of the object’s class is searched, and if the method was not found, the `m_tbl` of `super` is searched, and so on. If there is no more `super`, that is to say the method was not found even in `Object`, then it must not be defined.

The sequential search process in `m_tbl` is done by `search_method()`.

▼ `search_method()`

256 static NODE*

257 search_method(klass, id, origin)

258 VALUE klass, *origin;

259 ID id;

260 {

261 NODE *body;

262

263 if (!klass) return 0;

264 while (!st_lookup(RCLASS(klass)->m_tbl, id, &body)) {

265 klass = RCLASS(klass)->super;

266 if (!klass) return 0;

267 }

268

269 if (origin) *origin = klass;

270 return body;

271 }

(eval.c)

This function searches the method named `id` in the class object `klass`.

`RCLASS` is the macro doing:

((struct RClass*)(value))

`st_lookup()` is a function that searches in `st_table` the value corresponding to a key. If the value is found, the function returns true and puts the found value at the address given in third parameter (`&body`).

Nevertheless, doing this search each time whatever the circumstances would be too slow. That’s why in reality, once called, a method is cached. So starting from the second time it will be found without following `super` one by one. This cache and its search will be seen in the 15th chapter “Methods.”

Instance variables

In this section, I will explain the implementation of the third essential condition, instance variables.

`rb_ivar_set()`

Instance variable is the mechanism that allows each object to hold its specific data. Since it is specific to each object, it seems good to store it in each object itself (i.e. in its object struct), but is it really so? Let’s look at the function `rb_ivar_set()`, which assigns an object to an instance variable.

▼ `rb_ivar_set()`

/* assign val to the id instance variable of obj */

984 VALUE

985 rb_ivar_set(obj, id, val)

986 VALUE obj;

987 ID id;

988 VALUE val;

989 {

990 if (!OBJ_TAINTED(obj) && rb_safe_level() >= 4)

991 rb_raise(rb_eSecurityError,

"Insecure: can't modify instance variable");

992 if (OBJ_FROZEN(obj)) rb_error_frozen("object");

993 switch (TYPE(obj)) {

994 case T_OBJECT:

995 case T_CLASS:

996 case T_MODULE:

997 if (!ROBJECT(obj)->iv_tbl)

ROBJECT(obj)->iv_tbl = st_init_numtable();

998 st_insert(ROBJECT(obj)->iv_tbl, id, val);

999 break;

1000 default:

1001 generic_ivar_set(obj, id, val);

1002 break;

1003 }

1004 return val;

1005 }

(variable.c)

`rb_raise()` and `rb_error_frozen()` are both error checks. This can always be said hereafter: Error checks are necessary in reality, but it’s not the main part of the process. Therefore, we should wholly ignore them at first read.

After removing the error handling, only the `switch` remains, but

switch (TYPE(obj)) {

case T_aaaa:

case T_bbbb:

...

}

this form is an idiom of `ruby`. `TYPE. In other words as the type flag is an integer constant, we can branch depending on it with a `switch`. `Fixnum` or `Symbol` do not have structs, but inside `TYPE()` a special treatment is done to properly return `T_FIXNUM` and `T_SYMBOL`, so there’s no need to worry.

Well, let’s go back to `rb_ivar_set()`. It seems only the treatments of `T_OBJECT`, `T_CLASS` and `T_MODULE` are different. These 3 have been chosen on the basis that their second member is `iv_tbl`. Let’s confirm it in practice.

▼ Structs whose second member is `iv_tbl`

/* TYPE(val) == T_OBJECT */

295 struct RObject {

296 struct RBasic basic;

297 struct st_table *iv_tbl;

298 };

/* TYPE(val) == T_CLASS or T_MODULE */

300 struct RClass {

301 struct RBasic basic;

302 struct st_table *iv_tbl;

303 struct st_table *m_tbl;

304 VALUE super;

305 };

(ruby.h)

`iv_tbl` is the Instance Variable TaBLe. It records the correspondences between the instance variable names and their values.

In `rb_ivar_set()`, let’s look again the code for the structs having `iv_tbl`.

if (!ROBJECT(obj)->iv_tbl)

ROBJECT(obj)->iv_tbl = st_init_numtable();

st_insert(ROBJECT(obj)->iv_tbl, id, val);

break;

`ROBJECT()` is a macro that casts a `VALUE` into a `struct RObject*`. It’s possible that what `obj` points to is actually a struct RClass, but when accessing only the second member, no problem will occur.

`st_init_numtable()` is a function creating a new `st_table`. `st_insert()` is a function doing associations in a `st_table`.

In conclusion, this code does the following: if `iv_tbl` does not exist, it creates it, then stores the [variable name → object] association.

There’s one thing to be careful about. As `struct RClass` is the struct of a class object, its instance variable table is for the class object itself. In Ruby programs, it corresponds to something like the following:

class C @ivar = "content" end

`generic_ivar_set()`

What happens when assigning to an instance variable of an object whose struct is not one of `T_OBJECT T_MODULE T_CLASS`?

▼ `rb_ivar_set()` in the case there is no `iv_tbl`

1000 default: 1001 generic_ivar_set(obj, id, val); 1002 break; (variable.c)

This is delegated to `generic_ivar_set()`. Before looking at this function, let’s first explain its general idea.

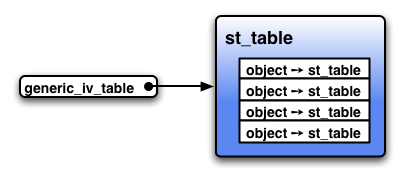

Structs that are not `T_OBJECT`, `T_MODULE` or `T_CLASS` do not have an `iv_tbl` member (the reason why they do not have it will be explained later). However, even if it does not have the member, if there’s another method linking an instance to a `struct st_table`, it would be able to have instance variables. In `ruby`, these associations are solved by using a global `st_table`, `generic_iv_table` (figure 7).

Let’s see this in practice.

▼ `generic_ivar_set()`

801 static st_table *generic_iv_tbl;

830 static void

831 generic_ivar_set(obj, id, val)

832 VALUE obj;

833 ID id;

834 VALUE val;

835 {

836 st_table *tbl;

837

/* for the time being you can ignore this */

838 if (rb_special_const_p(obj)) {

839 special_generic_ivar = 1;

840 }

/* initialize generic_iv_tbl if it does not exist */

841 if (!generic_iv_tbl) {

842 generic_iv_tbl = st_init_numtable();

843 }

844

/* the process itself */

845 if (!st_lookup(generic_iv_tbl, obj, &tbl)) {

846 FL_SET(obj, FL_EXIVAR);

847 tbl = st_init_numtable();

848 st_add_direct(generic_iv_tbl, obj, tbl);

849 st_add_direct(tbl, id, val);

850 return;

851 }

852 st_insert(tbl, id, val);

853 }

(variable.c)

`rb_special_const_p()` is true when its parameter is not a pointer. However, as this `if` part requires knowledge of the garbage collector, we’ll skip it for now. I’d like you to check it again after reading the chapter 5 “Garbage collection.”

`st_init_numtable()` already appeared some time ago. It creates a new hash table.

`st_lookup()` searches a value corresponding to a key. In this case it searches for what’s attached to `obj`. If an attached value can be found, the whole function returns true and stores the value at the address (`&tbl`) given as third parameter. In short, `!st_lookup(…)` can be read “if a value can’t be found.”

`st_insert()` was also already explained. It stores a new association in a table.

`st_add_direct()` is similar to `st_insert()`, but it does not check if the key was already stored before adding an association. It means, in the case of `st_add_direct()`, if a key already registered is being used, two associations linked to this same key will be stored. We can use `st_add_direct()` only when the check for existence has already been done, or when a new table has just been created. And this code would meet these requirements.

`FL_SET(obj, FL_EXIVAR)` is the macro that sets the `FL_EXIVAR` flag in the `basic.flags` of `obj`. The `basic.flags` flags are all named `FL_xxxx` and can be set using `FL_SET()`. These flags can be unset with `FL_UNSET()`. The `EXIVAR` from `FL_EXIVAR` seems to be the abbreviation of EXternal Instance VARiable.

This flag is set to speed up the reading of instance variables. If `FL_EXIVAR` is not set, even without searching in `generic_iv_tbl`, we can see the object does not have any instance variables. And of course a bit check is way faster than searching a `struct st_table`.

Gaps in structs

Now you understood the way to store the instance variables, but why are there structs without `iv_tbl`? Why is there no `iv_tbl` in `struct RString` or `struct RArray`? Couldn’t `iv_tbl` be part of `RBasic`?

To tell the conclusion first, we can do such thing, but should not. As a matter of fact, this problem is deeply linked to the way `ruby` manages objects.

In `ruby`, the memory used for string data (`char[]`) and such is directly allocated using `malloc()`. However, the object structs are handled in a particular way. `ruby` allocates them by clusters, and then distribute them from these clusters. And in this way, if the types (or rather their sizes) were diverse, it’s hard to manage, thus `RVALUE`, which is the union of the all structs, is defined and the array of the unions is managed.

The size of a union is the same as the size of the biggest member, so for instance, if one of the structs is big, a lot of space would be wasted. Therefore, it’s preferable that each struct size is as similar as possible.

The most used struct might be usually `struct RString`. After that, depending on each program, there comes `struct RArray` (array), `RHash` (hash), `RObject` (user defined object), etc. However, this `struct RObject` only uses the space of `struct RBasic` + 1 pointer. On the other hand, `struct RString`, `RArray` and `RHash` take the space of `struct RBasic` + 3 pointers. In other words, when the number of `struct RObject` is being increased, the memory space of the two pointers for each object are wasted. Furthermore, if the size of `RString` was as much as 4 pointers, `Robject` would use less than the half size of the union, and this is too wasteful.

So the benefit of `iv_tbl` is more or less saving memory and speeding up. Furthermore we do not know if it is used often or not. In fact, `generic_iv_tbl` was not introduced before `ruby` 1.2, so it was not possible to use instance variables in `String` or `Array` at that time. Nevertheless, it was not much of a problem. Making large amounts of memory useless just for such functionality looks stupid.

If you take all this into consideration, you can conclude that increasing the size of object structs for `iv_tbl` does not do any good.

`rb_ivar_get()`

We saw the `rb_ivar_set()` function that sets variables, so let’s see quickly how to get them.

▼ `rb_ivar_get()`

960 VALUE

961 rb_ivar_get(obj, id)

962 VALUE obj;

963 ID id;

964 {

965 VALUE val;

966

967 switch (TYPE(obj)) {

/* (A) */

968 case T_OBJECT:

969 case T_CLASS:

970 case T_MODULE:

971 if (ROBJECT(obj)->iv_tbl &&

st_lookup(ROBJECT(obj)->iv_tbl, id, &val))

972 return val;

973 break;

/* (B) */

974 default:

975 if (FL_TEST(obj, FL_EXIVAR) || rb_special_const_p(obj))

976 return generic_ivar_get(obj, id);

977 break;

978 }

/* (C) */

979 rb_warning("instance variable %s not initialized", rb_id2name(id));

980

981 return Qnil;

982 }

(variable.c)

The structure is completely the same.

(A) For `struct RObject` or `RClass`, we search the variable in `iv_tbl`. As `iv_tbl` can also be `NULL`, we must check it before using it. Then if `st_lookup()` finds the relation, it returns true, so the whole `if` can be read as “If the instance variable has been set, return its value.”

(C) If no correspondence could be found, in other words if we read an instance variable that has not been set, we first leave the `if` then the `switch`. `rb_warning()` will then issue a warning and `nil` will be returned. That’s because you can read instance variables that have not been set in Ruby.

(B) On the other hand, if the struct is neither `struct RObject` nor `RClass`, the instance variable table is searched in `generic_iv_tbl`. What `generic_ivar_get()` does can be easily guessed, so I won’t explain it. I’d rather want you to focus on the condition of the `if` statement.

I already told you that the `FL_EXIRVAR` flag is set to the object on which `generic_ivar_set()` is used. Here, that flag is utilized to make the check faster.

And what is `rb_special_const_p()`? This function returns true when its parameter `obj` does not point to a struct. As no struct means no `basic.flags`, no flag can be set in the first place. Thus `FL_xxxx()` is designed to always return false for such object. Hence, objects that are `rb_special_const_p()` should be treated specially here.

Object Structs

In this section, about the important ones among object structs, we’ll briefly see their concrete appearances and how to deal with them.

`struct RString`

`struct RString` is the struct for the instances of the `String` class and its subclasses.

▼ `struct RString`

314 struct RString {

315 struct RBasic basic;

316 long len;

317 char *ptr;

318 union {

319 long capa;

320 VALUE shared;

321 } aux;

322 };

(ruby.h)

`ptr` is a pointer to the string, and `len` the length of that string. Very straightforward.

Rather than a string, Ruby’s string is more a byte array, and can contain any byte including `NUL`. So when thinking at the Ruby level, ending the string with `NUL` does not mean anything. But as C functions require `NUL`, for convenience the ending `NUL` is there. However, its size is not included in `len`.

When dealing with a string from the interpreter or an extension library, you can access `ptr` and `len` by writing `RSTRING→ptr` or `RSTRING→len`, and it is allowed. But there are some points to pay attention to.

- you have to check if `str` really points to a `struct RString` by yourself beforehand

- you can read the members, but you must not modify them

- you can’t store `RSTRING→ptr` in something like a local variable and use it later

Why is that? First, there is an important software engineering principle: Don’t arbitrarily tamper with someone’s data. When there are interface functions, we should use them. However, there are also concrete reasons in `ruby`‘s design why you should not refer to or store a pointer, and that’s related to the fourth member `aux`. However, to explain properly how to use `aux`, we have to explain first a little more of Ruby’s strings’ characteristics.

Ruby’s strings can be modified (are mutable). By mutable I mean after the following code:

s = "str" # create a string and assign it to s

s.concat("ing") # append "ing" to this string object

p(s) # show "string"

the content of the object pointed by `s` will become “`string`”. It’s different from Java or Python string objects. Java’s `StringBuffer` is closer.

And what’s the relation? First, mutable means the length (`len`) of the string can change. We have to increase or decrease the allocated memory size each time the length changes. We can of course use `realloc()` for that, but generally `malloc()` and `realloc()` are heavy operations. Having to `realloc()` each time the string changes is a huge burden.

That’s why the memory pointed by `ptr` has been allocated with a size a little bigger than `len`. Because of that, if the added part can fit into the remaining memory, it’s taken care of without calling `realloc()`, so it’s faster. The struct member `aux.capa` contains the length including this additional memory.

So what is this other `aux.shared`? It’s to speed up the creation of literal strings. Have a look at the following Ruby program.

while true do # repeat indefinitely

a = "str" # create a string with "str" as content and assign it to a

a.concat("ing") # append "ing" to the object pointed by a

p(a) # show "string"

end

Whatever the number of times you repeat the loop, the fourth line’s `p` has to show `“string”`. And to do so, the expression `“str”` must every time create an object that holds a distinct `char[]`. But there must be also the high possibility that strings are not modified at all, and a lot of useless copies of `char[]` would be created in such situation. If possible, we’d like to share one common `char[]`.

The trick to share is `aux.shared`. Every string object created with a literal uses one shared `char[]`. And after a change occurs, the object-specific memory is allocated. When using a shared `char[]`, the flag `ELTS_SHARED` is set in the object struct’s `basic.flags`, and `aux.shared` contains the original object. `ELTS` seems to be the abbreviation of `ELemenTS`.

Then, let’s return to our talk about `RSTRING→ptr`. Though referring to a pointer is OK, you must not assign to it. This is first because the value of `len` or `capa` will no longer agree with the actual body, and also because when modifying strings created as litterals, `aux.shared` has to be separated.

Before ending this section, I’ll write some examples of dealing with `RString`. I’d like you to regard `str` as a `VALUE` that points to `RString` when reading this.

RSTRING(str)->len; /* length */

RSTRING(str)->ptr[0]; /* first character */

str = rb_str_new("content", 7); /* create a string with "content" as its content

the second parameter is the length */

str = rb_str_new2("content"); /* create a string with "content" as its content

its length is calculated with strlen() */

rb_str_cat2(str, "end"); /* Concatenate a C string to a Ruby string */

`struct RArray`

`struct RArray` is the struct for the instances of Ruby’s array class `Array`.

▼ `struct RArray`

324 struct RArray {

325 struct RBasic basic;

326 long len;

327 union {

328 long capa;

329 VALUE shared;

330 } aux;

331 VALUE *ptr;

332 };

(ruby.h)

Except for the type of `ptr`, this structure is almost the same as `struct RString`. `ptr` points to the content of the array, and `len` is its length. `aux` is exactly the same as in `struct RString`. `aux.capa` is the “real” length of the memory pointed by `ptr`, and if `ptr` is shared, `aux.shared` stores the shared original array object.

From this structure, it’s clear that Ruby’s `Array` is an array and not a list. So when the number of elements changes in a big way, a `realloc()` must be done, and if an element must be inserted at an other place than the end, a `memmove()` will occur. But even if it does it, it’s moving so fast that we don’t notice about that. Recent machines are really impressive.

And the way to access to its members is similar to the way of `RString`. With `RARRAY→ptr` and `RARRAY→len`, you can refer to the members, and it is allowed, but you must not assign to them, etc. We’ll only look at simple examples:

/* manage an array from C */ VALUE ary; ary = rb_ary_new(); /* create an empty array */ rb_ary_push(ary, INT2FIX(9)); /* push a Ruby 9 */ RARRAY(ary)->ptr[0]; /* look what's at index 0 */ rb_p(RARRAY(ary)->ptr[0]); /* do p on ary[0] (the result is 9) */ # manage an array from Ruby ary = [] # create an empty array ary.push(9) # push 9 ary[0] # look what's at index 0 p(ary[0]) # do p on ary[0] (the result is 9)

`struct RRegexp`

It’s the struct for the instances of the regular expression class `Regexp`.

▼ `struct RRegexp`

334 struct RRegexp {

335 struct RBasic basic;

336 struct re_pattern_buffer *ptr;

337 long len;

338 char *str;

339 };

(ruby.h)

`ptr` is the compiled regular expression. `str` is the string before compilation (the source code of the regular expression), and `len` is this string’s length.

As any code to handle `Regexp` objects doesn’t appear in this book, we won’t see how to use it. Even if you use it in extension libraries, as long as you do not want to use it a very particular way, the interface functions are enough.

`struct RHash`

`struct RHash` is the struct for `Hash` object, which is Ruby’s hash table.

▼ `struct RHash`

341 struct RHash {

342 struct RBasic basic;

343 struct st_table *tbl;

344 int iter_lev;

345 VALUE ifnone;

346 };

(ruby.h)

It’s a wrapper for `struct st_table`. `st_table` will be detailed in the next chapter “Names and name tables.”

`ifnone` is the value when a key does not have an associated value, its default is `nil`. `iter_lev` is to make the hashtable reentrant (multithread safe).

`struct RFile`

`struct RFile` is a struct for instances of the built-in IO class and its subclasses.

▼ `struct RFile`

348 struct RFile {

349 struct RBasic basic;

350 struct OpenFile *fptr;

351 };

(ruby.h)

▼ `OpenFile`

19 typedef struct OpenFile {

20 FILE *f; /* stdio ptr for read/write */

21 FILE *f2; /* additional ptr for rw pipes */

22 int mode; /* mode flags */

23 int pid; /* child's pid (for pipes) */

24 int lineno; /* number of lines read */

25 char *path; /* pathname for file */

26 void (*finalize) _((struct OpenFile*)); /* finalize proc */

27 } OpenFile;

(rubyio.h)

All members have been transferred in `struct OpenFile`. As there aren’t many instances of `IO` objects, it’s OK to do it like this. The purpose of each member is written in the comments. Basically, it’s a wrapper around C’s `stdio`.

`struct RData`

`struct RData` has a different tenor from what we saw before. It is the struct for implementation of extension libraries.

Of course structs for classes created in extension libraries are necessary, but as the types of these structs depend on the created class, it’s impossible to know their size or struct in advance. That’s why a “struct for managing a pointer to a user defined struct” has been created on `ruby`’s side to manage this. This struct is `struct RData`.

▼ `struct RData`

353 struct RData {

354 struct RBasic basic;

355 void (*dmark) _((void*));

356 void (*dfree) _((void*));

357 void *data;

358 };

(ruby.h)

`data` is a pointer to the user defined struct, `dfree` is the function used to free that user defined struct, and `dmark` is the function to do “mark” of the mark and sweep.

Because explaining `struct RData` is still too complicated, for the time being let’s just look at its representation (figure 8). The detailed explanation of its members will be introduced after we’ll finish chapter 5 “Garbage collection.”