Ruby Hacking Guide

Chapter 19: Threads

Outline

Ruby Interface

Come to think of it, I feel I have not introduced an actual code to use Ruby threads. This is not so special, but here I’ll introduce it just in case.

Thread.fork {

while true

puts 'forked thread'

end

}

while true

puts 'main thread'

end

When executing this program, a lot of `“forked thread”` and `“main thread”` are printed in the properly mixed state.

Of course, other than just creating multiple threads, there are also various ways to control. There’s not the `synchronize` as a reserved word like Java, common primitives such as `Mutex` or `Queue` or `Monitor` are of course available, and the below APIs can be used to control a thread itself.

▼ Thread API

| `Thread.pass` | transfer the execution to any other thread |

| `Thread.kill(th)` | terminates the `th` thread |

| `Thread.exit` | terminates the thread itself |

| `Thread.stop` | temporarily stop the thread itself |

| `Thread#join` | waiting for the thread to finish |

| `Thread#wakeup` | to wake up the temporarily stopped thread |

`ruby` Thread

Threads are supposed to “run all together”, but actually they are running for a little time in turns. To be precise, by making some efforts on a machine of multi CPU, it’s possible that, for instance, two of them are running at the same time. But still, if there are more threads than the number of CPU, they have to run in turns.

In other words, in order to create threads, someone has to switch the threads in somewhere. There are roughly two ways to do it: kernel-level threads and user-level threads. They are respectively, as the names suggest, to create a thread in kernel or at user-level. If it is kernel-level, by making use of multi-CPU, multiple threads can run at the same time.

Then, how about the thread of `ruby`? It is user-level thread. And (Therefore), the number of threads that are runnable at the same time is limited to one.

Is it preemptive?

I’ll describe about the traits of `ruby` threads in more detail. As an alternative point of view of threads, there’s the point that is “is it preemptive?”.

When we say “thread (system) is preemptive”, the threads will automatically be switched without being explicitly switched by its user. Looking this from the opposite direction, the user can’t control the timing of switching threads.

On the other hand, in a non-preemptive thread system, until the user will explicitly say “I can pass the control right to the next thread”, threads will never be switched. Looking this from the opposite direction, when and where there’s the possibility of switching threads is obvious.

This distinction is also for processes, in that case, preemptive is considered as “superior”. For example, if a program had a bug and it entered an infinite loop, the processes would never be able to switch. This means a user program can halt the whole system and is not good. And, switching processes was non-preemptive on Windows 3.1 because its base was MS-DOS, but Windows 95 is preemptive. Thus, the system is more robust. Hence, it is said that Windows 95 is “superior” to 3.1.

Then, how about the `ruby` thread? It is preemptive at Ruby-level, and non-preemptive at C level. In other words, when you are writing C code, you can determine almost certainly the timings of switching threads.

Why is this designed in this way? Threads are indeed convenient, but its user also need to prepare certain minds. It means that it is necessary the code is compatible to the threads. (It must be multi-thread safe). In other words, in order to make it preemptive also in C level, the all C libraries have to be thread safe.

But in reality, there are also a lot of C libraries that are still not thread safe. A lot of efforts were made to ease to write extension libraries, but it would be brown if the number of usable libraries is decreased by requiring thread safety. Therefore, non-preemptive at C level is a reasonable choice for `ruby`.

Management System

We’ve understand `ruby` thread is non-preemptive at C level. It means after it runs for a while, it voluntarily let go of the controlling right. Then, I’d like you to suppose that now a currently being executed thread is about to quit the execution. Who will next receive the control right? But before that, it’s impossible to guess it without knowing how threads are expressed inside `ruby` in the first place. Let’s look at the variables and the data types to manage threads.

▼ the structure to manage threads

864 typedef struct thread * rb_thread_t;

865 static rb_thread_t curr_thread = 0;

866 static rb_thread_t main_thread;

7301 struct thread {

7302 struct thread *next, *prev;

(eval.c)

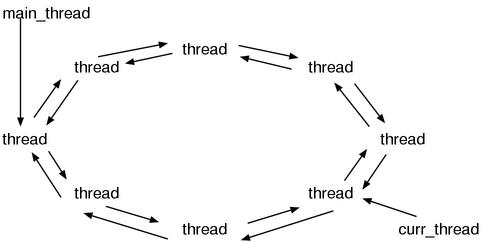

Since `struct thread` is very huge for some reason, this time I narrowed it down to the only important part. It is why there are only the two. These `next` and `prev` are member names, and their types are `rb_thread_t`, thus we can expect `rb_thread_t` is connected by a dual-directional link list. And actually it is not an ordinary dual-directional list, the both ends are connected. It means, it is circular. This is a big point. Adding the static `main_thread` and `curr_thread` variables to it, the whole data structure would look like Figure 1.

Figure 1: the data structures to manage threads

`main_thread` (main thread) means the thread existed at the time when a program started, meaning the “first” thread. `curr_thread` is obviously `current thread`, meaning the thread currently running. The value of `main_thread` will never change while the process is running, but the value of `curr_thread` will change frequently.

In this way, because the list is being a circle, the procedure to chose “the next thread” becomes easy. It can be done by merely following the `next` link. Only by this, we can run all threads equally to some extent.

What does switching threads mean?

By the way, what is a thread in the first place? Or, what makes us to say threads are switched?

These are very difficult questions. Similar to what a program is or what an object is, when asked about what are usually understood by feelings, it’s hard to answer clearly. Especially, “what is the difference between threads and processes?” is a good question.

Still, in a realistic range, we can describe it to some extent. What necessary for threads is the context of executing. As for the context of `ruby`, as we’ve seen by now, it consists of `ruby_frame` and `ruby_scope` and `ruby_class` and so on. And `ruby` allocates the substance of `ruby_frame` on the machine stack, and there are also the stack space used by extension libraries, therefore the machine stack is also necessary as a context of a Ruby program. And finally, the CPU registers are indispensable. These various contexts are the elements to enable threads, and switching them means switching threads. Or, it is called “context-switch”.

The way of context-switching

The rest talk is how to switch contexts. `ruby_scope` and `ruby_class` are easy to replace: allocate spaces for them somewhere such as the heap and set them aside one by one. For the CPU registers, we can make it because we can save and write back them by using `setjmp()`. The spaces for both purposes are respectively prepared in `rb_thread_t`.

▼ `struct thread` (partial)

7301 struct thread {

7302 struct thread *next, *prev;

7303 jmp_buf context;

7315 struct FRAME *frame; /* ruby_frame */

7316 struct SCOPE *scope; /* ruby_scope */

7317 struct RVarmap *dyna_vars; /* ruby_dyna_vars */

7318 struct BLOCK *block; /* ruby_block */

7319 struct iter *iter; /* ruby_iter */

7320 struct tag *tag; /* prot_tag */

7321 VALUE klass; /* ruby_class */

7322 VALUE wrapper; /* ruby_wrapper */

7323 NODE *cref; /* ruby_cref */

7324

7325 int flags; /* scope_vmode / rb_trap_immediate / raised */

7326

7327 NODE *node; /* rb_current_node */

7328

7329 int tracing; /* tracing */

7330 VALUE errinfo; /* $! */

7331 VALUE last_status; /* $? */

7332 VALUE last_line; /* $_ */

7333 VALUE last_match; /* $~ */

7334

7335 int safe; /* ruby_safe_level */

(eval.c)

As shown above, there are the members that seem to correspond to `ruby_frame` and `ruby_scope`. There’s also a `jmp_buf` to save the registers.

Then, the problem is the machine stack. How can we substitute them?

The way which is the most straightforward for the mechanism is directly writing over the pointer to the position (end) of the stack. Usually, it is in the CPU registers. Sometimes it is a specific register, and it is also possible that a general-purpose register is allocated for it. Anyway, it is in somewhere. For convenience, we’ll call it the stack pointer from now on. It is obvious that the different space can be used as the stack by modifying it. But it is also obvious in this way we have to deal with it for each CPU and for each OS, thus it is really hard to serve the potability.

Therefore, `ruby` uses a very violent way to implement the substitution of the machine stack. That is, if we can’t modify the stack pointer, let’s modify the place the stack pointer points to. We know the stack can be directly modified as we’ve seen in the description about the garbage collection, the rest is slightly changing what to do. The place to store the stack properly exists in `struct thread`.

▼ `struct thread` (partial)

7310 int stk_len; /* the stack length */ 7311 int stk_max; /* the size of memory allocated for stk_ptr */ 7312 VALUE*stk_ptr; /* the copy of the stack */ 7313 VALUE*stk_pos; /* the position of the stack */ (eval.c)

How the explanation goes

So far, I’ve talked about various things, but the important points can be summarized to the three:

- When

- To which thread

- How

to switch context. These are also the points of this chapter. Below, I’ll describe them using a section for each of the three points respectively.

Trigger

To begin with, it’s the first point, when to switch threads. In other words, what is the cause of switching threads.

Waiting I/O

For example, when trying to read in something by calling `IO#gets` or `IO#read`, since we can expect it will take a lot of time to read, it’s better to run the other threads in the meantime. In other words, a forcible switch becomes necessary here. Below is the interface of `getc`.

▼ `rb_getc()`

1185 int

1186 rb_getc(f)

1187 FILE *f;

1188 {

1189 int c;

1190

1191 if (!READ_DATA_PENDING(f)) {

1192 rb_thread_wait_fd(fileno(f));

1193 }

1194 TRAP_BEG;

1195 c = getc(f);

1196 TRAP_END;

1197

1198 return c;

1199 }

(io.c)

`READ_DATA_PENDING(f)` is a macro to check if the content of the buffer of the file is still there. If there’s the content of the buffer, it means it can move without any waiting time, thus it would read it immediately. If it was empty, it means it would take some time, thus it would `rb_thread_wait_fd()`. This is an indirect cause of switching threads.

If `rb_thread_wait_fd()` is “indirect”, there also should be a “direct” cause. What is it? Let’s see the inside of `rb_thread_wait_fd()`.

▼ `rb_thread_wait_fd()`

8047 void

8048 rb_thread_wait_fd(fd)

8049 int fd;

8050 {

8051 if (rb_thread_critical) return;

8052 if (curr_thread == curr_thread->next) return;

8053 if (curr_thread->status == THREAD_TO_KILL) return;

8054

8055 curr_thread->status = THREAD_STOPPED;

8056 curr_thread->fd = fd;

8057 curr_thread->wait_for = WAIT_FD;

8058 rb_thread_schedule();

8059 }

(eval.c)

There’s `rb_thread_schedule()` at the last line. This function is the “direct cause”. It is the heart of the implementation of the `ruby` threads, and does select and switch to the next thread.

What makes us understand this function has such role is, in my case, I knew the word “scheduling” of threads beforehand. Even if you didn’t know, because you remembers now, you’ll be able to notice it at the next time.

And, in this case, it does not merely pass the control to the other thread, but it also stops itself. Moreover, it has an explicit deadline that is “by the time when it becomes readable”. Therefore, this request should be told to `rb_thread_schedule()`. This is the part to assign various things to the members of `curr_thread`. The reason to stop is stored in `wait_for`, the information to be used when waking up is stored in `fd`, respectively.

Waiting the other thread

After understanding threads are switched at the timing of `rb_thread_schedule()`, this time, conversely, from the place where `rb_thread_schedule()` appears, we can find the places where threads are switched. Then by scanning, I found it in the function named `rb_thread_join()`.

▼ `rb_thread_join()` (partial)

8227 static int

8228 rb_thread_join(th, limit)

8229 rb_thread_t th;

8230 double limit;

8231 {

8243 curr_thread->status = THREAD_STOPPED;

8244 curr_thread->join = th;

8245 curr_thread->wait_for = WAIT_JOIN;

8246 curr_thread->delay = timeofday() + limit;

8247 if (limit < DELAY_INFTY) curr_thread->wait_for |= WAIT_TIME;

8248 rb_thread_schedule();

(eval.c)

This function is the substance of `Thread#join`, and `Thread#join` is a method to wait until the receiver thread will end. Indeed, since there’s time to wait, running the other threads is economy. Because of this, the second reason to switch is found.

Waiting For Time

Moreover, also in the function named `rb_thread_wait_for()`, `rb_thread_schedule()` was found. This is the substance of (Ruby’s) `sleep` and such.

▼ `rb_thread_wait_for` (simplified)

8080 void

8081 rb_thread_wait_for(time)

8082 struct timeval time;

8083 {

8084 double date;

8124 date = timeofday() +

(double)time.tv_sec + (double)time.tv_usec*1e-6;

8125 curr_thread->status = THREAD_STOPPED;

8126 curr_thread->delay = date;

8127 curr_thread->wait_for = WAIT_TIME;

8128 rb_thread_schedule();

8129 }

(eval.c)

`timeofday()` returns the current time. Because the value of `time` is added to it, `date` indicates the time when the waiting time is over. In other words, this is the order “I’d like to stop until it will be the specific time”.

Switch by expirations

In the above all cases, because some manipulations are done from Ruby level, consequently it causes to switch threads. In other words, by now, the Ruby-level is also non-preemptive. Only by this, if a program was to single-mindedly keep calculating, a particular thread would continue to run eternally. Therefore, we need to let it voluntary dispose the control right after running for a while. Then, how long a thread can run by the time when it will have to stop, is what I’ll talk about next.

`setitimer`

Since it is the same every now and then, I feel like lacking the skill to entertain, but I searched the places where calling `rb_thread_schedule()` further. And this time it was found in the strange place. It is here.

▼ `catch_timer()`

8574 static void

8575 catch_timer(sig)

8576 int sig;

8577 {

8578 #if !defined(POSIX_SIGNAL) && !defined(BSD_SIGNAL)

8579 signal(sig, catch_timer);

8580 #endif

8581 if (!rb_thread_critical) {

8582 if (rb_trap_immediate) {

8583 rb_thread_schedule();

8584 }

8585 else rb_thread_pending = 1;

8586 }

8587 }

(eval.c)

This seems something relating to signals. What is this? I followed the place where this `catch_timer()` function is used, then it was used around here:

▼ `rb_thread_start_0()` (partial)

8620 static VALUE

8621 rb_thread_start_0(fn, arg, th_arg)

8622 VALUE (*fn)();

8623 void *arg;

8624 rb_thread_t th_arg;

8625 {

8632 #if defined(HAVE_SETITIMER)

8633 if (!thread_init) {

8634 #ifdef POSIX_SIGNAL

8635 posix_signal(SIGVTALRM, catch_timer);

8636 #else

8637 signal(SIGVTALRM, catch_timer);

8638 #endif

8639

8640 thread_init = 1;

8641 rb_thread_start_timer();

8642 }

8643 #endif

(eval.c)

This means, `catch_timer` is a signal handler of `SIGVTALRM`.

Here, “what kind of signal `SIGVTALRM` is” becomes the question. This is actually the signal sent when using the system call named `setitimer`. That’s why there’s a check of `HAVE_SETITIMER` just before it. `setitimer` is an abbreviation of “SET Interval TIMER” and a system call to tell OS to send signals with a certain interval.

Then, where is the place calling `setitimer`? It is the `rb_thread_start_timer()`, which is coincidently located at the last of this list.

To sum up all, it becomes the following scenario. `setitimer` is used to send signals with a certain interval. The signals are caught by `catch_timer()`. There, `rb_thread_schedule()` is called and threads are switched. Perfect.

However, signals could occur anytime, if it was based on only what described until here, it means it would also be preemptive at C level. Then, I’d like you to see the code of `catch_timer()` again.

if (rb_trap_immediate) {

rb_thread_schedule();

}

else rb_thread_pending = 1;

There’s a required condition that is doing `rb_thread_schedule()` only when it is `rb_trap_immediate`. This is the point. `rb_trap_immediate` is, as the name suggests, expressing “whether or not immediately process signals”, and it is usually false. It becomes true only while the limited time such as while doing I/O on a single thread. In the source code, it is the part between `TRAP_BEG` and `TRAP_END`.

On the other hand, since `rb_thread_pending` is set when it is false, let’s follow this. This variable is used in the following place.

▼ `CHECK_INTS` − `HAVE_SETITIMER`

73 #if defined(HAVE_SETITIMER) && !defined(__BOW__)

74 EXTERN int rb_thread_pending;

75 # define CHECK_INTS do {\

76 if (!rb_prohibit_interrupt) {\

77 if (rb_trap_pending) rb_trap_exec();\

78 if (rb_thread_pending && !rb_thread_critical)\

79 rb_thread_schedule();\

80 }\

81 } while (0)

(rubysig.h)

This way, inside of `CHECK_INTS`, `rb_thread_pending` is checked and `rb_thread_schedule()` is done. It means, when receiving `SIGVTALRM`, `rb_thread_pending` becomes true, then the thread will be switched at the next time going through `CHECK_INTS`.

This `CHECK_INTS` has appeared at various places by now. For example, `rb_eval()` and `rb_call0()` and `rb_yeild_0`. `CHECK_INTS` would be meaningless if it was not located where the place frequently being passed. Therefore, it is natural to exist in the important functions.

`tick`

We understood the case when there’s `setitimer`. But what if `setitimer` does not exist? Actually, the answer is in `CHECK_INTS`, which we’ve just seen. It is the definition of the `#else` side.

▼ `CHECK_INTS` − `not HAVE_SETITIMER`

84 EXTERN int rb_thread_tick;

85 #define THREAD_TICK 500

86 #define CHECK_INTS do {\

87 if (!rb_prohibit_interrupt) {\

88 if (rb_trap_pending) rb_trap_exec();\

89 if (!rb_thread_critical) {\

90 if (rb_thread_tick-- <= 0) {\

91 rb_thread_tick = THREAD_TICK;\

92 rb_thread_schedule();\

93 }\

94 }\

95 }\

96 } while (0)

(rubysig.h)

Every time going through `CHECK_INTS`, decrement `rb_thread_tick`. When it becomes 0, do `rb_thread_schedule()`. In other words, the mechanism is that the thread will be switched after `THREAD_TICK` (=500) times going through `CHECK_INTS`.

Scheduling

The second point is to which thread to switch. What solely responsible for this decision is `rb_thread_schedule()`.

`rb_thread_schedule()`

The important functions of `ruby` are always huge. This `rb_thread_schedule()` has more than 220 lines. Let’s exhaustively divide it into portions.

▼ `rb_thread_schedule()` (outline)

7819 void

7820 rb_thread_schedule()

7821 {

7822 rb_thread_t next; /* OK */

7823 rb_thread_t th;

7824 rb_thread_t curr;

7825 int found = 0;

7826

7827 fd_set readfds;

7828 fd_set writefds;

7829 fd_set exceptfds;

7830 struct timeval delay_tv, *delay_ptr;

7831 double delay, now; /* OK */

7832 int n, max;

7833 int need_select = 0;

7834 int select_timeout = 0;

7835

7836 rb_thread_pending = 0;

7837 if (curr_thread == curr_thread->next

7838 && curr_thread->status == THREAD_RUNNABLE)

7839 return;

7840

7841 next = 0;

7842 curr = curr_thread; /* starting thread */

7843

7844 while (curr->status == THREAD_KILLED) {

7845 curr = curr->prev;

7846 }

/* ……prepare the variables used at select …… */

/* ……select if necessary …… */

/* ……decide the thread to invoke next …… */

/* ……context-switch …… */

8045 }

(eval.c)

(A) When there’s only one thread, this does not do anything and returns immediately. Therefore, the talks after this can be thought based on the assumption that there are always multiple threads.

(B) Subsequently, the initialization of the variables. We can consider the part until and including the `while` is the initialization. Since `cur` is following `prev`, the last alive thread (`status != THREAD_KILLED`) will be set. It is not “the first” one because there are a lot of loops that “start with the next of `curr` then deal with `curr` and end”.

After that, we can see the sentences about `select`. Since the thread switch of `ruby` is considerably depending on `select`, let’s first study about `select` in advance here.

`select`

`select` is a system call to wait until the preparation for reading or writing a certain file will be completed. Its prototype is this:

int select(int max,

fd_set *readset, fd_set *writeset, fd_set *exceptset,

struct timeval *timeout);

In the variable of type `fd_set`, a set of `fd` that we want to check is stored. The first argument `max` is “(the maximum value of `fd` in `fd_set`) + 1”. The `timeout` is the maximum waiting time of `select`. If `timeout` is `NULL`, it would wait eternally. If `timeout` is 0, without waiting for even just a second, it would only check and return immediately. As for the return value, I’ll talk about it at the moment when using it.

I’ll talk about `fd_set` in detail. `fd_set` can be manipulated by using the below macros:

▼ `fd_set` maipulation

fd_set set; FD_ZERO(&set) /* initialize */ FD_SET(fd, &set) /* add a file descriptor fd to the set */ FD_ISSET(fd, &set) /* true if fd is in the set */

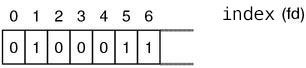

`fd_set` is typically a bit array, and when we want to check n-th file descriptor, the n-th bit is set (Figure 2).

Figure 2: fd_set

I’ll show a simple usage example of `select`.

▼ a usage exmple of `select`

#include <stdio.h>

#include <sys/types.h>

#include <sys/time.h>

#include <unistd.h>

int

main(int argc, char **argv)

{

char *buf[1024];

fd_set readset;

FD_ZERO(&readset); /* initialize readset */

FD_SET(STDIN_FILENO, &readset); /* put stdin into the set */

select(STDIN_FILENO + 1, &readset, NULL, NULL, NULL);

read(STDIN_FILENO, buf, 1024); /* success without delay */

exit(0);

}

This code assume the system call is always success, thus there are not any error checks at all. I’d like you to see only the flow that is `FD_ZERO` → `FD_SET` → `select`. Since here the fifth argument `timeout` of `select` is `NULL`, this `select` call waits eternally for reading `stdin`. And since this `select` is completed, the next `read` does not have to wait to read at all. By putting `print` in the middle, you will get further understandings about its behavior. And a little more detailed example code is put in the attached CD-ROM {see also `doc/select.html`}.

Preparations for `select`

Now, we’ll go back to the code of `rb_thread_schedule()`. Since this code branches based on the reason why threads are waiting. I’ll show the content in shortened form.

▼ `rb_thread_schedule()` − preparations for `select`

7848 again:

/* initialize the variables relating to select */

7849 max = -1;

7850 FD_ZERO(&readfds);

7851 FD_ZERO(&writefds);

7852 FD_ZERO(&exceptfds);

7853 delay = DELAY_INFTY;

7854 now = -1.0;

7855

7856 FOREACH_THREAD_FROM(curr, th) {

7857 if (!found && th->status <= THREAD_RUNNABLE) {

7858 found = 1;

7859 }

7860 if (th->status != THREAD_STOPPED) continue;

7861 if (th->wait_for & WAIT_JOIN) {

/* ……join wait…… */

7866 }

7867 if (th->wait_for & WAIT_FD) {

/* ……I/O wait…… */

7871 }

7872 if (th->wait_for & WAIT_SELECT) {

/* ……select wait…… */

7882 }

7883 if (th->wait_for & WAIT_TIME) {

/* ……time wait…… */

7899 }

7900 }

7901 END_FOREACH_FROM(curr, th);

(eval.c)

Whether it is supposed to be or not, what stand out are the macros named `FOREACH`-some. These two are defined as follows:

▼ `FOREACH_THREAD_FROM`

7360 #define FOREACH_THREAD_FROM(f,x) x = f; do { x = x->next;

7361 #define END_FOREACH_FROM(f,x) } while (x != f)

(eval.c)

Let’s extract them for better understandability.

th = curr;

do {

th = th->next;

{

.....

}

} while (th != curr);

This means: follow the circular list of threads from the next of `curr` and process `curr` at last and end, and meanwhile the `th` variable is used. This makes me think about the Ruby’s iterators … is this my too much imagination?

Here, we’ll go back to the subsequence of the code, it uses this a bit strange loop and checks if there’s any thread which needs `select`. As we’ve seen previously, since `select` can wait for reading/writing/exception/time all at once, you can probably understand I/O waits and time waits can be centralized by single `select`. And though I didn’t describe about it in the previous section, `select` waits are also possible. There’s also a method named `IO.select` in the Ruby’s library, and you can use `rb_thread_select()` at C level. Therefore, we need to execute that `select` at the same time. By merging `fd_set`, multiple `select` can be done at once.

The rest is only `join` wait. As for its code, let’s see it just in case.

▼ `rb_thread_schedule()` − `select` preparation − `join` wait

7861 if (th->wait_for & WAIT_JOIN) {

7862 if (rb_thread_dead(th->join)) {

7863 th->status = THREAD_RUNNABLE;

7864 found = 1;

7865 }

7866 }

(eval.c)

The meaning of `rb_thread_dead()` is obvious because of its name. It determines whether or not the thread of the argument has finished.

Calling `select`

By now, we’ve figured out whether `select` is necessary or not, and if it is necessary, its `fd_set` has already prepared. Even if there’s a immediately invocable thread (`THREAD_RUNNABLE`), we need to call `select` beforehand. It’s possible that there’s actually a thread that it has already been while since its I/O wait finished and has the higher priority. But in that case, tell `select` to immediately return and let it only check if I/O was completed.

▼ `rb_thread_schedule()` − `select`

7904 if (need_select) {

7905 /* convert delay into timeval */

7906 /* if theres immediately invocable threads, do only I/O checks */

7907 if (found) {

7908 delay_tv.tv_sec = 0;

7909 delay_tv.tv_usec = 0;

7910 delay_ptr = &delay_tv;

7911 }

7912 else if (delay == DELAY_INFTY) {

7913 delay_ptr = 0;

7914 }

7915 else {

7916 delay_tv.tv_sec = delay;

7917 delay_tv.tv_usec = (delay - (double)delay_tv.tv_sec)*1e6;

7918 delay_ptr = &delay_tv;

7919 }

7920

7921 n = select(max+1, &readfds, &writefds, &exceptfds, delay_ptr);

7922 if (n < 0) {

/* …… being cut in by signal or something …… */

7944 }

7945 if (select_timeout && n == 0) {

/* …… timeout …… */

7960 }

7961 if (n > 0) {

/* …… properly finished …… */

7989 }

7990 /* In a somewhere thread, its I/O wait has finished.

7991 roll the loop again to detect the thread */

7992 if (!found && delay != DELAY_INFTY)

7993 goto again;

7994 }

(eval.c)

The first half of the block is as written in the comment. Since `delay` is the `usec` until the any thread will be next invocable, it is converted into `timeval` form.

In the last half, it actually calls `select` and branches based on its result. Since this code is long, I divided it again. When being cut in by a signal, it either goes back to the beginning then processes again or becomes an error. What are meaningful are the rest two.

Timeout

When `select` is timeout, a thread of time wait or `select` wait may become invocable. Check about it and search runnable threads. If it is found, set `THREAD_RUNNABLE` to it.

Completing normally

If `select` is normally completed, it means either the preparation for I/O is completed or `select` wait ends. Search the threads that are no longer waiting by checking `fd_set`. If it is found, set `THREAD_RUNNABLE` to it.

Decide the next thread

Taking all the information into considerations, eventually decide the next thread to invoke. Since all what was invocable and all what had finished waiting and so on became `RUNNABLE`, you can arbitrary pick up one of them.

▼ `rb_thread_schedule()` − decide the next thread

7996 FOREACH_THREAD_FROM(curr, th) {

7997 if (th->status == THREAD_TO_KILL) { /*(A)*/

7998 next = th;

7999 break;

8000 }

8001 if (th->status == THREAD_RUNNABLE && th->stk_ptr) {

8002 if (!next || next->priority < th->priority) /*(B)*/

8003 next = th;

8004 }

8005 }

8006 END_FOREACH_FROM(curr, th);

(eval.c)

(A) if there’s a thread that is about to finish, give it the high priority and let it finish.

(B) find out what seems runnable. However it seems to consider the value of `priority`. This member can also be modified from Ruby level by using `Tread#priority Thread#priority=`. `ruby` itself does not especially modify it.

If these are done but the next thread could not be found, in other words if the `next` was not set, what happen? Since `select` has already been done, at least one of threads of time wait or I/O wait should have finished waiting. If it was missing, the rest is only the waits for the other threads, and moreover there’s no runnable threads, thus this wait will never end. This is a dead lock.

Of course, for the other reasons, a dead lock can happen, but generally it’s very hard to detect a dead lock. Especially in the case of `ruby`, `Mutex` and such are implemented at Ruby level, the perfect detection is nearly impossible.

Switching Threads

The next thread to invoke has been determined. I/O and `select` checks has also been done. The rest is transferring the control to the target thread. However, for the last of `rb_thread_schedule()` and the code to switch threads, I’ll start a new section.

Context Switch

The last third point is thread-switch, and it is context-switch. This is the most interesting part of threads of `ruby`.

The Base Line

Then we’ll start with the tail of `rb_thread_schedule()`. Since the story of this section is very complex, I’ll go with a significantly simplified version.

▼ `rb_thread_schedule()` (context switch)

if (THREAD_SAVE_CONTEXT(curr)) {

return;

}

rb_thread_restore_context(next, RESTORE_NORMAL);

As for the part of `THREAD_SAVE_CONTEXT()`, we need to extract the content at several places in order to understand.

▼ `THREAD_SAVE_CONTEXT()`

7619 #define THREAD_SAVE_CONTEXT(th) \

7620 (rb_thread_save_context(th),thread_switch(setjmp((th)->context)))

7587 static int

7588 thread_switch(n)

7589 int n;

7590 {

7591 switch (n) {

7592 case 0:

7593 return 0;

7594 case RESTORE_FATAL:

7595 JUMP_TAG(TAG_FATAL);

7596 break;

7597 case RESTORE_INTERRUPT:

7598 rb_interrupt();

7599 break;

/* …… process various abnormal things …… */

7612 case RESTORE_NORMAL:

7613 default:

7614 break;

7615 }

7616 return 1;

7617 }

(eval.c)

If I merge the three then extract it, here is the result:

rb_thread_save_context(curr);

switch (setjmp(curr->context)) {

case 0:

break;

case RESTORE_FATAL:

....

case RESTORE_INTERRUPT:

....

/* ……process abnormals…… */

case RESTORE_NORMAL:

default:

return;

}

rb_thread_restore_context(next, RESTORE_NORMAL);

At both of the return value of `setjmp()` and `rb_thread_restore_context()`, `RESTORE_NORMAL` appears, this is clearly suspicious. Since it does `longjmp()` in `rb_thread_restore_context()`, we can expect the correspondence between `setjmp()` and `longjmp()`. And if we will imagine the meaning also from the function names,

save the context of the current thread setjmp restore the context of the next thread longjmp

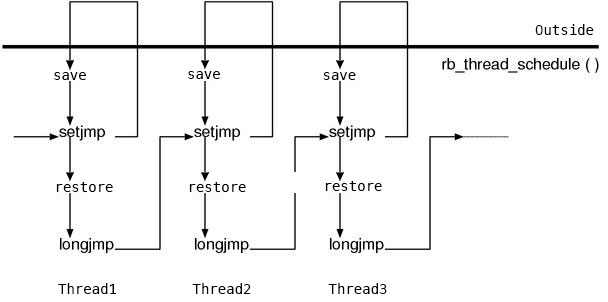

The rough main flow would probably look like this. However what we have to be careful about here is, this pair of `setjmp()` and `longjmp()` is not completed in this thread. `setjmp()` is used to save the context of this thread, `longjmp()` is used to restore the context of the next thread. In other words, there’s a chain of `setjmp`/`longjmp()` as follows. (Figure 3)

Figure 3: the backstitch by chaining of `setjmp`

We can restore around the CPU registers with `setjmp()`/`longjmp()`, so the remaining context is the Ruby stacks in addition to the machine stack. `rb_thread_save_context()` is to save it, and `rb_thread_restore_context()` is to restore it. Let’s look at each of them in sequential order.

`rb_thread_save_context()`

Now, we’ll start with `rb_thread_save_context()`, which saves a context.

▼ `rb_thread_save_context()` (simplified)

7539 static void

7540 rb_thread_save_context(th)

7541 rb_thread_t th;

7542 {

7543 VALUE *pos;

7544 int len;

7545 static VALUE tval;

7546

7547 len = ruby_stack_length(&pos);

7548 th->stk_len = 0;

7549 th->stk_pos = (rb_gc_stack_start<pos)?rb_gc_stack_start

7550 :rb_gc_stack_start - len;

7551 if (len > th->stk_max) {

7552 REALLOC_N(th->stk_ptr, VALUE, len);

7553 th->stk_max = len;

7554 }

7555 th->stk_len = len;

7556 FLUSH_REGISTER_WINDOWS;

7557 MEMCPY(th->stk_ptr, th->stk_pos, VALUE, th->stk_len);

/* …………omission………… */

}

(eval.c)

The last half is just keep assigning the global variables such as `ruby_scope` into `th`, so it is omitted because it is not interesting. The rest, in the part shown above, it attempts to copy the entire machine stack into the place where `th→stk_ptr` points to.

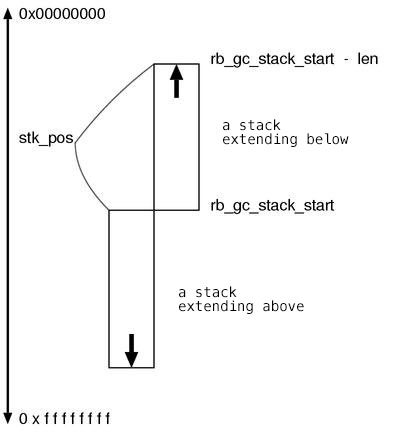

First, it is `ruby_stack_length()` which writes the head address of the stack into the parameter `pos` and returns its length. The range of the stack is determined by using this value and the address of the bottom-end side is set to `th→stk_ptr`. We can see some branches, it is because both a stack extending higher and a stack extending lower are possible. (Figure 4)

Fig.4: a stack extending above and a stack extending below

After that, the rest is allocating a memory in where `th→stkptr` points to and copying the stack: allocate the memory whose size is `th→stk_max` then copy the stack by the `len` length.

`FLUSH_REGISTER_WINDOWS` was described in Chapter 5: Garbage collection, so its explanation might no longer be necessary. This is a macro (whose substance is written in Assembler) to write down the cache of the stack space to the memory. It must be called when the target is the entire stack.

`rb_thread_restore_context()`

And finally, it is `rb_thread_restore_context()`, which is the function to restore a thread.

▼ `rb_thread_restore_context()`

7635 static void

7636 rb_thread_restore_context(th, exit)

7637 rb_thread_t th;

7638 int exit;

7639 {

7640 VALUE v;

7641 static rb_thread_t tmp;

7642 static int ex;

7643 static VALUE tval;

7644

7645 if (!th->stk_ptr) rb_bug("unsaved context");

7646

7647 if (&v < rb_gc_stack_start) {

7648 /* the machine stack extending lower */

7649 if (&v > th->stk_pos) stack_extend(th, exit);

7650 }

7651 else {

7652 /* the machine stack extending higher */

7653 if (&v < th->stk_pos + th->stk_len) stack_extend(th, exit);

7654 }

/* omission …… back the global variables */

7677 tmp = th;

7678 ex = exit;

7679 FLUSH_REGISTER_WINDOWS;

7680 MEMCPY(tmp->stk_pos, tmp->stk_ptr, VALUE, tmp->stk_len);

7681

7682 tval = rb_lastline_get();

7683 rb_lastline_set(tmp->last_line);

7684 tmp->last_line = tval;

7685 tval = rb_backref_get();

7686 rb_backref_set(tmp->last_match);

7687 tmp->last_match = tval;

7688

7689 longjmp(tmp->context, ex);

7690 }

(eval.c)

The `th` parameter is the target to give the execution back. `MEMCPY` in the last half are at the heart. The closer `MEMCPY`.

Nevertheless, there are `rb_lastline_set()` and `rb_backref_set()`. They are the restorations of `$_` and `$~`. Since these two variables are not only local variables but also thread local variables, even if it is only a single local variable slot, there are its as many slots as the number of threads. This must be here because the place actually being written back is the stack. Because they are local variables, their slot spaces are allocated with `alloca()`.

That’s it for the basics. But if we merely write the stack back, in the case when the stack of the current thread is shorter than the stack of the thread to switch to, the stack frame of the very currently executing function (it is `rb_thread_restore_context`) would be overwritten. It means the content of the `th` parameter will be destroyed. Therefore, in order to prevent this from occurring, we first need to extend the stack. This is done by the `stack_extend()` in the first half.

▼ `stack_extend()`

7624 static void

7625 stack_extend(th, exit)

7626 rb_thread_t th;

7627 int exit;

7628 {

7629 VALUE space[1024];

7630

7631 memset(space, 0, 1); /* prevent array from optimization */

7632 rb_thread_restore_context(th, exit);

7633 }

(eval.c)

By allocating a local variable (which will be put at the machine stack space) whose size is 1K, forcibly extend the stack. However, though this is a matter of course, doing `return` from `stack_extend()` means the extended stack will shrink immediately. This is why `rb_thread_restore_context()` is called again immediately in the place.

By the way, the completion of the task of `rb_thread_restore_context()` means it has reached the call of `longjmp()`, and once it is called it will never return back. Obviously, the call of `stack_extend()` will also never return. Therefore, `rb_thread_restore_context()` does not have to think about such as possible procedures after returning from `stack_extend()`.

Issues

This is the implementation of the `ruby` thread switch. We can’t think it is lightweight. Plenty of `malloc() realloc()` and plenty of `memcpy()` and doing `setjmp() longjmp()` then furthermore calling functions to extend the stack. There’s no problem to express “It is deadly heavy”. But instead, there’s not any system call depending on a particular OS, and there are just a few assembly only for the register windows of Sparc. Indeed, this seems to be highly portable.

There’s another problem. It is, because the stacks of all threads are allocated to the same address, there’s the possibility that the code using the pointer to the stack space is not runnable. Actually, Tcl/Tk excellently matches this situation, in order to bypass, Ruby’s Tcl/Tk interface reluctantly choses to access only from the main thread.

Of course, this does not go along with native threads. It would be necessary to restrict `ruby` threads to run only on a particular native thread in order to let them work properly. In UNIX, there are still a few libraries that use a lot of threads. But in Win32, because threads are running every now and then, we need to be careful about it.